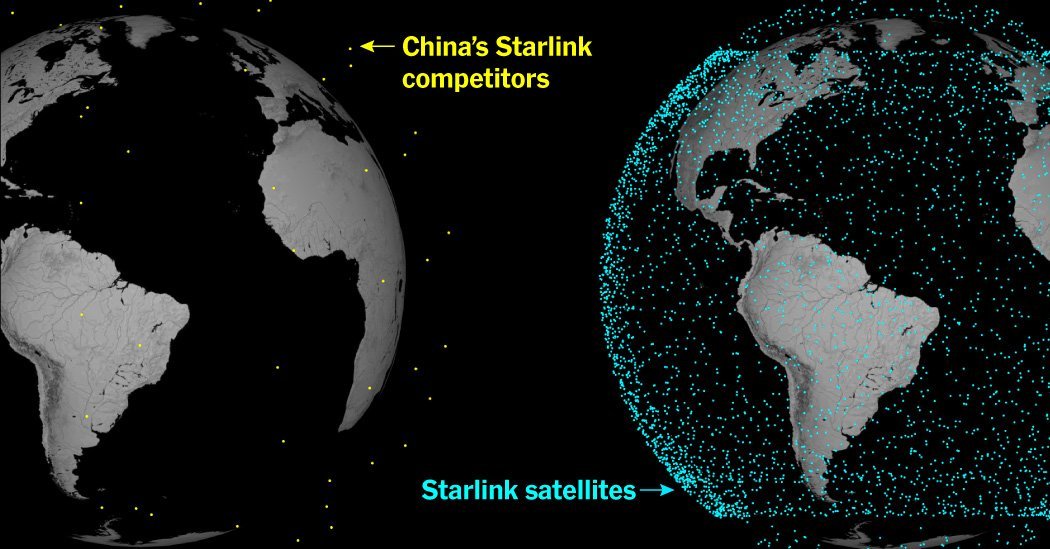

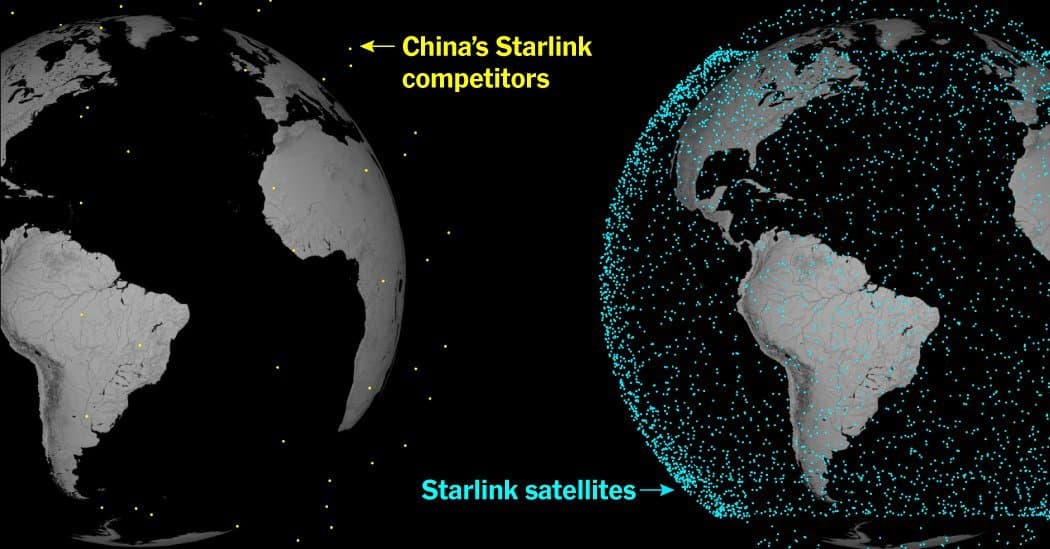

China's plans to rival SpaceX's Starlink constellation with its own massive satellite networks are faltering, deploying less than 1% of their planned 27,000 satellites. The critical bottleneck is China's inability to match SpaceX's reusable Falcon 9 rocket technology, a key factor enabling rapid, cost-effective launches. This delay highlights a significant technological gap with profound implications for global communications infrastructure and military strategy.

The race for supremacy in low Earth orbit (LEO) is intensifying, with over 11,000 satellites currently circling the planet, providing critical internet, navigation, and surveillance capabilities. Yet, this burgeoning market is dominated by a single player: SpaceX’s Starlink network, boasting approximately 8,000 operational satellites. China, aiming to challenge this dominance with ambitious plans for nearly 27,000 satellites across its Qianfan and Guowang megaconstellations, finds itself struggling to get off the ground. Currently, Chinese entities have deployed a mere 120 satellites – less than 1% of their stated goals – revealing a stark technological and operational gap.

The Stakes in Low Earth Orbit

LEO satellites, operating within 1,200 miles of Earth, are increasingly vital infrastructure. They promise seamless connectivity for future technologies like autonomous vehicles and advanced drone operations, and are crucial for modern military surveillance and communications. China views SpaceX's Starlink, already integral to Ukraine's defense communications and drone warfare capabilities, as a direct military threat intertwined with U.S. defense interests. Pentagon contracts for espionage and missile-tracking satellites further cement this perception.

The Falcon 9 Advantage: Reusability is Key

China's unexpectedly slow progress stems primarily from a critical engineering hurdle: the lack of a reliable, reusable rocket launcher. While Chinese companies like Shanghai Spacesail Technologies (Qianfan) and the entity behind Guowang rely on single-use rockets – components of which become space debris or fall back to Earth – SpaceX has revolutionized access to space.

The Falcon 9's first stage returns intact, landing vertically and ready for rapid refurbishment and relaunch. This reusability drastically cuts costs and enables an unprecedented launch cadence. "The question is not just recovering them," explains Dr. Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics tracking space objects, "but recovering them in a good enough state to launch them again."

SpaceX's Falcon 9, a partially reusable rocket, is a cornerstone of its launch dominance. Credit: Steve Nesius/Reuters

SpaceX's Falcon 9, a partially reusable rocket, is a cornerstone of its launch dominance. Credit: Steve Nesius/Reuters

China's Rocket Struggles

Chinese efforts to replicate this capability have stumbled:

- Long March 8: Initially envisioned as reusable, this government-funded model had its reusability plans abandoned by its developer, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology. An improved version, the Long March 8R, remains a future prospect.

- Zhuque-3 (Landspace): This private Chinese rocket has shown promise with liftoff-and-recovery tests, including a 45-second engine firing in June 2025.

- Tianlong-3 (Space Pioneer): Suffered a major setback when a test vehicle took off unexpectedly and exploded in 2024.

"They have to work out the kinks," notes Andrew Jones, a journalist specializing in tracking Chinese space launches. While a breakthrough could come soon, achieving the reliable, rapid launch cadence mastered by SpaceX will take significant time and testing.

Operational Setbacks and Geopolitical Maneuvering

Beyond rocket challenges, operational issues plague China's nascent constellations. Qianfan's deployment of 90 satellites is well short of its 650-satellite target for 2025. Worse, Dr. McDowell estimates 13 of those satellites failed to reach correct orbit and are likely non-functional. Guowang, with a staggering planned fleet of 13,000, has only 34 in orbit.

Despite these setbacks, Chinese firms aggressively market their services, capitalizing on geopolitical unease with U.S. dominance. Shanghai Spacesail claims negotiations with 30 countries, securing deals in Brazil (amid a Starlink legal dispute), Thailand, Malaysia, and Kazakhstan. Satellite internet is becoming "an important feature of economic diplomacy," observes João Falcão Serra of the European Space Policy Institute, where choosing a provider signals geopolitical alignment.

A Chinese Long March 8 rocket launch. Credit: Xiaoxu/Xinhua, via Getty Images

A Chinese Long March 8 rocket launch. Credit: Xiaoxu/Xinhua, via Getty Images

The Crunch of Frequency Rights and Future Outlook

Time is a critical factor. International Telecommunication Union (ITU) rules mandate that constellations must launch half their planned satellites within five years of securing frequencies and complete deployment within seven years. Chinese megaconstellations are already behind schedule, risking the potential loss of their allocated radio frequencies and forcing downsizing.

While Chinese launch activity is accelerating (over 30 launches in H1 2025, deploying ~150 objects), the sheer scale needed for their megaconstellations demands a quantum leap – likely dependent on finally achieving reliable rocket reusability. Satellite launches in China often surge in the second half of the year, offering a potential, though challenging, path to catch up.

The current landscape underscores SpaceX's formidable lead, built on the Falcon 9's disruptive technology. China's ambition is clear, fueled by national security concerns and President Xi Jinping's declaration of a "space dream." However, the path to realizing that dream hinges on solving the rocket equation that SpaceX mastered years ago. As Dr. McDowell observes, the next year or two could signal whether the era of Starlink's overwhelming dominance begins to give way to a more competitive LEO environment, or if the technological gap widens further.

Source: Analysis based on original reporting by The New York Times (July 23, 2025), Celestrak, and Space-Track.org data. Additional context from expert commentary.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion