Despite six decades of research and technological advancement, lettuce harvesting remains stubbornly resistant to full automation due to complex technical requirements and unique economic factors.

Yuma, Arizona – While humanity has achieved moon landings and instant global shipping, the simple act of harvesting lettuce continues to defy full automation. This agricultural challenge persists despite over 60 years of concentrated effort, revealing fundamental limitations in robotics and AI when faced with biological variability.

The Historical Context

The quest for mechanization began in earnest after the termination of the Bracero Program in 1964. This government initiative had provided cheap Mexican labor for US farms, suppressing wages and removing economic incentives for mechanization. When the program ended, UC Davis quickly commercialized a tomato harvester for processing tomatoes – a success story  that created false hope for similar solutions in lettuce.

that created false hope for similar solutions in lettuce.

"Unlike tomatoes grown for processing, lettuce requires aesthetic perfection," explains agricultural technologist Rhishi Pethe. "Consumers demand flawless heads with specific cuts and trims that machines couldn't replicate with 1960s hydraulics and analog sensors."

The Current Stopgap: Harvest Aid Machines

Today's fields use sophisticated compromise systems. Slow-moving tractors pull conveyor wings where 20-25 workers cut, trim, and place lettuce heads. Key roles include:

- Cortadores (cutters): Select mature heads and make precise collar cuts

- Ojeros (quality controllers): Inspect produce on moving belts

- Reinas (packing coordinators): Ensure uniform bin filling

These systems reduce worker strain but still require human dexterity for critical tasks. Labor accounts for over 50% of production costs for specialty crops like lettuce and berries, creating constant pressure for automation.

Why Automation Eludes Us

Five key challenges explain the 64-year struggle:

Performance Requirements: Machines must process thousands of heads/hour while maintaining precise collar cuts. A single millimeter error renders heads unmarketable.

Economic Viability: Systems must demonstrate ROI against rising H-2A program costs ($25-$30/hour including housing). Transitioning from undocumented labor created new financial pressures.

Food Safety Integration: Equipment must comply with FSMA's Produce Safety Rule, requiring cleanable designs that prevent microbial contamination.

Quality Grading: Vision systems must detect subtle defects invisible to current sensors while handling variably shaped heads.

Environmental Demands: Machines must operate in predawn hours through dust, mud, and extreme temperature swings.

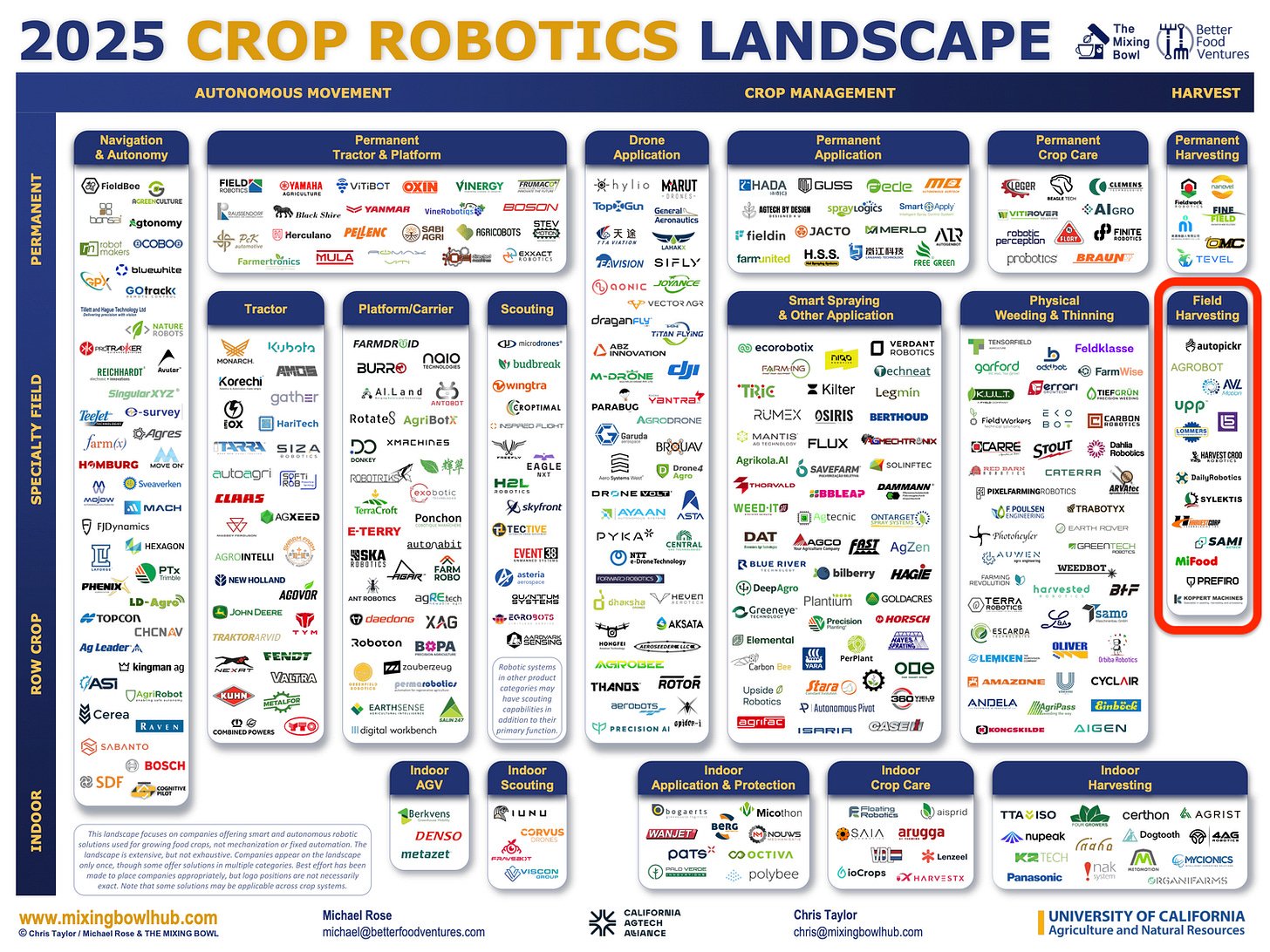

The Ecosystem Response

Yuma's agricultural technology hub demonstrates coordinated problem-solving:

- YCEDA (Yuma Center of Excellence for Desert Agriculture): Provides research assistance and test fields

- The Reservoir: Offers startup infrastructure and grower connections

- Axis Ag: Delivers technology services bridging developers and farmers

"This isn't about moonshot technology," notes Pethe. "It's about persistent iteration across mechanical engineering, computer vision, and agricultural science."

The Path Forward

Emerging technologies show promise: hyperspectral imaging for ripeness detection, force-sensitive robotic grippers, and reinforcement learning algorithms trained on thousands of harvest cycles. The economic driver remains clear: H-2A visa issuances grew from 50,000 (2010) to 370,000 (2025), making automation increasingly cost-competitive.

While lettuce harvesting may never achieve the glory of space exploration, solving this stubborn problem could yield something equally valuable: sustainable food production resilient to labor shortages and climate challenges.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion