An analysis of why Peter Drucker's objectives-based management approach dominated American business culture despite W. Edwards Deming's more rigorous systemic philosophy that transformed Japanese industry.

At the heart of modern management theory lies a fundamental paradox: why did Peter Drucker's management-by-objectives philosophy become the dominant framework in American corporations, while W. Edwards Deming's more statistically rigorous approach remained largely confined to academic circles and Japanese manufacturing? The answer reveals uncomfortable truths about organizational complexity and human cognitive limitations.

Organizations, particularly large ones, present managers with what Lorin Hochstein aptly describes as a "big, hairy, complex mess."  This complexity grows exponentially with organizational size while managerial bandwidth remains stubbornly fixed. The modern manager, drowning in meetings and operational fires, faces an impossible task: making sense of systems whose interconnectedness defies simple comprehension.

This complexity grows exponentially with organizational size while managerial bandwidth remains stubbornly fixed. The modern manager, drowning in meetings and operational fires, faces an impossible task: making sense of systems whose interconnectedness defies simple comprehension.

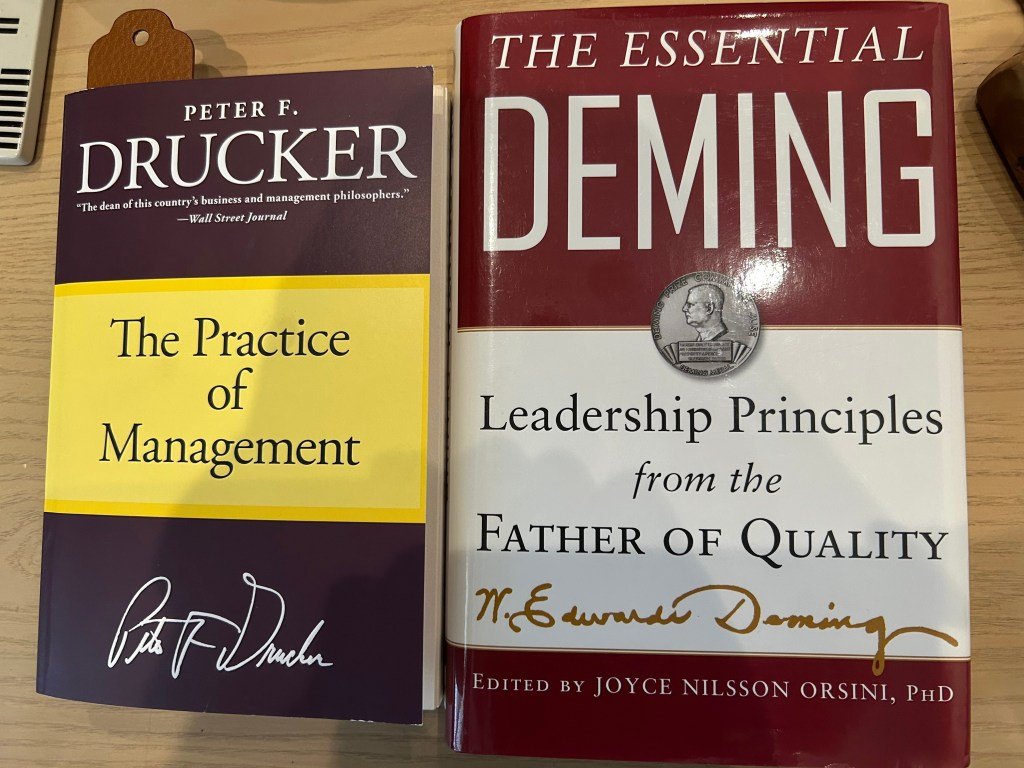

Drucker's genius lay in creating cognitive shortcuts for this overloaded reality. His Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) framework, popularized by John Doerr's book Measure What Matters,  provides precisely what overwhelmed executives crave: reductionism. By distilling organizational performance into a handful of quantifiable metrics, OKRs transform the "blooming, buzzing confusion" of operations into neat spreadsheets and dashboard visualizations. This filtering mechanism creates the illusion of control while minimizing cognitive load.

provides precisely what overwhelmed executives crave: reductionism. By distilling organizational performance into a handful of quantifiable metrics, OKRs transform the "blooming, buzzing confusion" of operations into neat spreadsheets and dashboard visualizations. This filtering mechanism creates the illusion of control while minimizing cognitive load.

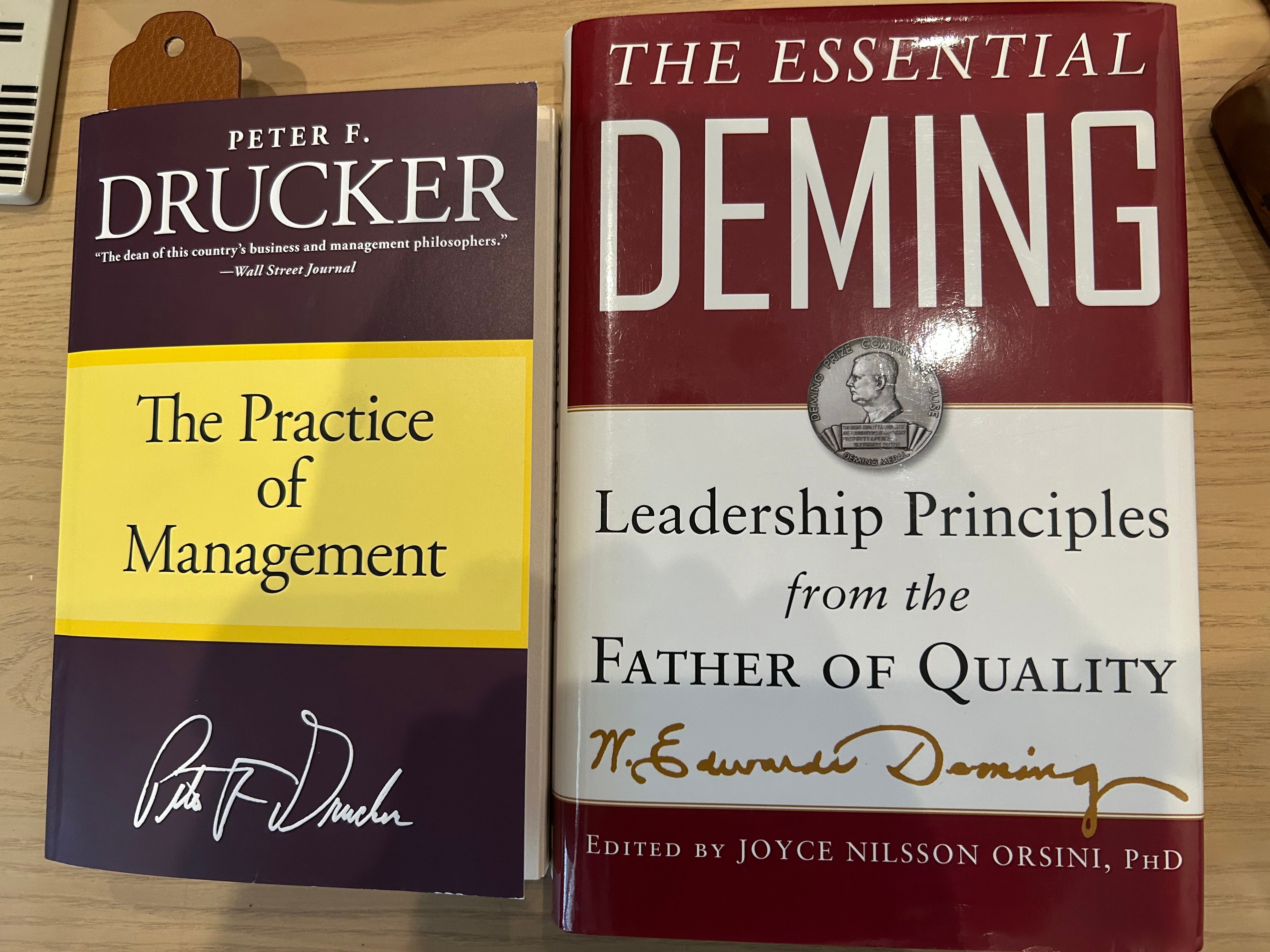

Deming's approach, articulated powerfully in his seminal work Out of the Crisis,  presents a philosophically opposite solution. Rather than simplifying complexity, Deming demanded deeper engagement with systems through statistical process control. His core premise—that meaningful improvement requires systemic understanding—stands in stark contrast to Drucker's target-setting. Deming famously categorized management by numerical targets as one of the "deadly diseases" of Western management, arguing that "if you don't change the system, the system doesn't change.

presents a philosophically opposite solution. Rather than simplifying complexity, Deming demanded deeper engagement with systems through statistical process control. His core premise—that meaningful improvement requires systemic understanding—stands in stark contrast to Drucker's target-setting. Deming famously categorized management by numerical targets as one of the "deadly diseases" of Western management, arguing that "if you don't change the system, the system doesn't change.

The distinction becomes clearest in their approaches to measurement. Drucker's OKRs resemble classical control systems like thermostats: set a desired temperature (objective) and measure deviation. Deming's statistical process control focuses instead on system variability—understanding why temperatures fluctuate even when the thermostat setting remains constant. While Drucker's method directs organizations toward targets, Deming's reveals whether the system is fundamentally capable of hitting them consistently.

Here lies the crux of Deming's failure in American business culture: his methodology transforms management into a continuous research program with unbounded informational demands. Where Drucker offers the comfort of bounded metrics, Deming insists that "the most important figures needed for management of any organization are unknown and unknowable" (quoting statistician Lloyd Nelson). This philosophical stance requires managers to embrace uncertainty and invest in deep systemic understanding—a proposition fundamentally at odds with the time-starved reality of corporate leadership.

The triumph of Drucker over Deming reflects the uncomfortable reality that organizational design often follows the path of least resistance. In Hochstein's formulation, Drucker makes management easier while Deming makes it harder—and when faced with this choice, human nature prevails. Yet this victory comes at a cost: organizations optimized for target-hitting often miss systemic flaws until they manifest as catastrophic failures. The recurring patterns of quality issues in manufacturing, technical debt accumulation in software, and operational fragility in complex systems all testify to the limitations of reductionist management.

While Deming's approach demands more from leaders, its emphasis on systemic understanding offers superior protection against catastrophic failure modes. The Japanese manufacturing revolution—with its Deming-inspired focus on continuous improvement (kaizen) and quality at the source—demonstrates the power of this philosophy. As organizations face increasingly complex challenges from distributed systems, AI integration, and global supply chains, the wisdom of Deming's systemic perspective may yet find its moment, forcing managers to embrace complexity rather than merely filtering it.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion