A practical breakdown of how SeaTunnel's Change Data Capture works across three stages—Snapshot, Backfill, and Incremental—using real-world analogies to explain its parallel processing and exactly-once guarantees.

When you need to synchronize data from a live database like Oracle, MySQL, or SQL Server without locking tables or causing significant downtime, Change Data Capture (CDC) is the standard approach. But the mechanics behind it can be opaque. SeaTunnel, an Apache project, implements CDC with a specific three-stage process designed to balance speed and data consistency. Understanding this process reveals how modern data pipelines handle the challenge of reading a database that's constantly changing.

The core challenge is simple: you can't read a database in a single instant. A snapshot takes time, and during that time, writes continue. If you only read the snapshot, you end up with a mix of old and new data. SeaTunnel's solution is a trilogy of stages: Snapshot, Backfill, and Incremental, each with a distinct role.

The Three Stages of CDC

The overall CDC data reading process is broken down into three major stages: Snapshot (Full Load), Backfill, and Incremental.

1. Snapshot Stage

The Snapshot stage is straightforward: take a snapshot of the current database table data and perform a full table scan via JDBC. For MySQL, this involves recording the current binlog position at the start: SHOW MASTER STATUS;, which gives you the File and Position. SeaTunnel records these as the "low watermark"—the starting point in the log stream.

But SeaTunnel doesn't just read the whole table sequentially. To accelerate the process, it implements its own split cutting logic. Assuming a global parallelism of 10, SeaTunnel analyzes tables and their primary key or unique key ranges to select an appropriate splitting column. It then splits based on the column's maximum and minimum values, with a default snapshot.split.size of 8096 rows.

Large tables can be cut into hundreds of Splits, which are allocated to parallel channels. The enumerator distributes these splits based on subtask requests, aiming for a balanced load. For example, with three tables and a parallelism of 3:

- Table 1 might generate

[Table1-Split0, Table1-Split1, Table1-Split2] - Table 2 might generate

[Table2-Split0, Table2-Split1] - Table 3 might generate

[Table3-Split0, Table3-Split1, Table3-Split2, Table3-Split3]

These splits are then allocated across subtasks:

- Subtask 0:

[Table1-Split0, Table2-Split1, Table3-Split2] - Subtask 1:

[Table1-Split1, Table3-Split0, Table3-Split3] - Subtask 2:

[Table1-Split2, Table2-Split0, Table3-Split1]

Each Split is a query with a range condition, like SELECT * FROM user_orders WHERE order_id >= 1 AND order_id < 10001;. Crucially, each Split records its own low and high watermark.

Practical Advice: Don't make split_size too small. Having too many Splits increases scheduling and memory overhead, which can actually slow things down.

2. Backfill Stage

Why is Backfill needed? Imagine performing a full snapshot of a table that's being frequently written to. When you read the 100th row, the data in the 1st row may have already been modified. If you only read the snapshot, the data you hold when you finish reading is actually "inconsistent"—part old, part new.

The role of Backfill is to compensate for the "data changes that occurred during the snapshot" so that the data is eventually consistent. The behavior of this stage depends heavily on the exactly_once parameter.

2.1 Simple Mode (exactly_once = false)

This is the default mode. The logic is simple and doesn't require memory caching:

- Direct Snapshot Emission: Reads snapshot data and sends it directly downstream without entering a cache.

- Direct Log Emission: Reads Binlog at the same time and sends it directly downstream.

- Eventual Consistency: There will be duplicates in the middle (old A sent first, then new B), but as long as the downstream supports idempotent writes (like MySQL's

REPLACE INTO), the final result is consistent.

2.2 Exactly-Once Mode (exactly_once = true)

This is SeaTunnel CDC's standout feature, guaranteeing data is "never lost, never repeated." It introduces a memory buffer (Buffer) for deduplication.

Simple Explanation: Imagine a teacher asking you to count how many people are in a class right now (Snapshot stage). However, the students are mischievous; while you're counting, people are running in and out (data changes). If you just count with your head down, the result will be inaccurate when you finish.

SeaTunnel's approach:

- Take a Photo First (Snapshot): Count the number of people in the class and record it in a small notebook (memory buffer); don't tell the principal (downstream) yet.

- Watch the Surveillance (Backfill): Retrieve the surveillance video (Binlog log) for the period you were counting.

- Correct the Records (Merge): If the surveillance shows someone just came in, but you didn't count them → add them. If someone just ran out, but you counted them → cross them out. If someone changed their clothes → change the record to the new clothes.

- Submit Homework (Send): After correction, the small notebook in your hand is a perfectly accurate list; now hand it to the principal.

Summary for Beginners: exactly_once = true means "hold it in and don't send it until it's clearly verified."

- Benefit: The data received downstream is absolutely clean, without duplicates or disorder.

- Cost: It needs memory to store data. If the table is particularly large, memory might be insufficient.

2.3 Two Key Questions and Answers

Q1: Why is case READ: throw Exception written in the code? Why aren't there READ events during the Backfill stage?

The READ event is defined by SeaTunnel itself, specifically to represent "stock data read from the snapshot." The Backfill stage reads the database's Binlog. Binlog only records "additions, deletions, and modifications" (INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE) and never records "someone queried a piece of data." Therefore, if you read a READ event during the Backfill stage, it means the code logic is confused.

Q2: If it's placed in memory, can the memory hold it? Will it OOM?

It's not putting the whole table into memory: SeaTunnel processes by splits. Splits are small (a default split has only 8096 rows of data). It throws away after use: After processing a split, send it, clear the memory, and process the next one. Memory occupancy formula ≈ Parallelism × Split size × Single row data size.

2.4 Key Detail: Watermark Alignment Between Multiple Splits

This is a hidden but critical issue. If not handled well, it leads to data loss or repetition.

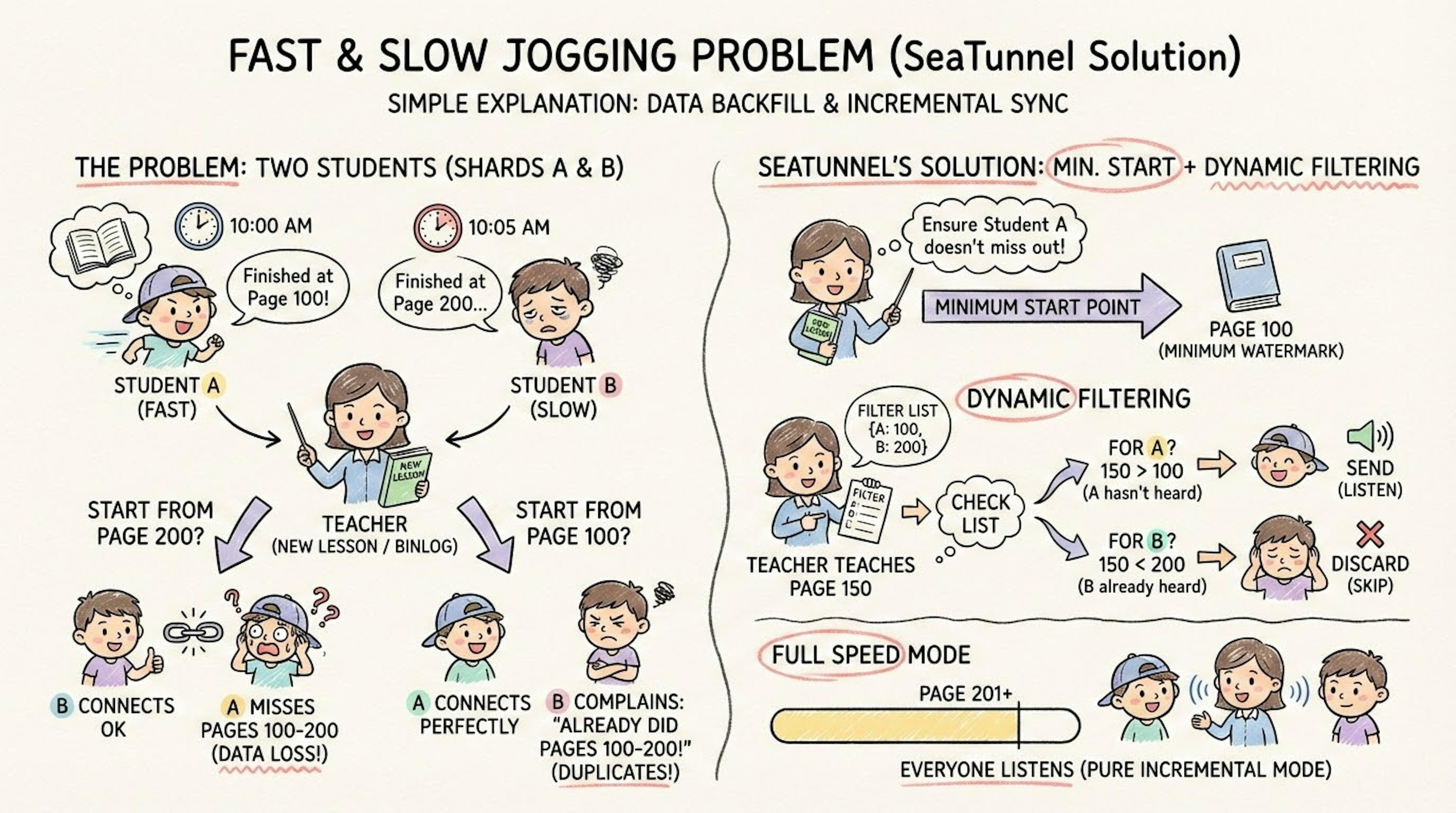

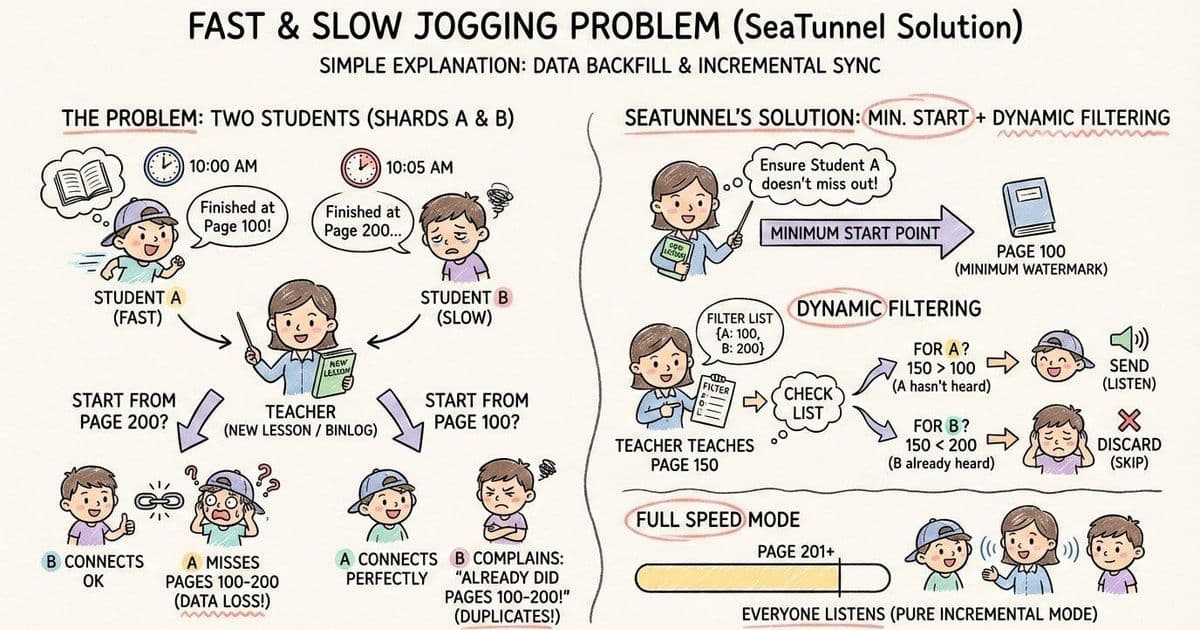

Plain Language Explanation: The Fast/Slow Runner Problem. Imagine two students (Split A and Split B) are copying homework (Backfill data).

- Student A (fast): Copied to page 100 and finished at 10:00.

- Student B (slow): Copied to page 200 and just finished at 10:05.

Now, the teacher (Incremental task) needs to continue teaching a new lesson (reading Binlog) from where they finished copying. Where should the teacher start?

- If starting from page 200: Student B is connected, but the content Student A missed between pages 100 and 200 (what happened between 10:00 and 10:05) is completely lost.

- If starting from page 100: Student A is connected, but Student B will complain: "Teacher, I already copied the content from page 100 to 200!" This leads to repetition.

SeaTunnel's Solution: Start from the earliest and cover your ears for what you've already heard. SeaTunnel adopts a "Minimum Watermark Starting Point + Dynamic Filtering" strategy:

- Determine the Start (care for the slow one): The teacher decides to start from page 100 (the minimum watermark among all splits).

- Dynamic Filtering (don't listen to what's been heard): While the teacher is lecturing (reading Binlog), they hold a list:

{ A: 100, B: 200 }. When the teacher reaches page 150:- Look at the list; is it for A? 150 > 100, A hasn't heard it, record it (send).

- Look at the list; is it for B? 150 < 200, B already copied it, skip it directly (discard).

- Full Speed Mode (everyone has finished hearing): When the teacher reaches page 201 and finds everyone has already heard it, they no longer need the list.

Summary in one sentence: With exactly_once: The incremental stage strictly filters according to the combination of "starting offset + split range + high watermark." Without exactly_once: The incremental stage becomes a simple "sequential consumption from a certain starting offset."

3. Incremental Stage

After the Backfill (for exactly_once = true) or Snapshot stage ends, it enters the pure incremental stage:

- MySQL: Based on binlog.

- Oracle: Based on redo/logminer.

- SQL Server: Based on transaction log/LSN.

- PostgreSQL: Based on WAL.

SeaTunnel's behavior in the incremental stage is very close to native Debezium: it consumes logs in offset order and constructs events like INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE for each change. When exactly_once = true, the offset and split status are included in the checkpoint to achieve "exactly-once" semantics after failure recovery.

Summary

The core design philosophy of SeaTunnel CDC is to find the perfect balance between "Fast" (parallel snapshots) and "Stable" (data consistency). Let's review the key points of the entire process:

- Slicing (Split) is the foundation of parallel acceleration: Cutting large tables into small pieces to let multiple threads work at the same time.

- Snapshot is responsible for moving stock: Utilizing slices to read historical data in parallel.

- Backfill is responsible for sewing the gaps: This is the most critical step. It compensates for changes during the snapshot and eliminates duplicates using memory merging algorithms to achieve Exactly-Once.

- Incremental is responsible for real-time synchronization: Seamlessly connecting to the Backfill stage and continuously consuming database logs.

Understanding this trilogy of "Snapshot → Backfill → Incremental" and the coordinating role of "Watermarks" within it is to truly master the essence of SeaTunnel CDC.

Featured image - SeaTunnel CDC Explained: A Layman’s Guide

Proof of Usefulness: Hackathon is a global 6-month developer challenge designed to reward real-world utility projects and initiatives. With 150,000+ in cash prizes and software credits for winners and $1500+ worth of software and inventory for participants, this is undisputedly the biggest contest of the year. Learn more here.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion