New research demonstrates that earthquakes reversing direction mid-rupture can occur along straight fault lines under specific friction and propagation conditions, challenging assumptions about seismic complexity.

Seismologists have long documented earthquakes that rupture outward from a hypocenter before unexpectedly reversing course—a phenomenon termed "boomerang" or "back-propagating" seismicity. These events were historically attributed to complex fault geometries, such as intersecting fractures or sharp bends. However, new MIT research published in AGU Advances reveals that even geometrically simple faults—like California's San Andreas segments—can generate boomerang earthquakes under precise physical conditions. This finding suggests such events may be significantly more common than seismic data indicates, with implications for earthquake hazard modeling and structural engineering.

Simulating Seismic Reversals

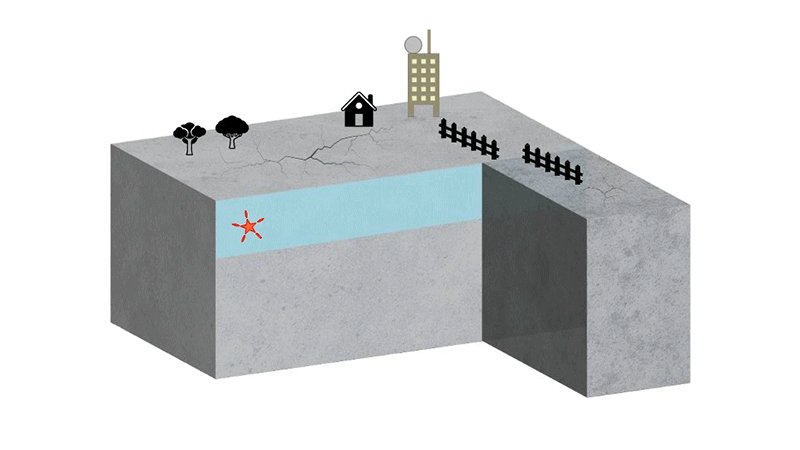

The MIT team, led by graduate student Yudong Sun and geophysics professor Camilla Cattania, employed computational models to isolate the physics of fault rupture. They represented Earth's crust as an elastic medium containing a single straight fault—eliminating geometric complexity as a variable. Using dynamic rupture simulations, they tested how earthquakes propagate under varying parameters: fault length, hypocenter depth, and rupture direction (unilateral or bilateral).

Crucially, the simulations incorporated rate-and-state friction laws, which describe how friction between fault surfaces evolves during sliding. This model captures the rapid stress drops and rebounds that occur as rocks fracture. When simulating unilateral ruptures (those propagating in one direction), the team observed secondary rupture fronts splitting from the main quake and traveling backward along the fault—a boomerang effect.

Friction Dynamics Enable Back-Propagation

The researchers identified three interdependent conditions enabling boomerang behavior:

- Unilateral Propagation: The rupture must travel predominantly in one direction rather than symmetrically outward.

- Rapid Friction Fluctuations: Friction must decrease abruptly to initiate sliding, then temporarily increase (causing sliding to halt), before decreasing again to allow renewed movement. This "stick-slip-restick" sequence creates localized stress build-up behind the main rupture front.

- Sufficient Rupture Distance: The quake must propagate far enough (typically kilometers) for friction cycles to accumulate. "Large earthquakes aren't scaled-up small ones; they exhibit unique rupture behaviors," Sun notes.

Mathematical analysis revealed that during unilateral propagation, sliding deceleration increases friction in narrow fault segments. Once halted, these segments accumulate stress until friction decreases again, triggering backward rupture. This mechanism differs fundamentally from multi-fault interactions previously assumed necessary for back-propagation.

Real-World Implications and Undetected Cases

The study suggests boomerang events may have occurred undetected in historical quakes along simple faults, including the 2023 M7.8 Turkey-Syria earthquake. Because seismic networks often lack the resolution to identify backward-propagating fronts, Cattania explains: "Ground motion is complex, and current methods may miss these reversals." Yet their impact is tangible—rupture direction amplifies ground shaking in its path. Structures already weakened by the initial rupture wave experience intensified damage when the boomerang returns.

This insight necessitates updates to hazard models. Regions with mature, straight faults (like segments of the San Andreas) could experience boomerang quakes if unilateral ruptures meet the friction and distance criteria. Detecting these events requires advanced techniques like distributed acoustic sensing or high-rate GPS, which can resolve rapid directional changes in fault slip.

Future Research Directions

The MIT team emphasizes that validating their model against field observations is critical. Future work will analyze seismic records from historical quakes to identify overlooked back-propagating fronts. Additionally, laboratory experiments simulating friction cycles in rock samples could refine the rate-and-state parameters used in simulations.

"Our work shows that rupture complexity arises from friction physics, not just fault geometry," Cattania concludes. "Understanding this could reshape how we anticipate where—and how severely—earthquakes strike."

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion