New research reveals that a '2-random' cache eviction policy—selecting the least recently used of two randomly chosen lines—often outperforms traditional LRU in larger caches, with significant implications for hardware efficiency. This counterintuitive approach, inspired by mathematical load-balancing theories, offers near-optimal performance at lower implementation costs. The findings could reshape how developers and architects design high-performance systems.

Computer architecture professors have long whispered a surprising truth: random cache eviction isn't the performance disaster it seems. When a cache fills up, conventional wisdom dictates evicting the Least Recently Used (LRU) item, as recently accessed data is likely reused soon. But as Dan Luu's analysis reveals, LRU falters when workloads exceed cache capacity—a tight loop that doesn't fit cache causes misses on every iteration. Random eviction degrades more gracefully. The real breakthrough? Combining both approaches.

The 2-Random Revolution

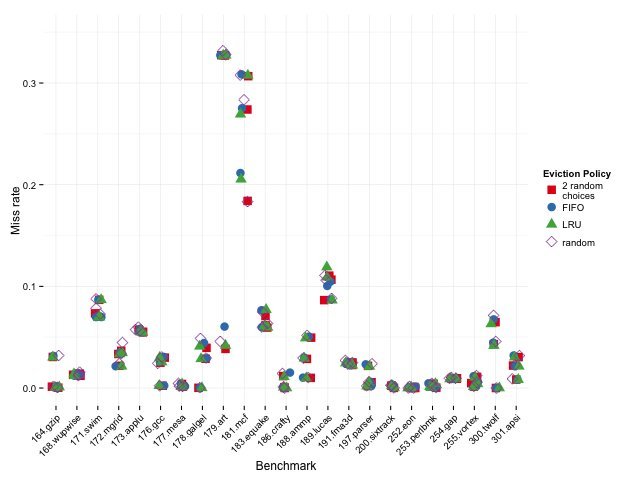

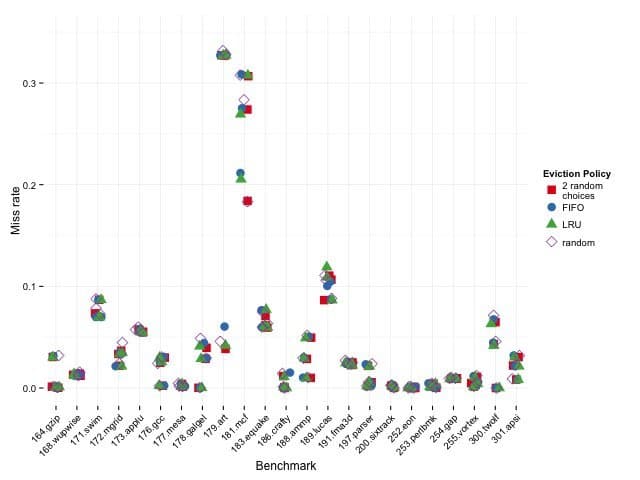

Lu's simulations using SPEC CPU benchmarks on a Sandy Bridge-like cache hierarchy (64K L1, 256K L2, 2MB L3) show that a "2-random" policy—picking two cache lines randomly and evicting the LRU between them—delivers striking results:

Caption: Relative miss rates for Sandy Bridge-like cache. Ratios show algorithm vs. random (lower is better). Source: Dan Luu

Caption: Relative miss rates for Sandy Bridge-like cache. Ratios show algorithm vs. random (lower is better). Source: Dan Luu

| Policy | L1 (64K) | L2 (256K) | L3 (2MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-random | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| LRU | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| Random | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Here, 2-random nearly matches LRU in smaller caches but pulls ahead in larger ones (L3), challenging assumptions about hierarchical cache behavior. As Luu notes, "LRU does worse than 2-random when miss rates are high, and better when miss rates are low."

Why Larger Caches Favor Randomness

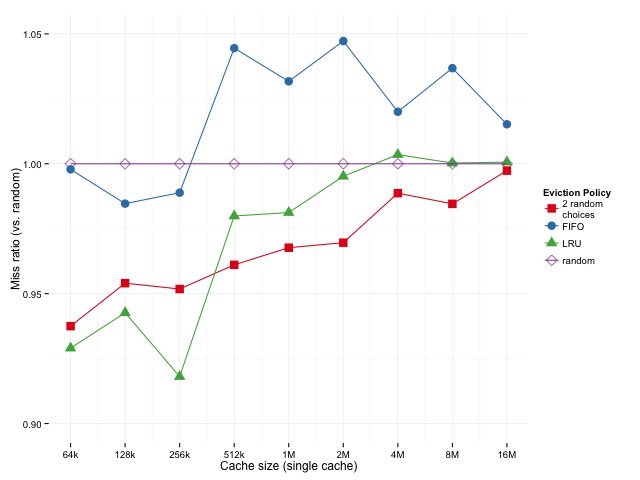

In hierarchical caches, L3 rarely sees active lines (already held in L1/L2), making LRU's recency tracking less effective. Sweeping cache sizes from 512KB to 16MB confirms 2-random's advantage scales with capacity:

Caption: Geometric mean miss ratios for varying cache sizes. Source: Dan Luu

Caption: Geometric mean miss ratios for varying cache sizes. Source: Dan Luu

The trend holds even with "pseudo-random" approximations (80% accurate), where pseudo-3-random—evicting the LRU of three random choices—closes the gap with true 2-random. This is critical for real hardware, as true LRU is often prohibitively expensive.

The Math Behind the Magic

The efficacy stems from the "power of two random choices" principle, documented by Mitzenmacher et al. Randomly distributing items (like cache lines) risks uneven loads, but selecting the best of two random options slashes imbalance from O(log n) to O(log log n). This theory has revolutionized load balancing and now cache design.

Practical Implications

- Cost Efficiency: 2-random requires similar hardware to pseudo-LRU but outperforms it in large caches, offering a free lunch for architects.

- Beyond CPUs: The approach applies to databases, CDNs, and any cache-reliant system.

- Future Work: Hybrid policies (e.g., LRU for L1/L2, 2-random for L3) or higher-k variants could unlock further gains.

As cache hierarchies grow to tackle data-intensive workloads, embracing controlled randomness might be the key to avoiding costly misses—proving that sometimes, two choices are better than one.

Source: Analysis based on Dan Luu's research using dinero IV simulations and SPEC CPU traces.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion