An exploration of Emacs' notoriously complex text rendering system reveals why creating compatible GUI implementations demands radical pragmatism.

The ambition to create a GUI for an Emacs clone quickly confronts a formidable obstacle: GNU Emacs' intricate redisplay system. This rendering engine, responsible for translating buffer contents into visual representations, embodies decades of accumulated complexity that challenges modern implementation attempts. At its core lies a tension between historical design decisions and contemporary expectations of performance and functionality.

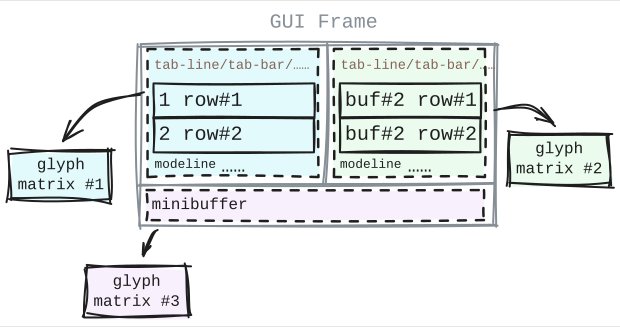

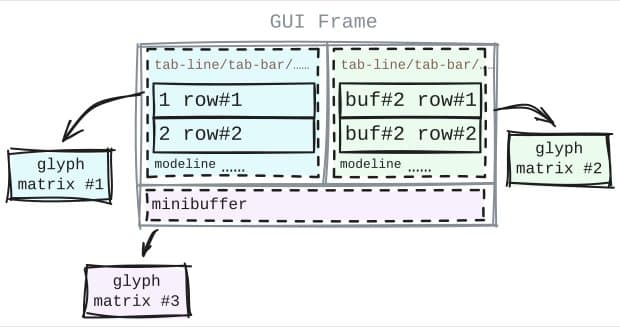

Central to Emacs' architecture is the glyph matrix structure, which orchestrates text layout across diverse environments—GUI windows, terminal frames, and nested buffer displays. This system must accommodate three critical text rendering challenges that collectively explain Emacs' substantial codebase (notably the 38,000-line xdisp.c).

First, bidirectional text rendering necessitates sophisticated handling of right-to-left scripts like Hebrew and Arabic. When processing the string "כוכב", the display engine must reverse character order dynamically—a process managed by 4,000 lines of dedicated bidi logic. This complexity persists despite Unicode standardization because Emacs implements its own algorithm rather than relying on external libraries.

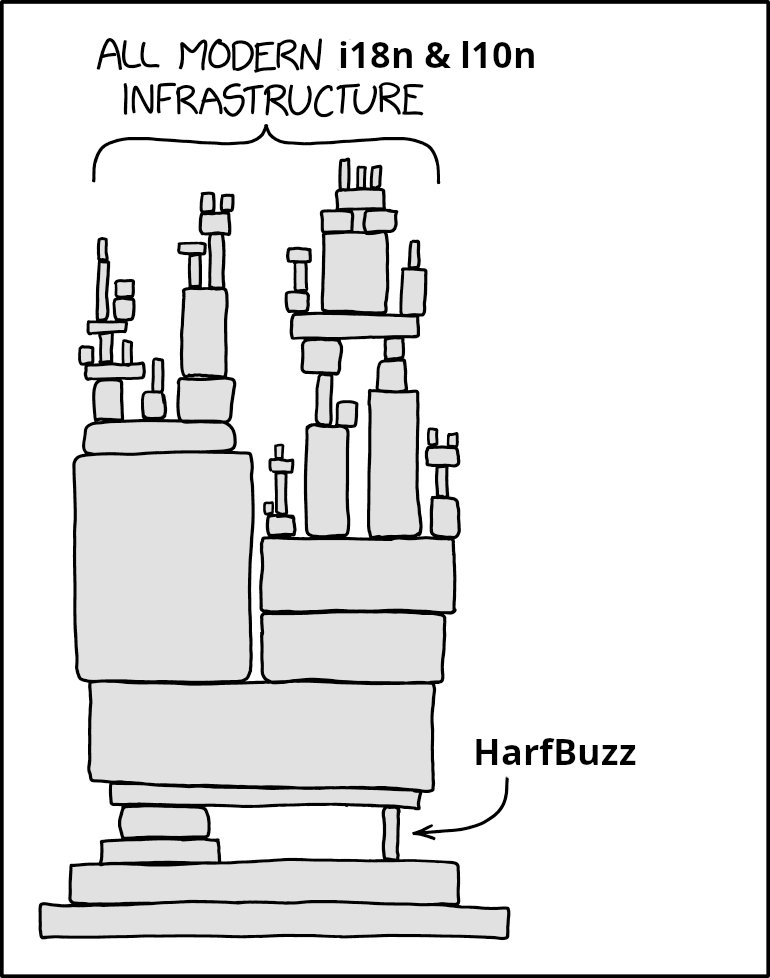

Second, ligature support requires deep font-processing capabilities. Arabic scripts demand contextual glyph composition where characters combine into single visual units. Emacs addresses this through the HarfBuzz library—a dependency so fundamental that it features in xkcd's famous "Dependency" meme. Crucially, Emacs extends this functionality through composition-function-table, allowing users to define custom glyph compositions via Lisp code.

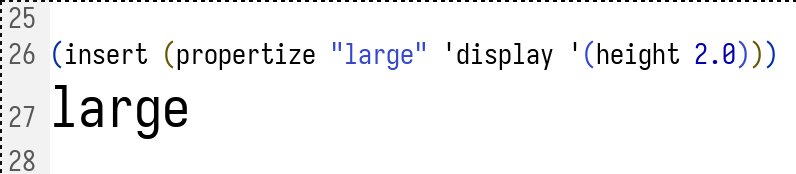

Third, text properties introduce computational flexibility at the cost of increased complexity. The display property enables runtime transformations where text segments can:

- Be replaced by alternative strings

- Render at dynamically calculated heights (

)

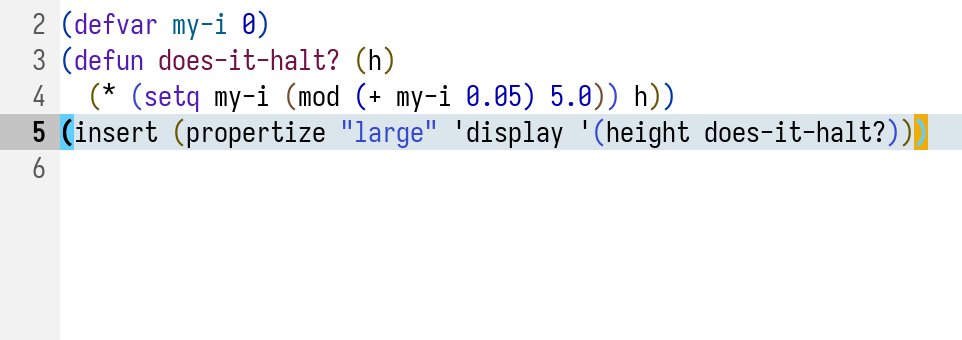

) - Execute functions during redisplay to determine visual properties (

)

)

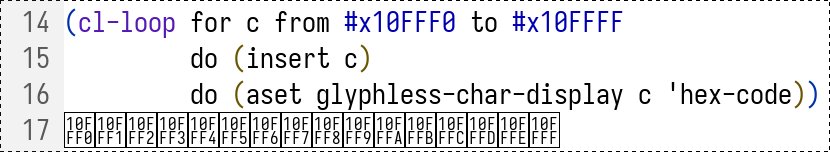

These capabilities create a Turing-complete styling system that intersects with other features like display tables (character substitution mappings) and glyphless-char-display controls ( ). The cumulative effect is a rendering pipeline where synchronous Lisp execution is deeply embedded in the display process.

). The cumulative effect is a rendering pipeline where synchronous Lisp execution is deeply embedded in the display process.

This architectural legacy clashes with modern expectations. Contemporary GUI implementations demand concurrent rendering to utilize multi-core processors, yet Emacs' design requires synchronous execution of display-related Lisp functions. Features like display tables—originally solutions for limited terminal capabilities—have diminishing relevance in Unicode-native environments. Meanwhile, user expectations have expanded to include image rendering and responsive interfaces during computation.

The pragmatic path forward acknowledges these tensions. Rather than attempting full compatibility, a viable approach prioritizes:

- Core text synchronization with property/overlay support

- Asynchronous handling of Lisp display functions

- Strategic omission of legacy features like composition-function-table

- Client-side rendering via RPC/IPC protocols

This minimal viable implementation embraces the reality that Emacs compatibility involves negotiating trade-offs between historical capabilities and contemporary constraints. By focusing on transport mechanisms rather than monolithic replication, new implementations can honor Emacs' spirit while acknowledging that some complexities reflect solutions to problems that have themselves evolved.

The journey toward functional Emacs-like GUIs remains less about replicating decades of accumulated solutions and more about rediscovering which principles remain essential in modern computational environments. As display technologies continue evolving, the most enduring tribute to Emacs may lie not in copying its implementation but in preserving its ethos of user-empowering flexibility through deliberately constrained modern interpretations.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion