A technical deep-dive into an experimental project that boots an IBM PC from a vinyl record, exploring the intersection of vintage computing hardware, analog audio recording, and bootloaders.

The standard boot sequence for most computers is a predictable affair: BIOS checks the hard drive, then the SSD, perhaps a network connection, and finally falls back to a USB drive or DVD. It's efficient, reliable, and utterly mundane. For a tinkerer, this predictability is a challenge. What if the boot process itself could be a statement—something that bridges the gap between the digital and the analog? This is the premise behind a fascinating experiment: booting an IBM PC directly from a vinyl record.

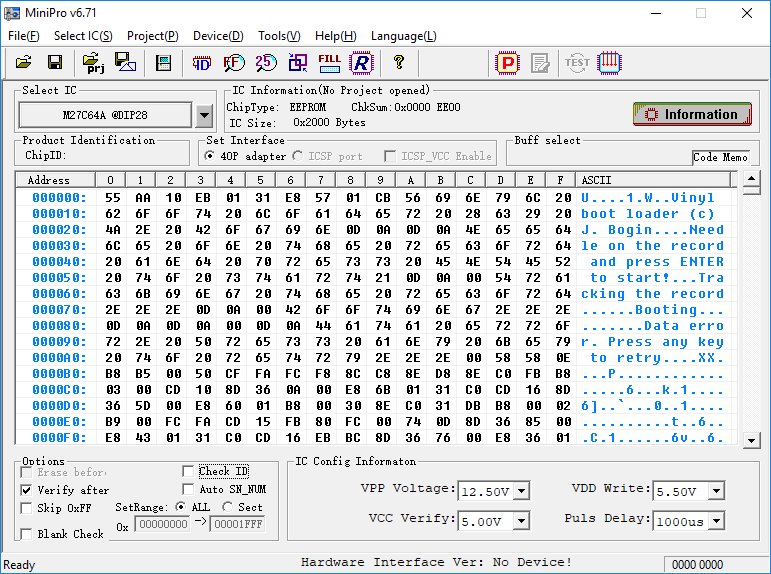

The project, documented by BOGIN, JR., isn't a simple prank. It's a technically rigorous endeavor that repurposes the long-dormant "cassette interface" on an IBM PC (specifically the 5150 model). This interface, a relic from an era when audio cassettes were a legitimate data storage medium, was rarely used and is often forgotten. The experiment's core is a custom bootloader, burned onto a ROM chip and installed in the PC's BIOS expansion socket. This ROM code is designed to be invoked only when all conventional boot options—floppy disk, hard drive—have failed, turning the cassette interface into a last-resort boot device.

The Technical Architecture: From Audio to RAM

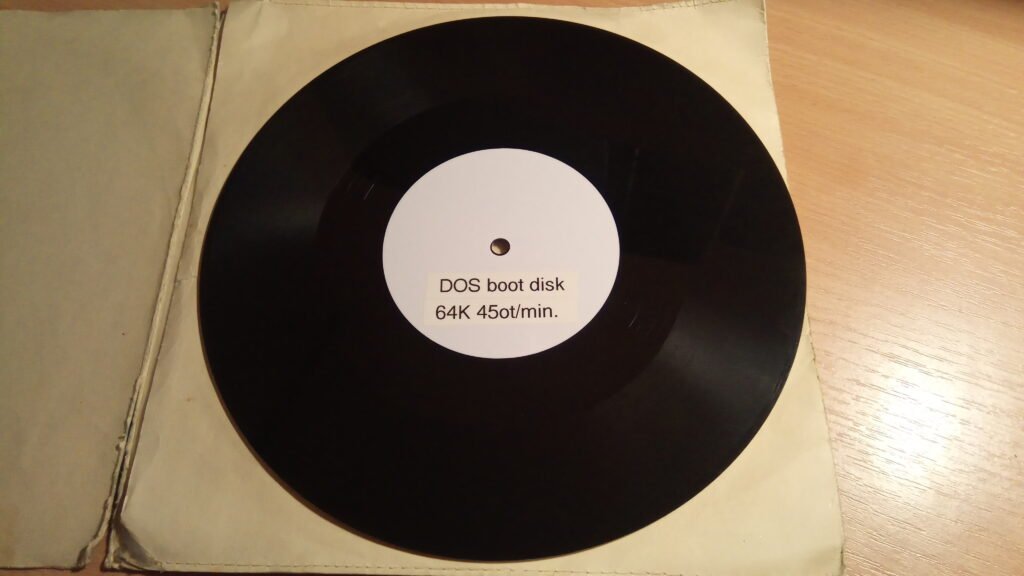

The process begins with a digital disk image: a 64KB FreeDOS boot disk. This isn't a full operating system; it's a minimal, modified kernel, a stripped-down COMMAND.COM, and a patched version of INTERLNK for file transfers. The challenge is to encode this 64KB of data into an analog audio signal that the PC's cassette interface can read.

The PC's cassette interface is surprisingly simple. For output, it uses the PC speaker's timer channel 2. For input, it relies on the 8255A-5 PPI (Programmable Peripheral Interface), specifically port C, channel 4 (I/O port 62h, bit 4). The BIOS's INT 15h routines handle the software modulation and demodulation of the data stream. The project leverages existing tools, specifically a utility called 5150CAXX, to convert the binary disk image into an audio signal compliant with the IBM cassette tape protocol. This audio signal is then sent directly to a record-cutting lathe, etching the data into the grooves of a 10-inch vinyl record.

Playback introduces the complexities of analog media. Vinyl records are mastered with an RIAA equalization curve—a standard bass boost/treble cut that is reversed by a phono preamp during playback. However, this reversal isn't perfect, especially for a non-musical, high-frequency data signal. The experiment required careful signal correction. Using a vintage Harman & Kardon 6300 amplifier with an integrated MM phono preamp, the author had to manually adjust the equalization: treble was reduced by 10dB at 10kHz, bass was increased by approximately 6dB at 50Hz, and the output volume was carefully set to 0.7 volts peak to avoid distortion. Any phase or loudness correction features on the amplifier had to be disabled.

Tolerance and Constraints of Analog Booting

The cassette modem interface is remarkably forgiving of the signal's origin—it doesn't care if the data comes from a magnetic tape or a vinyl groove. However, the physical medium imposes strict constraints. The recording must be pristine; loud pops, crackles, or dropouts will interrupt the data stream and cause the boot to fail. The system does, however, tolerate some imperfections. A small amount of "wow" (speed variation) is acceptable, and the playback speed can deviate by 2-3% without breaking the data stream. This tolerance is a testament to the robustness of the original IBM cassette interface design, which was built for the less-than-perfect conditions of home audio recording.

The final piece of the puzzle is the bootloader itself. Designed for a 2364 EPROM chip (a 2764 can be used with an adapter), the binary is available for download. It's configured for an IBM 5150 with a monochrome display and at least 512KB of RAM—a setup that mirrors the author's own hardware, a coincidence that speaks to the project's grounded, practical nature.

Why This Matters: Beyond the Novelty

While undeniably quirky, this project serves as a powerful demonstration of low-level system understanding. It forces a confrontation with the layers of abstraction that modern computing has built over hardware. To make this work, one must understand:

- BIOS Boot Sequence: How the system prioritizes boot devices and where custom code can be injected.

- Hardware Interfaces: The direct manipulation of legacy hardware like the PPI and timer channels.

- Data Encoding/Decoding: The principles of modulation and demodulation, and how they translate digital data into analog waveforms.

- Analog Signal Processing: The real-world effects of equalization curves, amplifier stages, and physical media imperfections on a digital data stream.

It also highlights the evolution of storage. We've moved from storing data on vinyl (a concept explored in the 1960s with projects like the "Miniwac" computer) to magnetic tape, floppy disks, hard drives, and now solid-state storage. This experiment is a tangible link to that history, a reminder that data has always been a physical phenomenon, whether encoded in magnetic domains, pits on a disc, or grooves in a record.

For those interested in the technical details, the bootloader binary and the original disk image are accessible through the author's documentation. It’s a niche project, but one that offers a unique perspective on the foundations of computing—a perspective that is often lost in the seamless, abstracted world of modern technology.

Relevant Resources:

- Bootloader binary for 2364 EPROM

- BootLPT/86 article with disk image

- 5150CAXX utility for audio signal generation

- IBM PC Cassette Interface Technical Reference (External reference for deeper technical understanding)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion