MIT literature professor Joshua Bennett's new book "The People Can Fly" examines how Black prodigies like James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni, and others developed their talents, revealing the crucial role communities and institutions play in nurturing exceptional promise.

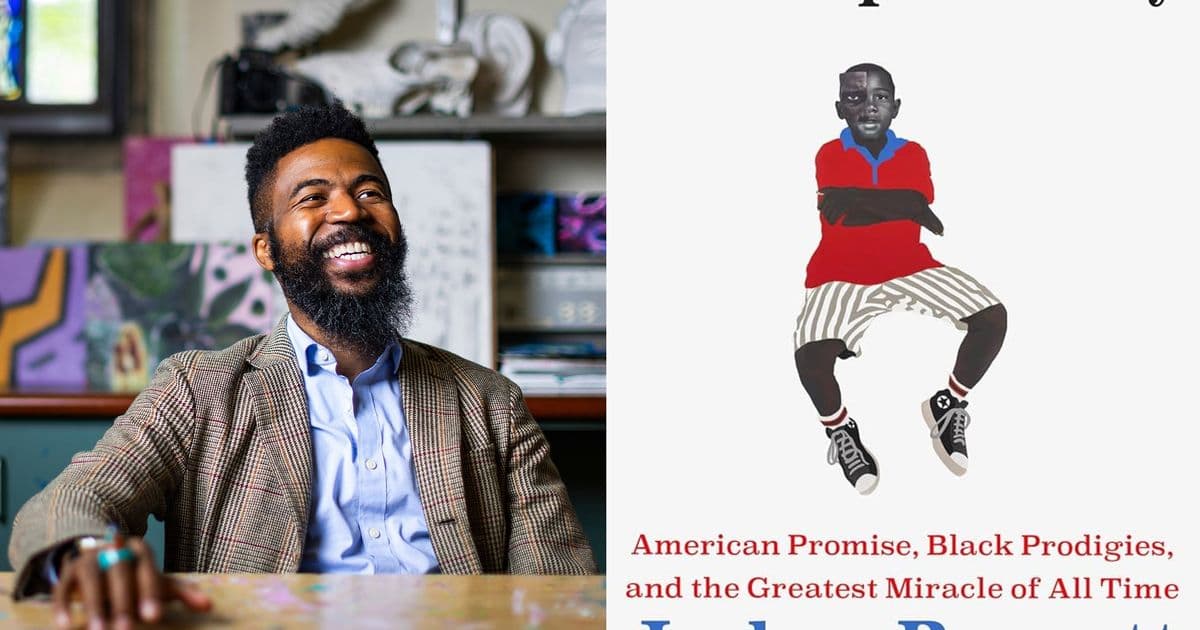

When we think of prodigies, we often imagine solitary geniuses whose talents seem to emerge fully formed. But MIT literature professor Joshua Bennett argues that this conception is fundamentally flawed. In his new book, "The People Can Fly: American Promise, Black Prodigies, and the Greatest Miracle of All Time," published this week by Hachette, Bennett examines how exceptional talent actually develops through community support, institutional cultivation, and persistent encouragement.

The Myth of the Self-Made Prodigy

Take James Baldwin, whose name is rarely associated with childhood precocity despite his remarkable early achievements. By age 14, Baldwin was already a successful church preacher, excelling in a role typically reserved for adults. He was reading Dostoyevsky by fifth grade, writing "like an angel" according to his elementary school principal, editing his middle school periodical, and contributing to his high school magazine. Yet Baldwin himself once declared he "had no childhood," and his work often elides these early details.

"We talk as if these people emerged ex nihilo," Bennett explains. "When all along the way, there were people who cultivated them, and our children deserve the same — all of the children of the world. We have a dominant model of genius that is fundamentally flawed, in that it often elides the role of communities and cultural institutions."

Reading Lives Through Literature

As both a literary scholar and poet, Bennett brings a unique approach to his biographical profiles. Rather than simply recounting facts, he carefully reads the works of these artists for indications about how they understood their own life trajectories. This method reveals how deeply their childhood experiences and social contexts shaped their creative visions.

For instance, Bennett finds in Baldwin's writings evidence of a "relentless introspection" as the young writer sought to understand his world. Even Baldwin's sole children's book, Bennett argues, contains "messages of persistence" that recognize every child's need for encouragement and education. The implication is clear: if someone as precocious as Baldwin still needed cultivation, then virtually everyone does.

Dreams of Flight and Space

One of the book's most compelling chapters examines poet Nikki Giovanni, whose work Bennett describes as filled with "space travel everywhere." From her most prominent poem, "Ego trippin' (there may be a reason why)," with its soaring imagery of someone "so hip even my errors are correct," to her broader body of work, Giovanni's writing reflects a fascination with cosmic exploration.

But this enthusiasm came with a critical edge. Giovanni publicly called for more opportunities for Americans from all backgrounds to become astronauts, recognizing that space exploration had been dominated by a particular slice of society. For her, the issue was making dreams achievable for more people — expanding "the orbit of their dreaming" to encompass whatever they needed.

Bennett connects this theme to a deeper cultural motif in Black history: stories and visions of flying. These narratives offer "a potent symbolism and a mode of holding on to a deeper sense that the constraints of this present world are not all-powerful or everlasting. The miraculous is yet available. The people could fly, and still can."

Family Dreams and Institutional Barriers

Throughout the book, Bennett emphasizes that behind many child prodigies are families and communities with their own dreams. He illustrates this through his own family history: growing up in Yonkers, New York, in the 1990s, he had a Princeton University sweatshirt inspired by "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air" and its character Uncle Phil, a Princeton alumnus.

"I would ask my Mom, 'How do I get into Princeton?'" Bennett recalls. "She would just say, 'Study hard, honey.' No one but her had even been to college in my family. No one had been to Princeton. No one had set foot on Princeton University's campus."

Yet Bennett's mother, the daughter of two sharecroppers who grew up in a tenement, had played at Carnegie Hall, earned a college degree, and bought her mother a color TV. Her vision proved powerful and persistent. Bennett ultimately earned his PhD from Princeton, demonstrating how one generation's dreams can become the next generation's reality.

A Broader Canvas of Promise

The book ranges across centuries of American history, from Phillis Wheatley — an enslaved woman whose 1773 poetry collection was later praised by George Washington — to Mae Jemison, the first Black female astronaut who enrolled at Stanford at age 16. Each profile reveals different aspects of how promise develops and what threatens it.

Bennett's work has already garnered praise from fellow artists. Lena Waithe, actor, producer, and screenwriter, calls it "a masterclass in literature and a necessary reminder to cherish the child in all of us."

The Universal Through the Individual

For Bennett, the key to understanding promise lies in examining individual lives. "It's part of what I tell my students — the individual is how you get to the universal," he says. "It doesn't mean I need to share certain autobiographical impulses with, say, Hemingway. It's just that I think those touchpoints exist in all great works of art."

By focusing on Black prodigies specifically, Bennett illuminates broader questions about American promise itself. What does it mean to cultivate talent in a society with unequal access to resources? How do communities sustain the dreams of their most gifted members? And what would it mean to truly believe that "the people can fly" — not just metaphorically, but in the sense that every child deserves the chance to develop their full potential?

As Bennett's mother might say: study hard, honey. The future belongs to those who dream it — and to the communities that help make those dreams possible.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion