Serverless computing abstracts away server management, letting developers focus on event-driven code. This article examines the operational model, compares it to traditional architectures, and explores the trade-offs between convenience and control that every systems engineer must navigate.

When developers first encounter the term "serverless," the contradiction is immediate. Software runs on computers, so how can there be no servers? The name is a misdirection. Serverless doesn't mean servers have vanished; it means the responsibility for managing them has shifted. You no longer provision machines, patch operating systems, or configure load balancers. Instead, you write functions that run in response to events, and the cloud provider handles the underlying infrastructure.

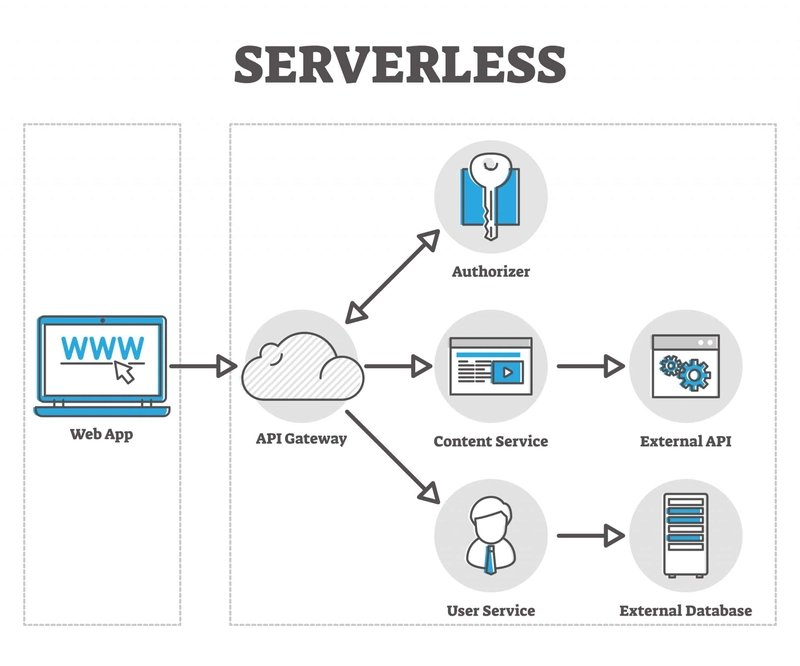

This shift represents a fundamental change in how we think about application architecture. Instead of maintaining a persistent server waiting for requests, you design small, stateless units of code that execute only when triggered. An event could be an HTTP request, a file upload to cloud storage, a message in a queue, or a scheduled cron job. The platform allocates resources, runs your code, and tears everything down when the work is done.

The Operational Model: From Provisioning to Events

In a traditional architecture, you provision servers in advance. You estimate traffic, choose instance types, and set up auto-scaling groups. Those servers run continuously, even during idle periods, and you're responsible for their lifecycle: OS updates, security patches, runtime installations, and health monitoring.

Serverless inverts this model. You define functions and their triggers. The platform manages capacity. If one request arrives, one instance runs. If ten thousand requests hit simultaneously, the platform scales horizontally by running many instances in parallel. When demand drops, instances disappear. You pay only for execution time, not for idle servers.

This event-driven pattern encourages a different architectural style. Applications become collections of functions connected by managed services—databases, message queues, object storage. The state is externalized. Functions themselves are ephemeral, which simplifies deployment but introduces new challenges around consistency and debugging.

Trade-offs: Convenience vs. Control

Advantages

Reduced Operational Overhead: For small teams or individual developers, this is transformative. You can deploy a production-grade API or data pipeline without becoming an expert in infrastructure. The cognitive load shifts from managing machines to writing business logic.

Automatic Scaling: The platform handles elasticity. You don't need to design scaling policies or predict traffic patterns. This is ideal for workloads with unpredictable spikes—like a viral social media feature or a batch processing job that runs on a schedule.

Cost Efficiency for Variable Workloads: For applications with low or sporadic usage, serverless can be significantly cheaper than always-on servers. You avoid paying for idle capacity. However, for high-throughput, predictable workloads, the per-execution pricing model can become expensive compared to reserved instances.

Disadvantages

Cold Start Latency: When a function hasn't been invoked recently, the platform may need to initialize an execution environment—loading the runtime, dependencies, and your code. This adds latency, often ranging from tens to hundreds of milliseconds. For latency-sensitive applications like real-time gaming or high-frequency trading, this can be a deal-breaker. Some platforms offer "provisioned concurrency" to keep instances warm, but that adds cost and complexity.

Architectural Complexity: A serverless application often becomes a distributed system of many small functions. While this enables fine-grained scaling, it also increases complexity. Debugging requires tracing requests across multiple services. You need robust logging, monitoring, and distributed tracing tools to understand failures. The failure modes are different—network partitions, event ordering issues, and eventual consistency become first-class concerns.

Vendor Lock-in and Platform Limits: Serverless platforms impose constraints: execution time limits (often 15 minutes), memory caps, and supported runtimes. You're also tightly coupled to the provider's ecosystem—proprietary event sources, managed services, and deployment tools. Migrating to another cloud or back to self-hosted infrastructure can be difficult.

State Management Challenges: Since functions are stateless, any required state must be stored externally. This introduces latency and complexity. You need to choose appropriate data stores (databases, caches, object storage) and design for consistency. For some workloads, maintaining state in a long-running process is simpler.

When Serverless Makes Sense

Serverless is not a universal solution. It excels in specific scenarios:

- Event-Driven Workflows: Processing files, handling webhooks, or reacting to database changes.

- Scheduled Tasks: Cron jobs, periodic data aggregation, or report generation.

- APIs with Variable Traffic: Prototypes, internal tools, or public APIs with unpredictable usage.

- Data Processing Pipelines: ETL jobs that run on demand or on a schedule.

It's less suitable for:

- Latency-Critical Applications: Where cold starts are unacceptable.

- Long-Running Processes: Exceeding platform time limits.

- High-Throughput, Predictable Workloads: Where reserved instances are more cost-effective.

- Applications Requiring Deep Customization: Where you need fine-grained control over the runtime environment.

The Bigger Picture: Abstraction Layers in Computing

Serverless is part of a broader trend toward abstraction in cloud computing. We've moved from physical servers (IaaS) to virtual machines (IaaS/PaaS) to containers (CaaS) to functions (FaaS). Each layer abstracts away more operational complexity but also reduces control and increases vendor dependence.

For new software engineers, serverless offers a low-friction path to building real systems. It encourages thinking in terms of events, stateless functions, and managed services—patterns that are valuable even when working with traditional architectures.

However, understanding what's happening underneath is crucial. Knowing that real servers execute your code helps you reason about performance, cost, and reliability. When a function times out or a cold start causes a spike in latency, you need to understand the underlying platform to diagnose the issue.

Conclusion

Serverless is neither magic nor a replacement for traditional servers. It's an abstraction layer that shifts responsibility from the developer to the cloud provider. This trade-off—convenience for control—has profound implications for how we design, deploy, and operate software.

The key is to choose the right tool for the job. Serverless can dramatically reduce operational complexity for the right workloads, but it introduces new challenges around distributed systems, debugging, and vendor lock-in. As you build systems, consider the trade-offs: what are you willing to give up for simplicity, and what are the costs of that decision?

Ultimately, serverless is a powerful option in the modern software engineer's toolkit. Understanding its strengths, limitations, and underlying mechanics will help you make informed architectural decisions, whether you're building a student project or a large-scale production system.

For those interested in exploring serverless platforms, here are some resources:

- AWS Lambda Documentation

- Google Cloud Functions

- Azure Functions

- Serverless Framework - an open-source framework for deploying serverless applications

- The Twelve-Factor App - principles that align well with serverless architecture

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion