MIT's Pappalardo Apprentice Program combines hands-on fabrication training with peer mentoring, celebrating 10 years of teaching metallurgy, machining, and casting through ambitious projects like replica Herreshoff windlasses.

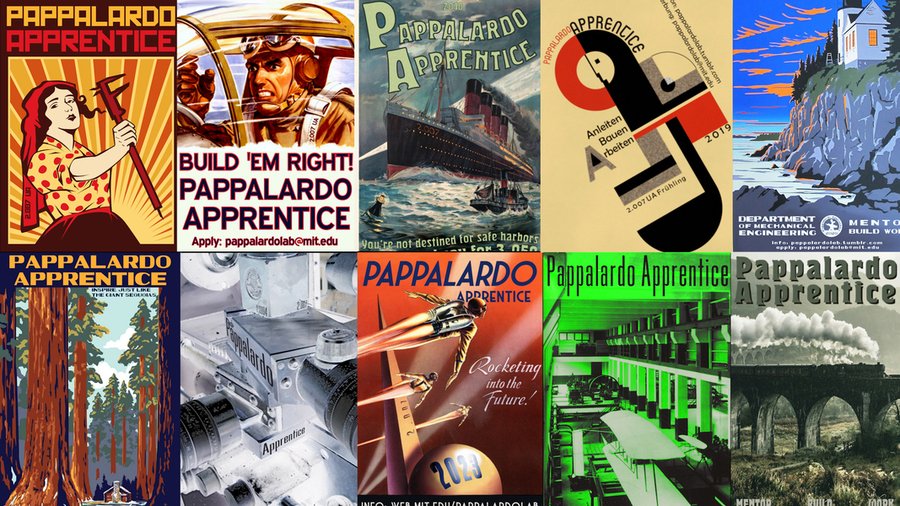

For a decade, MIT's Pappalardo Apprentice Program has been quietly revolutionizing how mechanical engineering students learn fabrication skills while simultaneously teaching their peers. What began as a solution to staffing needs in the popular 2.007 (Design and Manufacturing I) course has evolved into one of the most distinctive educational experiences on campus, blending metallurgy, mentorship, and hands-on learning in ways that traditional classroom settings simply cannot match.

At its core, the program addresses a fundamental challenge in engineering education: how do you teach students to truly understand materials and manufacturing processes when most curricula focus on theory rather than practice? Daniel Braunstein, senior lecturer in mechanical engineering and director of the Pappalardo Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories, recognized that third- and fourth-year students were hungry for deeper fabrication knowledge but lacked opportunities to develop these skills systematically.

"This apprenticeship was largely born of my need for additional lab help during our larger sophomore-level design course, and the desire of third- and fourth-year students to advance their fabrication knowledge and skills," Braunstein explains. The genius of the program lies in its dual purpose: apprentices receive intensive training in advanced manufacturing techniques while simultaneously serving as peer mentors for younger students in 2.007.

The apprenticeship experience is structured around a progression of increasingly complex projects. Junior apprentices begin by fabricating Stirling engines, closed-cycle heat engines that convert thermal energy into mechanical work. These projects provide foundational experience with precision machining, assembly, and the principles of thermodynamics in action. Senior apprentices, however, tackle far more ambitious group projects involving metal casting.

Previous years have seen the creation of an early 20th-century single-cylinder marine engine and a 19th-century torpedo boat steam engine, both now on permanent exhibit at the MIT Museum. This spring, the apprentices are working on something particularly special: a replica of an 1899 anchor windlass from the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company, used on the famous New York 70 class sloops.

These racing yachts, designed by MIT Class of 1870 alumnus Nathanael Greene Herreshoff for wealthy New York Yacht Club members, represented the pinnacle of late 19th-century yacht design. The windlasses they used were robust mechanical devices essential for managing substantial anchors, and recreating them requires apprentices to work from century-old drawings with little documentation of the original manufacturing processes.

"[Looking at these old drawings] we don't know how they made [the parts]," Braunstein notes. "So, there is an element of the discovery of what they may or may not have done. It's like technical archaeology."

This detective work extends beyond mere replication. The apprentices must make critical decisions about material selection, particularly when working with copper alloys for the windlass components. As Braunstein discovered, many students had limited exposure to metallurgy despite its fundamental importance to engineering design.

"The more we got into casting, I was modestly surprised that [the students' exposure to metals] was very limited. So that really launched not just a project, but also a more specific curriculum around metallurgy," he says. This realization led to a deeper integration of materials science into the program, with apprentices learning to make informed decisions about which alloys to use based on mechanical properties, casting characteristics, and historical accuracy.

The hands-on nature of the work extends to every aspect of the windlass project. Apprentices use computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) software to create mold patterns, which are then machined using CNC equipment. The patterns are used to create sand molds for casting the various windlass components. This process requires a deep understanding of pattern-making principles, shrinkage allowances, and the behavior of molten metal.

"You're really just relying on your knowledge of the windlass system, how it's meant to work, which surfaces are really critical, and kind of just applying your intuition," says apprentice Saechow Yap. The work demands both technical precision and creative problem-solving, as apprentices must often improvise solutions to challenges that arise during the casting process.

Beyond the technical skills, the program places significant emphasis on developing teaching and mentoring abilities. Apprentices serve as undergraduate lab assistants for 2.007, helping students with machining operations, hand-tool use, brainstorming sessions, and general peer support. This peer-to-peer learning model creates a unique educational dynamic where knowledge flows in multiple directions.

"I did not just learn how to make things. I got empowered... [to] make anything," says apprentice Wilhem Hector, capturing the transformative nature of the experience. The program's impact extends far beyond the technical skills acquired, fostering confidence, problem-solving abilities, and a deep appreciation for the craft of engineering.

The Pappalardo Lab, established through a gift from Neil Pappalardo '64, proudly calls itself the "most wicked labs on campus"—"wicked," for readers outside of Greater Boston, being local slang that generally means something is pretty awesome. For many apprentices, it becomes their favorite place on campus, a space where theoretical knowledge meets practical application in ways that are both challenging and deeply rewarding.

Braunstein deliberately chose the term "apprenticeship" to emphasize MIT's relationship with the industrial character of engineering. "MIT has a strong heritage in industrial work; that's why we were founded. It was not a science institution; it was about the mechanical arts. And I think the blend of the industrial, plus the academic, is what makes this lab particularly meaningful."

As the program celebrates its 10th anniversary, its success is measured not just in the projects completed or the skills acquired, but in the relationships formed and the community built. "They come in, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, and then to see them go to people who are capable of pouring iron, tramming mills, teaching other people how to do it and having this tight group of friends... that's fun to watch," Braunstein reflects.

The Pappalardo Apprentice Program represents a powerful model for engineering education, one that recognizes that true understanding comes not just from studying how things work, but from making them with your own hands. In an era where many engineering programs have moved away from hands-on fabrication, MIT's commitment to maintaining and expanding these opportunities through programs like this ensures that its graduates understand not just the science of engineering, but its art and craft as well.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion