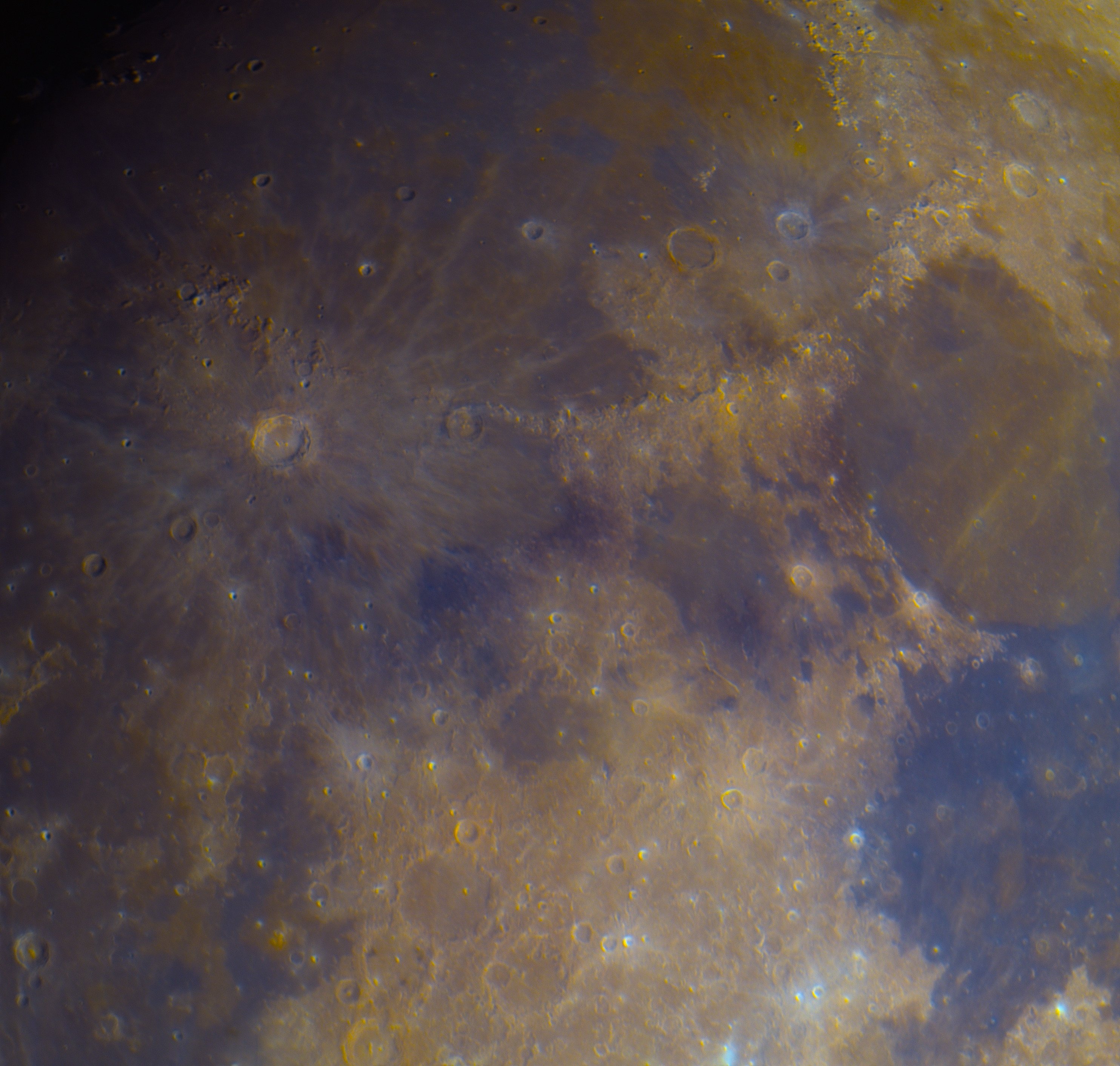

A deep dive into processing a high-resolution moon image to reveal subtle mineral variations, exploring the equipment, techniques, and scientific context behind the 'Mineral Moon' effect.

The image you see above isn't just another pretty picture of the moon. It's a processed stack of thousands of frames, captured through a Celestron C9.25 EdgeHD telescope and an ASI533 MC camera, then processed to reveal subtle color differences in the lunar surface that hint at the moon's geological history. This is what we call a "Mineral Moon"—a technique that pushes the limits of both equipment and processing to show the faint color signatures of different rock compositions.

The Equipment Setup

The foundation of this image is a serious amateur setup:

- Telescope: Celestron C9.25 EdgeHD (9.25" aperture, f/10 focal ratio)

- Camera: ZWO ASI533 MC (IMX533 sensor, one-shot color)

- Mount: Sky-Watcher EQ6-R Pro (equatorial mount with precise tracking)

- Capture: 30 seconds of video at 1ms exposures (30,000 frames)

The C9.25 EdgeHD is a premium Schmidt-Cassegrain design with excellent correction across the field. The 9.25" aperture provides enough light-gathering power to resolve details down to about 0.5 arcseconds under good seeing conditions. The ASI533 MC uses Sony's IMX533 sensor—a 9MP CMOS with excellent quantum efficiency (around 70% peak) and low read noise, making it ideal for planetary and lunar imaging where we're pushing exposure times to the limit.

The EQ6-R mount is crucial here. With a payload capacity of 44 lbs, it can handle this setup with plenty of headroom. More importantly, its periodic error correction (PEC) and precise tracking allow for long-duration video captures without field rotation or significant drift. For lunar imaging, we're typically working at focal lengths around 2350mm (C9.25 at f/10), which means even tiny tracking errors become visible as motion blur.

The Capture Process

Lunar imaging is fundamentally different from deep-sky astrophotography. The moon is bright—so bright that we can use extremely short exposures. The 1ms frames here are typical for planetary/lunar work. At 1ms, we're essentially freezing atmospheric turbulence ("seeing") to capture moments of clarity. The 30,000 frames give us a massive dataset to work with.

The key is that we're not trying to capture a single perfect frame. Instead, we're capturing thousands of "lucky" frames where the atmosphere momentarily stabilizes. The best frames (typically 1-5% of the total) are then stacked to improve signal-to-noise ratio and reveal details that would be lost in a single exposure.

Processing: From Raw Data to Mineral Map

The raw data is a stack of TIFF files—lossless, 16-bit per channel. The processing pipeline involves several stages:

Frame Selection: Using software like AutoStakkert! or RegiStax, we analyze each frame for sharpness and select the top percentage. The ASI533's high frame rate (around 20 fps at full resolution) makes this feasible.

Stacking: The selected frames are aligned and stacked. This averaging process reduces random noise while preserving high-frequency detail. The result is a single, high-SNR TIFF file.

Color Processing: This is where the "Mineral Moon" effect emerges. The moon's surface is actually quite monochromatic in natural light—mostly shades of gray. However, subtle color variations exist due to differences in mineral composition:

- Titanium-rich regions (like the maria) reflect slightly bluish light

- Iron-rich regions (like the highlands) reflect more yellowish light

- The ratio of Fe/Ti (iron to titanium) creates these subtle color signatures

In a typical lunar image, these colors are invisible because:

- The human eye's dynamic range is limited

- Camera sensors are calibrated for "neutral" white balance

- The color differences are extremely subtle (often less than 1% in RGB values)

Saturation Enhancement: The "cranked up" saturation mentioned in the original post is a deliberate artistic choice. By pushing the color saturation in post-processing, we amplify these subtle differences to make them visible. This is similar to how infrared photography reveals hidden patterns in vegetation.

However, there's a scientific basis here. The colors aren't arbitrary—they correlate with known geological features. The blueish tint often appears in the maria (ancient volcanic flows), while the yellowish tint is more common in the highlands (older, more cratered terrain).

The Science Behind the Colors

The moon's surface is primarily composed of basalt (in the maria) and anorthosite (in the highlands). These rocks have different mineral compositions:

- Basalt: Rich in iron and magnesium silicates, with some titanium oxides. The titanium content can vary from 1-15% by weight in different maria regions.

- Anorthosite: Primarily calcium aluminum silicates (plagioclase feldspar), with lower iron and titanium content.

The color differences arise from how these minerals reflect light. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) has a slightly higher reflectance in the blue wavelengths compared to iron oxides (FeO). When we process the image with enhanced saturation, these subtle spectral differences become visible as color variations.

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has mapped these compositions in detail. The Mineral Moon technique essentially creates a visual approximation of these compositional maps using ground-based imaging.

Why This Matters for Amateur Astronomy

This technique represents the intersection of accessible technology and scientific observation. A decade ago, capturing 30,000 frames at 1ms exposures would have required specialized equipment costing tens of thousands of dollars. Today, a setup like this (telescope, camera, mount) can be assembled for under $5,000—still significant, but within reach for serious amateurs.

More importantly, it demonstrates how processing techniques can extract scientific information from what appears to be a simple photograph. The same principles apply to:

- Planetary imaging: Revealing cloud bands on Jupiter or surface features on Mars

- Deep-sky narrowband imaging: Using filters to isolate specific emission lines (Hα, OIII, SII)

- Solar imaging: Showing sunspot structure and prominence detail

Practical Recommendations

If you want to try this yourself:

Start with the moon: It's bright, forgiving, and doesn't require long exposures. A 6-8" telescope and a planetary camera (like the ZWO ASI290MM) can produce excellent results.

Focus on seeing conditions: Lunar imaging is seeing-limited. Use tools like AstroPlanner or Clear Outside to check atmospheric stability. The best results often come in the early morning when the atmosphere is most stable.

Process with intention: Don't just crank saturation blindly. Study lunar geological maps (available from the USGS Astrogeology Center) to understand what you're seeing. The color variations should correlate with known features.

Consider the viewing experience: As the original post notes, the moon looks best in person. A large-aperture telescope (12" or larger) at low power (50-100x) reveals stunning detail and subtle color that cameras struggle to capture. The dynamic range of the human eye combined with the brightness of the moon creates an experience that no screen can replicate.

The Bigger Picture

This Mineral Moon image represents a broader trend in amateur astronomy: the democratization of scientific imaging. What was once the domain of professional observatories is now achievable in backyards. The techniques used here—frame selection, stacking, color processing—are the same principles used in professional astronomical image processing, just scaled down.

The image also highlights an important truth about astrophotography: the raw data is just the beginning. The final image is a product of both capture and processing skill. Understanding the science behind what you're imaging—whether it's lunar mineralogy, planetary atmospheres, or galactic structure—makes the final result more meaningful.

For those interested in exploring further, the Planetary Imaging Resource offers tutorials on lunar processing, and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter provides detailed compositional maps for comparison.

The moon may seem familiar, but through the lens of careful imaging and processing, it reveals itself as a complex, geologically diverse world. Each crater, mare, and highland tells a story of impact, volcanism, and billions of years of solar system history. The Mineral Moon technique is just one way to read that story.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion