A software developer reflects on 25 years in the industry, sharing personal stories about learning HTML, debugging, career transitions, and the evolution of their professional identity.

Stories From 25 Years of Computing By Susam Pal on 06 Feb 2026 Last year, I completed 20 years in professional software development. I wanted to write a post to mark the occasion back then, but couldn't find the time. This post is my attempt to make up for that omission. In fact, I have been involved in software development for slightly longer than 20 years. Although I had my first taste of computer programming as a child, it was only when I entered university about 25 years ago that I seriously got into software development. So I'll start my stories from there.

These stories are less about software and more about people. Unlike many career anniversary posts, this one contains no grand wisdom or lessons. Just a collection of stories. I hope you'll enjoy at least a few of them.

Contents My First Lesson in HTML The Reset Vector My First Job Sphagetti Code Animated Television Widgets Good Blessings The CTF Scoreboard

My First Lesson in HTML The first story takes place in 2001, shortly after I joined university. One evening, I went to the university computer laboratory to browse the web. Out of curiosity, I typed susam.com into the address bar to see what kind of website existed there. I ended up on this home page: susam.com. It looked much larger back then because display resolutions were lower, so the text and banner covered almost half the screen.

I was simply trying to make sense of the Internet. I remember wondering what it would take to create my own website, perhaps at susam.com. That's when an older student who had been watching me browse over my shoulder approached and asked whether that was my name and if I had created the website. I told him I hadn't and that I had no idea how websites were made.

He asked me to move aside, took my seat and clicked View > Source in Internet Explorer. He then explained how websites are made of HTML pages and how those pages are simply text instructions. Next, he opened Notepad and wrote a simple HTML page containing nothing but a tag with 'HELLO' inside it, then showed me how it appeared in the browser. He demonstrated a few more things as well, such as using the tag to change colour, typeface and size.

It was only a brief ten-minute tutorial, but it made the World Wide Web feel much less mysterious and far more fascinating. That person had an ulterior motive though. After the tutorial, he never gave the seat back to me. He just continued browsing the Web and waited for me to leave. I was too timid to ask for my seat back. Seats were limited, so I returned to my dorm room both disappointed that I couldn't continue browsing that day and excited about all the websites I might create with this newfound knowledge.

I could never register susam.com for myself though. That domain was always used by some business selling Turkish cuisines. Eventually, I managed to get the next best thing: a .net domain of my own. That brief encounter in the university laboratory set me on a lifelong path of creating and maintaining personal websites.

The Reset Vector The second story also comes from my university days. I was hanging out with my mates in the computer laboratory. In front of me was MS-DOS running on a machine with an Intel 8086 processor. I think I was working on a lift control program when my mind drifted to a small detail about the 8086 microprocessor that we had recently learnt in a lecture.

Our professor had explained that when the 8086 is reset, execution begins with CS:IP set to FFFF:0000. So I murmured to anyone who cared to listen, 'I wonder if the system will reboot if I jump to FFFF:0000.' I then opened DEBUG.EXE and jumped to that address.

C:>DEBUG G =FFFF:0000

The machine rebooted instantly. One of my friends, who topped the class every semester, had been watching over my shoulder. As soon as the machine restarted, he exclaimed, 'How did you do that?'

I explained that the reset vector is located at physical address FFFF0, and that the CS:IP value FFFF:0000 maps to that address in real mode. After that, I went back to working on my lift control program and didn't think much more about the incident.

About a week later, the same friend came to my dorm room. He sat down with a very serious expression and asked, 'How did you know to do that? How did it occur to you to jump to the reset vector?'

I must have said something like, 'It just occurred to me. I remembered that detail from the lecture and wanted to try it out.' He then said, 'I want to be able to think like that. I come top of the class every year, but I don't think the way you do. I would never have thought of taking a small detail like that and testing it myself.'

He responded, 'And that's exactly it. It would never occur to me to try something like that. I feel disappointed that I keep coming top of the class, yet I am not curious in the same way you are. I've decided I don't want to top the class anymore. I just want to explore and experiment with what we learn, the way you do.'

That was all he said before getting up and heading back to his dorm room. I didn't take it very seriously at the time. I couldn't imagine why someone would willingly give up the accomplishment of coming first every year. But I was wrong. He never topped the class again. He still ranked highly, often within the top ten, but he kept his promise of never finishing first again.

To this day, I remember the incident fondly. I still feel a mix of embarrassment and pride at having inspired someone to step back academically in order to have more fun with learning. Of course, there is no reason one cannot do both. But in the end, that was his decision, not mine.

My First Job In my first job, I was assigned to work on the installer for a specific component of an e-banking product. The installer was written in Python and was quite fragile. During my first week on the project, I spent much of my time stabilising the installer and writing a user guide with step-by-step instructions on how to use it. The result was well received and appreciated by both my seniors and management.

To my surprise, my user guide was praised more than my improvements to the installer. While the first few weeks were enjoyable, I soon realised I would not find the work fulfilling for very long. I wrote to management a few times to ask whether I could transfer to a team where I could work on something more substantial. My emails were initially met with resistance. After several rounds of discussion, however, someone who had heard about my situation reached out and suggested a team whose manager might be interested in interviewing me.

The team was based in a different city. I was young and willing to relocate wherever I could find good work, so I immediately agreed to the interview. This was in 2006, when video conferencing was not yet common. On the day of the interview, the hiring manager called me on my desk phone. He began by introducing the team, which called itself Archie, short for architecture. The team developed and maintained the web framework and core architectural components on which the entire e-banking product was built.

The product had existed long before open source frameworks such as Spring or Django became popular, so features such as API routing, authentication and authorisation layers, cookie management and similar capabilities were all implemented in-house by this specialised team. Because the software was used in banking environments, it also had to pass strict security testing and audits to minimise the risk of serious flaws.

The interview began well. He asked several questions related to software security, such as what SQL injection is and how it can be prevented or how one might design a web framework that mitigates cross-site scripting attacks. He also asked programming questions, most of which I answered pretty well. Towards the end, however, he asked how we could prevent MITM attacks. I had never heard the term, so I admitted that I did not know what MITM meant.

He then asked, 'Man in the middle?' but I still had no idea what that meant or whether it was even a software engineering concept. He replied, 'Learn everything you can about PKI and MITM. We need to build a digital signatures feature for one of our corporate banking products. That's the first thing we'll work on.'

Over the next few weeks, I studied RFCs and documentation related to public key infrastructure, public key cryptography standards and related topics. At first, the material felt intimidating, but after spending time each evening reading whatever relevant literature I could find, things gradually began to make sense. Concepts that initially seemed complex and overwhelming eventually felt intuitive and elegant.

I relocated to the new city a few weeks later and delivered the digital signatures feature about a month after joining the team. We used the open source Bouncy Castle library to implement digital signatures, which became my first real interaction with the open source community. After that I worked on other parts of the product too. The most rewarding part was knowing that the code I was writing became part of a mature product used by hundreds of banks and millions of users.

It was especially satisfying to see the work pass security testing and audits and be considered ready for release. That was my first real engineering job. My manager also turned out to be an excellent mentor. Working with him helped me develop new skills and his encouragement gave me confidence that stayed with me for years. Nearly two decades have passed since then, yet the product apparently still exists. In fact, in my current phase of life I sometimes happen to use that product as a customer. Sometimes, I open the browser developer tools to view the page source and can still see traces of the HTML generated by code I wrote almost twenty years ago.

Sphagetti Code Around 2007 or 2008, I began working on a proof of concept for developing widgets for an OpenTV set-top box. The work involved writing code in a heavily trimmed-down version of C. One afternoon, while making good progress on a few widgets, I noticed that they would occasionally crash at random. I tried tracking down the bugs, but I was finding it surprisingly difficult to understand my own code. I had managed to produce some truly spaghetti-like code, complete with dubious pointer operations that were almost certainly responsible for the crashes, yet I could not pinpoint where exactly things were going wrong.

Ours was a small team of four people, each working on an independent proof of concept. The most senior person on the team acted as our lead and architect. Later that afternoon, I showed him my progress and explained that I was still trying to hunt down the bugs causing the widgets to crash. He asked whether he could look at the code. After going through it briefly and probably realising that it was a bit of a mess, he asked me to send him the code as a tarball, which I promptly did. He then went back to his desk to study the code.

I remember thinking, 'There is no way he is going to find the problem. I have been debugging this for hours and even I barely understand what I have written. This is the worst spaghetti code I have ever produced.' With little hope of a quick solution, I went back to debugging on my own. Barely five minutes later, he came back to my desk and asked me to open a specific file. He then showed me exactly where the pointer bug was. It had taken him only a few minutes not only to read my tangled code but also to understand it well enough to identify the fault and point it out.

As soon as I fixed that line, the crashes disappeared. I was genuinely in awe of his skill. I have always loved computing and programming, so I had assumed I was already fairly good at it. That incident, however, made me realise how much further I still had to go before I could consider myself a good software developer. I did improve significantly in the years that followed and today I am far better at managing software complexity than I was back then.

Animated Television Widgets In another project from that period, we worked on another set-top box platform that supported Java Micro Edition (Java ME) for widget development. One day, the same architect from the previous story asked whether I could add animations to the widgets. I told him that it should be possible. To make this story clearer, though, I need to explain how the different stakeholders in the project were organised.

Our small team effectively played the role of the software vendor. The final product going to market would carry the brand of a major telecom carrier, offering direct-to-home (DTH) television services, with the set-top box being one of the products sold to customers. The set top box was manufactured by another company. So the project was a partnership between three parties: our company as the software vendor, the telecom carrier and the set-top box manufacturer.

The telecom carrier wanted to know whether widgets could be animated on screen with smooth slide-in and slide-out effects. That was why the architect approached me to ask whether it could be done, and I told him it should be possible. I then began working on animating the widgets. Meanwhile, the architect and a few senior colleagues attended a business meeting with all the partners present. During the meeting, he explained that we were evaluating whether widget animations could be supported.

The set-top box manufacturer immediately dismissed the idea, saying, 'That's impossible. Our set-top box does not support animation.' When the architect returned and shared this with us, I replied, 'I do not understand. If I can draw a widget, I can animate it too. All it takes is clearing the widget and redrawing it at slightly different positions repeatedly. In fact, I already have a working version.' I then showed a demo of the animated widgets running on the emulator.

The following week, the architect attended another partners' meeting where he shared updates about our animated widgets. I was not personally present, so what follows is second-hand information passed on by those who were there. I learnt that the set-top box company reacted angrily. For some reason, they were unhappy that we had managed to achieve results using their set-top box and APIs that they had officially described as impossible. They demanded that we stop work on animation immediately, arguing that our work could not be allowed to contradict their official position. If I remember correctly, there were even suggestions of legal consequences.

At that point, the telecom carrier's representative intervened and bluntly told the set top box representative to just shut up. If the set top box guy was furious, the telecom guy was even more so, 'You guys told us animation was not possible and these people are showing that it is. You manufacture the set-top box. How can you not know what it is capable of?'

Meanwhile, I continued working and completed my proof-of-concept implementation. It worked very well in the emulator, but I did not yet have access to the actual hardware. The device was still in the process of being shipped to us, so all my early proof-of-concepts ran on the emulator.

The following week, the architect planned to travel to the set-top box company's office to test my widgets on the real hardware. At the time, I was quite proud of having apparently proven the manufacturer wrong. Here I was, an engineer in his twenties working on one of my first major projects, already demonstrating capabilities that even the hardware maker believed were impossible.

But when the architect travelled to test the widgets on the actual device, a problem emerged. What looked like buttery smooth animation on the emulator appeared noticeably choppy on a real television. Over the next few weeks, I experimented with frame rates, buffering strategies and optimising the computation done in the the rendering loop. Each week, the architect travelled for testing and returned with the same report: the animation was still choppy.

The modest embedded hardware could not keep up with the required computation and rendering. In the end, the telecom carrier decided that no animation was better than poor animation and dropped the idea altogether. So in the end, the set-top box developers turned out to be correct after all.

Good Blessings Back in 2009, after completing about a year at RSA Security, I began looking for work that felt more intellectually stimulating, especially projects involving mathematics and algorithms. I spoke with a few senior leaders about this, but nothing materialised for some time. Then one day, Dr Burt Kaliski, Chief Scientist at RSA Laboratories, asked to meet me to discuss my career aspirations.

I have written about this in more detail in another post here: Good Blessings. I will summarise what followed. Dr Kaliski met me and offered a few suggestions about the kinds of teams I might approach to find more interesting work. I followed his advice and eventually joined a team that turned out to be an excellent fit. I remained with that team for the next six years.

During that time, I worked on parser generators, formal language specification and implementation, as well as indexing and querying components of a petabyte-scale database. I learnt something new almost every day during those six years, and it remains one of the most enjoyable periods of my career. I have especially fond memories of working on parser generators alongside remarkably skilled engineers from whom I learnt a lot.

Years later, I reflected on how that brief meeting with Dr Kaliski had altered the trajectory of my career. I realised I was not sure whether I had properly expressed my gratitude to him for the role he had played in shaping my path. So I wrote to thank him and explain how much that single conversation had influenced my life. A few days later, Dr Kaliski replied, saying he was glad to know that the steps I took afterwards had worked out well. Before ending his message, he wrote this heart-warming note: 'One of my goals is to be able to provide encouragement to others who are developing their careers, just as others have invested in mine, passing good blessings from one generation to another.'

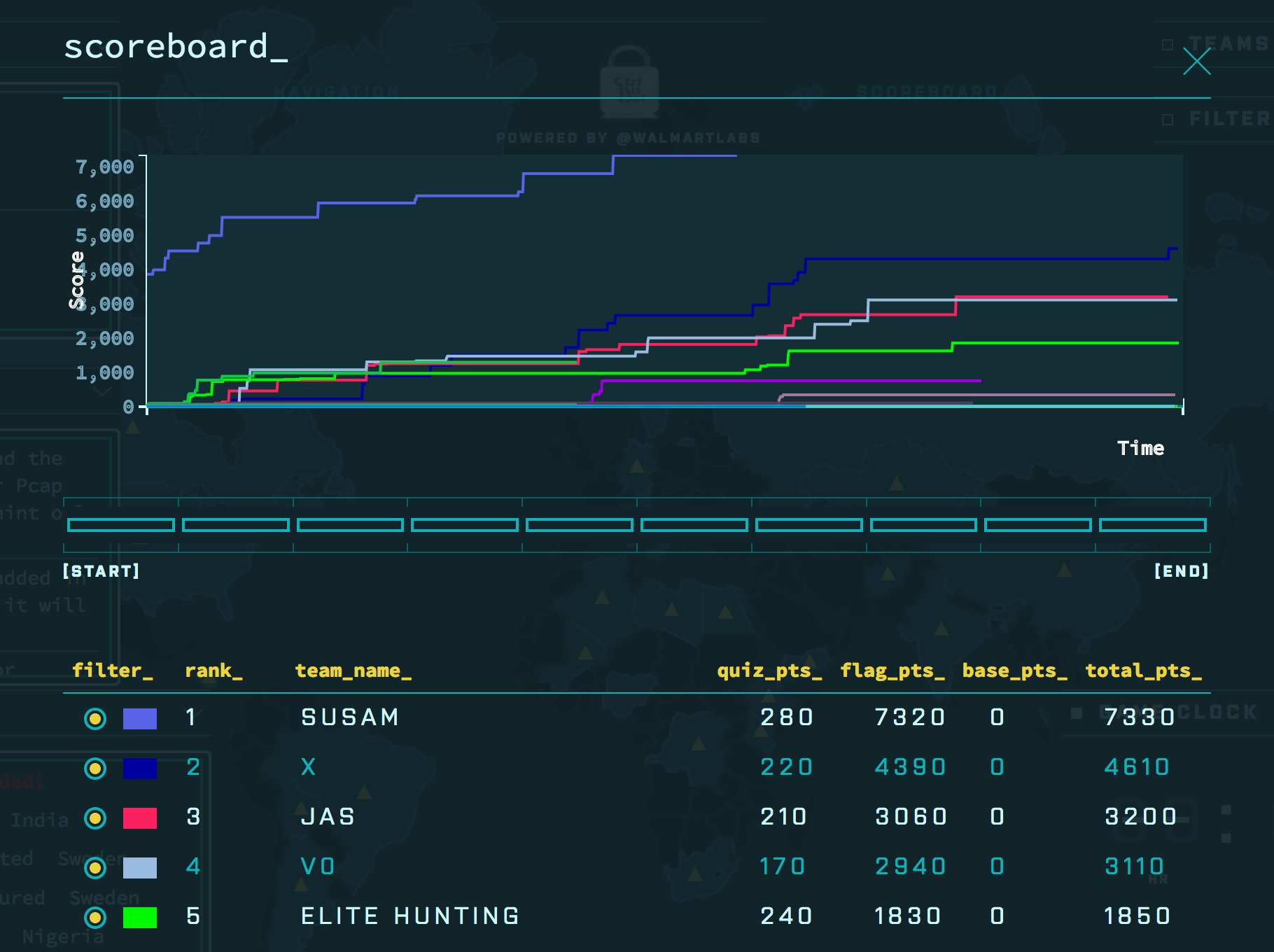

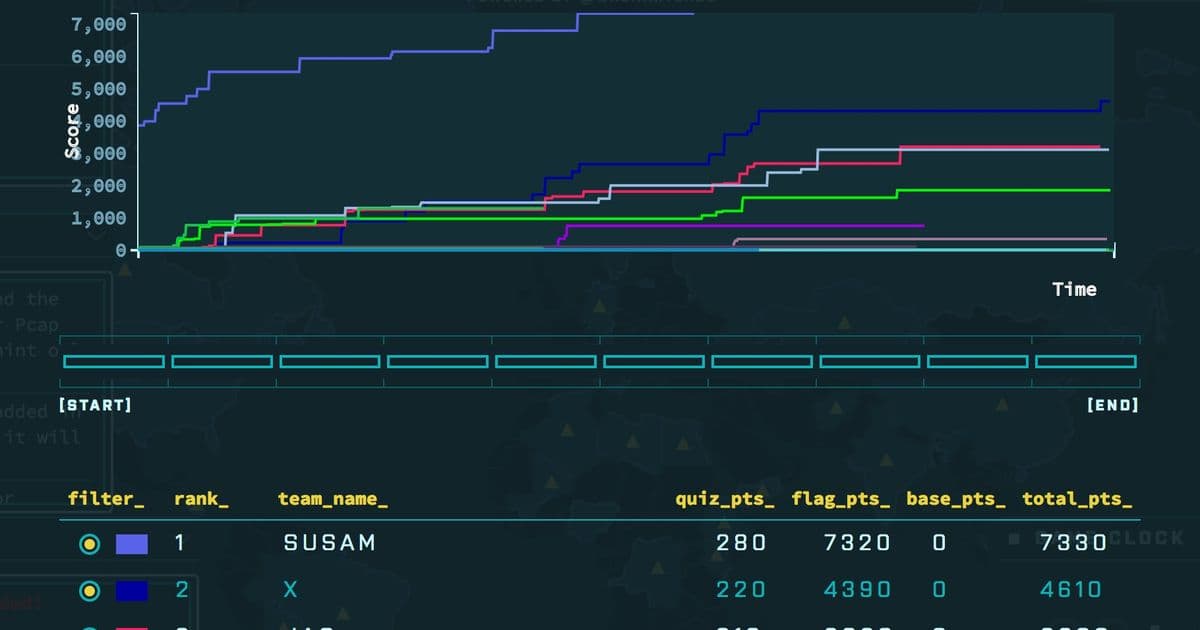

The CTF Scoreboard This story comes from 2019. By then, I was no longer a twenty-something engineer just starting out. I was now a middle-aged staff engineer with years of experience building both low-level networking systems and database systems. Most of my work up to that point had been in C and C++. I was now entering a new phase where I would be developing microservices professionally in languages such as Go and Python.

None of this was unfamiliar territory. Like many people in this profession, computing has long been one of my favourite hobbies. So although my professional work for the previous decade had focused on C and C++, I had plenty of hobby projects in other languages, including Python and Go. I cannot even say that I missed working in C and C++. After all, who wants to spend their days chasing memory bugs in core dumps when you could be building features and delivering real value to customers?

In October 2019, during Cybersecurity Awareness Month, a Capture the Flag (CTF) event was organised at our office. The contest featured all kinds of puzzles, ranging from SQL injection challenges to insecure cryptography problems. Some challenges also involved reversing binaries and exploiting stack overflow vulnerabilities. I am usually rather intimidated by such contests. The whole idea of competitive problem-solving under time pressure tends to make me nervous. But one of my colleagues persuaded me to participate in the CTF. And, somewhat to my surprise, I turned out to be rather good at it.

Within about eight hours, I had solved roughly 90% of the puzzles. I finished at the top of the scoreboard.

In my younger days, I was generally known to be a good problem solver. I was often consulted when thorny problems needed solving and I usually managed to deliver results. I also enjoyed solving puzzles. I had a knack for them and happily spent hours, sometimes days, working through obscure mathematical or technical puzzles and sharing detailed write-ups with friends of the nerd variety. So tackling arcane and seemingly pointless puzzles was very much my thing. Seen in that light, my performance at the CTF probably should not have surprised me. Still, I was very pleased. It was reassuring to know that I could still rely on my systems programming experience to solve obscure challenges.

During the course of the contest, my performance became something of a talking point in the office. Colleagues occasionally stopped by my desk to appreciate how well I was doing in the CTF. Two much younger colleagues, both engineers I admired for their skill and professionalism, were discussing the results nearby. They were speaking softly, but I could still overhear parts of their conversation. Curious, I leaned slightly and listened a bit more carefully. I wanted to know what these two people, whom I admired a great deal, thought about my performance.

One of them remarked on how well I was doing in the contest. The other replied, 'Of course he is doing well. He has more than ten years of experience in C.' At that moment, I realised that no matter how well I solved those puzzles, the result would naturally be credited to experience. In my younger days, when I solved tricky problems, people would sometimes call me smart. Now it was expected. Not that I particularly care for such labels anyway, but it did make me realise how things had changed.

I was now simply the person with many years of experience, and solving challenges that involved dissecting binaries and solving technical puzzles was expected rather than remarkable. I continue to sharpen my technical skills to this day. While my technical results may now simply be attributed to experience, I hope I can continue to make a good impression through my professionalism, ethics and kindness towards the people I work with. If those leave a lasting impression, that is good enough for me.

Comments | #technology | #programming

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion