NASA's bold claim to beat China back to the moon is undercut by decades of political blunders, underfunded initiatives, and technical delays that have handed Beijing a potential lead. With SpaceX's Starship facing hurdles and Artemis timelines slipping, Blue Origin's unorthodox Mark 1 lander proposal emerges as a credible lifeline to reclaim lunar supremacy before 2030.

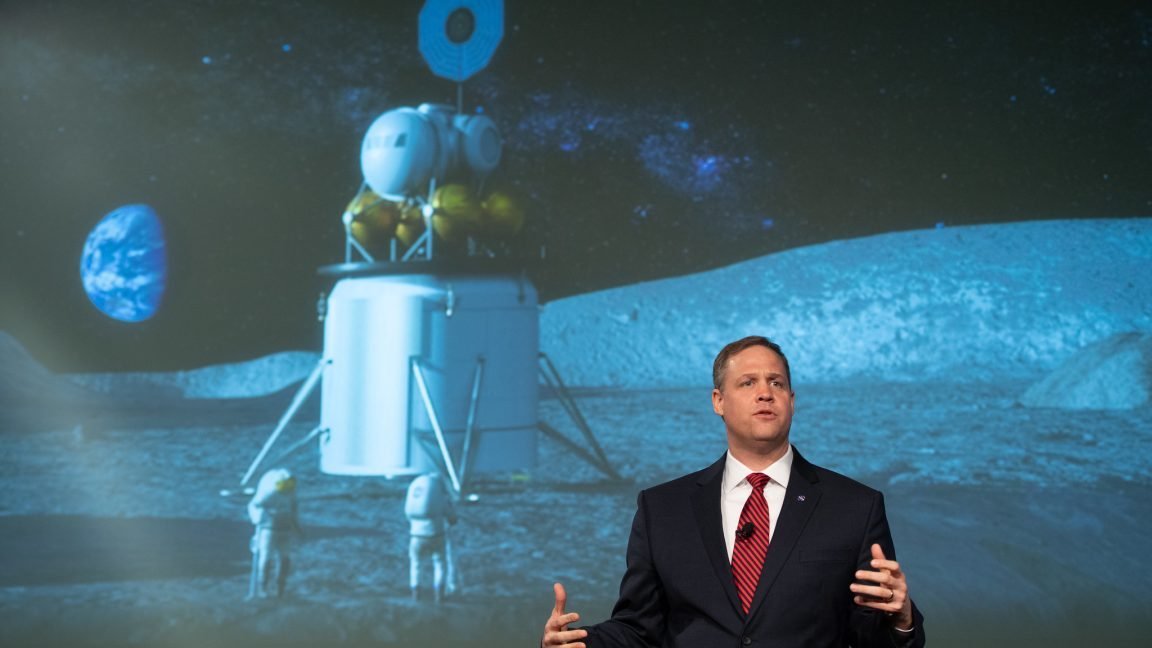

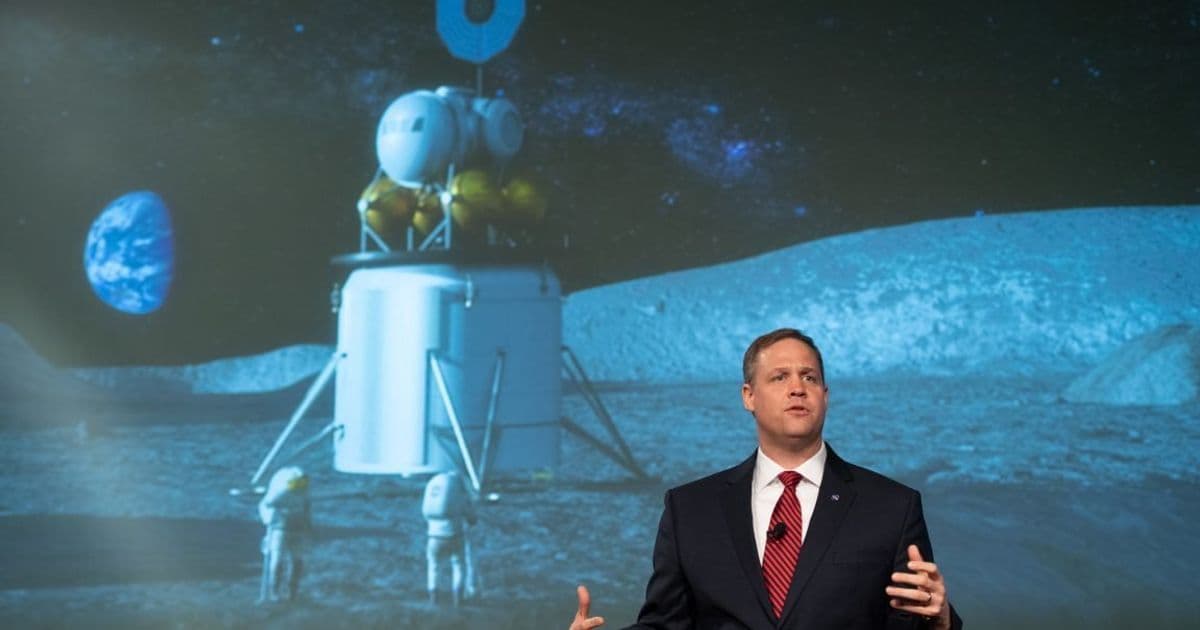

For over a month, NASA Interim Administrator Sean Duffy has trumpeted a singular message across global stages: "We are going to beat the Chinese to the Moon." Yet, this confident assertion clashes starkly with the private acknowledgments of industry insiders and even agency veterans. Former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine voiced the uncomfortable truth in September: "Unless something changes, it is highly unlikely the United States will beat China’s projected timeline to the Moon’s surface." As China targets a crewed lunar landing as early as 2029, America’s path to the moon is mired in a saga of avoidable missteps—and the clock is ticking.

A Legacy of Missed Opportunities The roots of NASA’s current predicament trace back to 2003, a pivotal year marked by tragedy and rising competition. The loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia forced a reckoning on NASA’s future, leading to President George W. Bush’s Constellation Program—a return-to-the-moon initiative dubbed "Apollo on Steroids." Yet Constellation quickly unraveled. Underfunded by Congress and plagued by delays, it prioritized cost-plus contracts for legacy contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, yielding little beyond paper designs. As historian John Logsdon notes, the post-Columbia era was meant to reignite ambition, but it devolved into a fiscal quagmire.

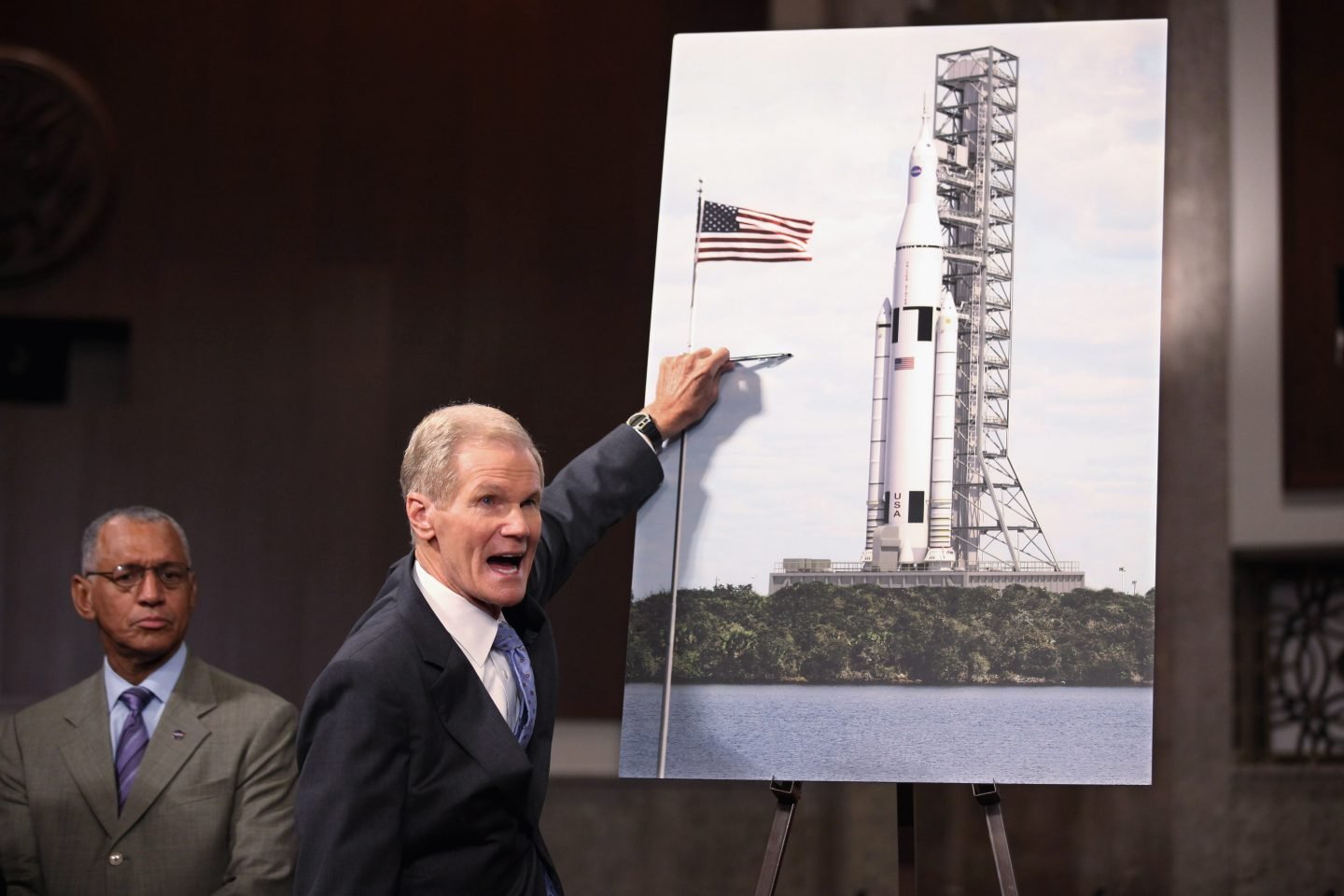

Simultaneously, China’s first crewed spaceflight with Yang Liwei signaled its ascent. While NASA floundered, Beijing methodically expanded its capabilities, progressing from lunar orbiters to a coherent moon-landing strategy. By 2010, the Obama administration attempted a reset, proposing to scrap Constellation’s costly, shuttle-derived rockets in favor of commercial alternatives. Congress rebuffed this, mandating the Space Launch System (SLS)—a rocket architecturally tied to shuttle-era technology to protect contractor interests. This decision, born of political compromise, consumed over $3 billion annually for a decade, diverting funds from critical lunar hardware like landers and suits. "The result was a rocket to nowhere," critics observed, as SLS soaked up resources while offering no clear mission.

The Artemis Gambit and Starship’s Struggle NASA’s pivot to the Artemis Program under the Trump administration refocused efforts on the moon, but structural issues persisted. The agency’s 2021 selection of SpaceX’s Starship as the sole human landing system—awarded just $2.9 billion compared to SLS’s $30 billion—highlighted a desperate bid for affordability. Yet Starship, while revolutionary, is not optimized for lunar timelines. Treated as a "sidequest" to SpaceX’s Mars ambitions, it faces daunting technical hurdles: frequent orbital launches, cryogenic propellant transfer in space, and landing a 160-foot-tall vehicle on uneven lunar terrain. Each lunar mission could require 20-40 Starship tanker flights, a logistical nightmare with no real-world data. Privately, SpaceX targets 2028 for readiness, but as one industry source lamented, "That seems wildly optimistic—especially with China’s steady progress."

Blue Origin’s Unexpected Lifeline With NASA’s options narrowing, an unconventional solution is gaining traction: Blue Origin’s Mark 1 lunar lander. Originally designed for cargo, the Mark 1 has completed assembly and will undergo vacuum testing ahead of a 2026 pathfinder mission. Crucially, Blue Origin has quietly begun adapting it for crewed missions, leveraging lessons from its human-rated Mark 2 lander development. The approach? Use multiple Mark 1 vehicles—no refueling needed—to ferry astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface and back. This avoids Starship’s complexity and could slash years off the timeline. NASA insiders confirm the concept is feasible, and founder Jeff Bezos, eager to counter SpaceX’s dominance, is reportedly "intrigued."

Why This Moment Demands Decisiveness Duffy’s bullish rhetoric now rings hollow against workforce cuts and contractor struggles. Alternatives like shrinking Starship or reviving Apollo-era landers are impractical—one hinges on Musk’s cooperation, the other ignores legacy contractors’ chronic delays. The Mark 1, however, offers a near-term, refueling-free architecture. If NASA acts swiftly to formalize and fund this pivot, it could position the U.S. for a lunar landing by the late 2020s. The stakes extend beyond prestige: losing the moon race cedes strategic high ground in space resource utilization and deep-space exploration. As Bridenstine warned, without radical change, America’s next moonwalk may follow China’s footsteps.

Source: Adapted from Eric Berger's reporting in Ars Technica.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion