While semiconductors dominate modern electronics, the vacuum tube—a technology that manipulated electrons in evacuated glass tubes—built an enormous technological ecosystem in the first half of the 20th century. Its legacy persists in surprising places, from microwave ovens to fusion reactors, demonstrating how foundational technologies can evolve into specialized niches long after their mainstream decline.

The narrative of technological progress often follows a simple arc: a revolutionary invention emerges, rapidly improves, and is eventually replaced by a superior successor. For electronics, this story centers on the transistor and the semiconductor revolution that followed. Yet this linear progression obscures a more complex reality. The vacuum tube, the technology that preceded the transistor, did not simply vanish. Instead, it fragmented into a diverse family of devices, each finding its own enduring niche. The tube's story is not one of obsolescence, but of specialization and persistence.

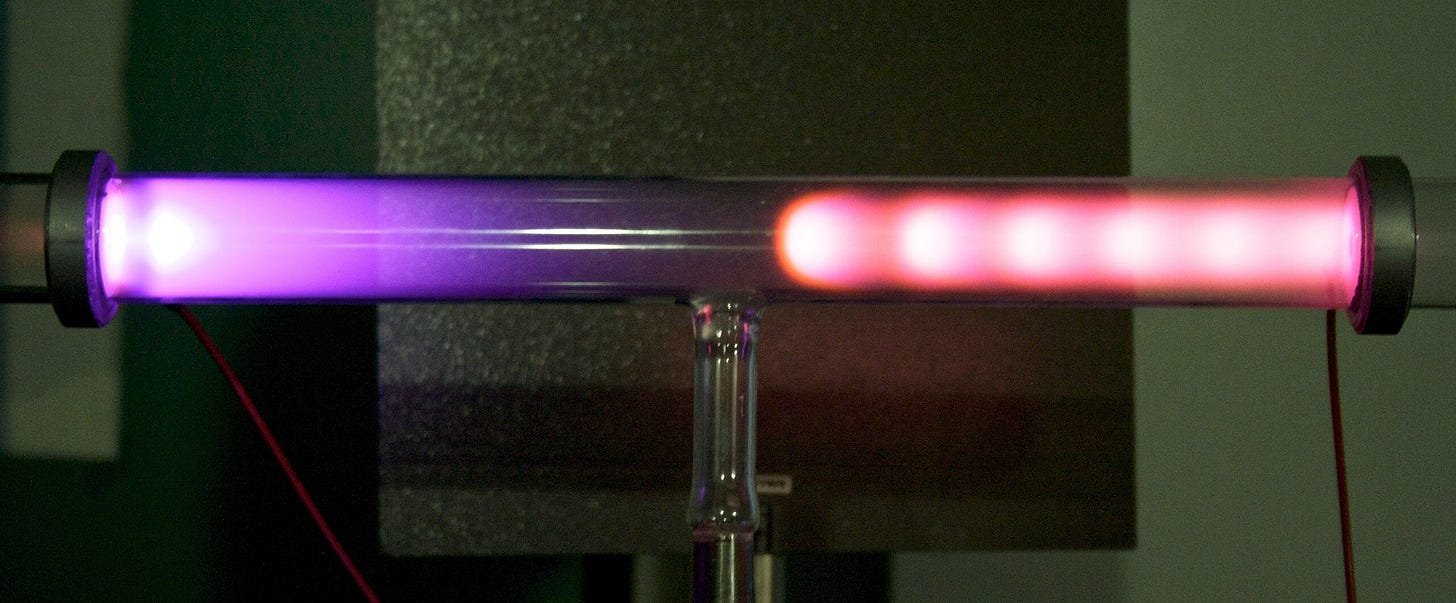

The vacuum tube's origins lie in two parallel lines of 19th-century scientific inquiry. The first was the study of gas discharge tubes, where electricity passed through rarefied gas produced a mysterious glow. Early experiments by Faraday and Plücker, using tubes from instrument maker Heinrich Geissler, revealed cathode rays—later understood to be streams of electrons. These "Crookes tubes" became essential tools for fundamental physics, leading directly to the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Roentgen and the identification of the electron by J.J. Thomson. The second line was the development of incandescent lighting. Thomas Edison's practical light bulb in 1879, achieved through a superior vacuum, inadvertently revealed the "Edison Effect": current flowing from a hot filament to a separate metal plate. This phenomenon, understood decades later as thermionic emission, was the key principle that would enable the vacuum tube's electronic applications.

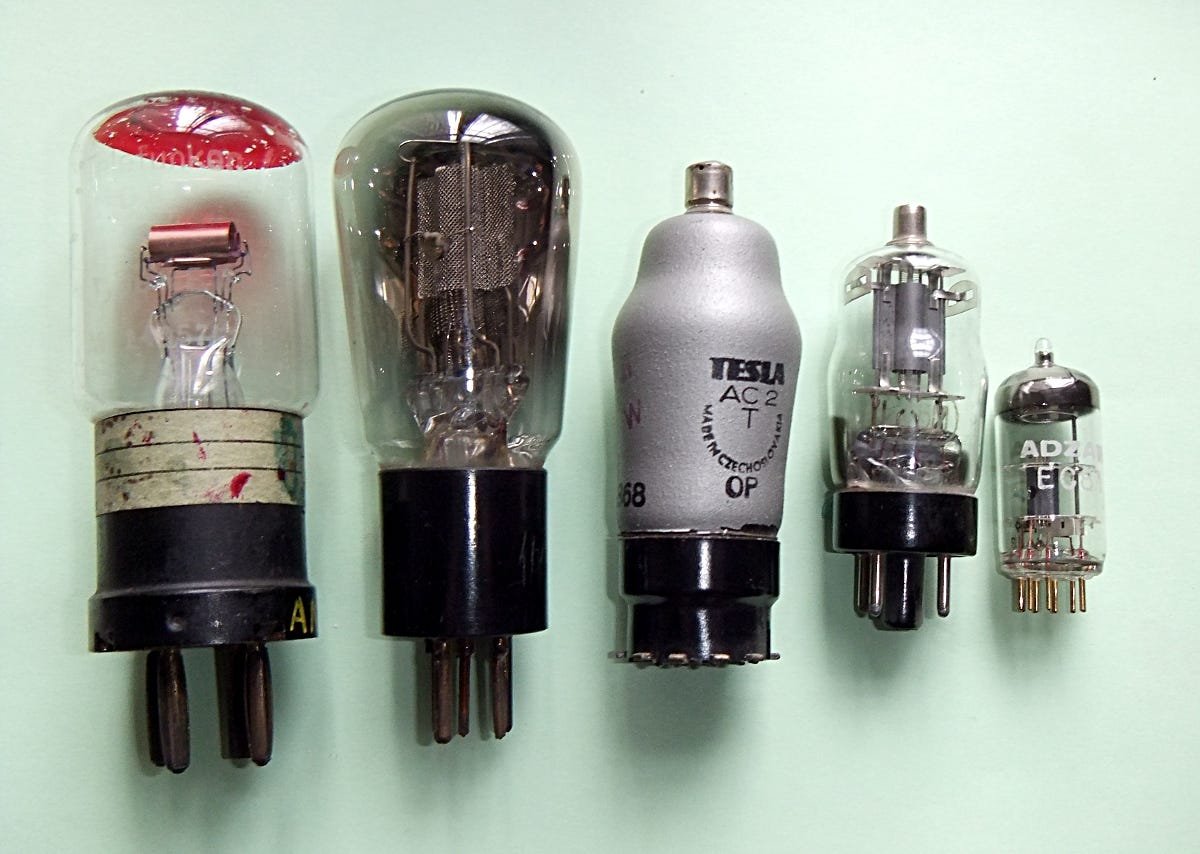

The convergence of these two strands at the turn of the 20th century sparked an explosion of innovation. John Fleming harnessed the Edison Effect to create the Fleming Valve (1904), a diode that rectified alternating current for early radios. The pivotal moment came when Lee de Forest added a third element—a control grid—to create the Audion. Though de Forest himself misunderstood its operation, AT&T scientists recognized its amplifying potential, refining it into the reliable triode. This single device unlocked a cascade of applications: it made transcontinental telephone calls feasible, powered the first radios and televisions, and formed the logic circuits of early computers like ENIAC, which used 18,000 vacuum tubes. By the late 1920s, AT&T's telephone system alone contained over 100,000 tubes.

Simultaneously, Ferdinand Braun's cathode ray tube (CRT), developed to measure high-frequency currents, became the foundation for electronic displays. The CRT's ability to steer a beam of electrons with magnetic fields made it ideal for oscilloscopes and, crucially, for television. For decades, CRTs were the heart of TV sets, both as camera tubes and display screens, until flat-panel displays and CMOS sensors took over. The CRT's principle also spawned the first electron microscopes and early computer memory systems (Williams tubes).

The gas discharge tube, the other progenitor, also diversified. The discovery of neon in 1898 led to neon lighting, while other gases gave rise to mercury vapor, fluorescent, and sodium vapor lamps. Beyond illumination, gas discharge tubes evolved into thyratrons, capable of handling high currents for industrial switching, and the tiny plasma cells that formed the pixels of plasma televisions. They are also integral to Geiger counters, surge protectors, and carbon dioxide lasers.

Perhaps most surprisingly, vacuum tubes became generators of electromagnetic radiation beyond visible light. Roentgen's accidental X-ray discovery led to modern X-ray tubes. In the 1920s, General Electric's magnetron, initially an electronic switch, was found to emit microwaves. The British cavity magnetron, a WWII development, enabled airborne radar and later found a permanent home in the microwave oven. The klystron, another tube-based microwave emitter, provides power for particle accelerators like SLAC and radiation therapy machines. Even more exotic, gyrotrons generate the high-frequency radiation needed to heat plasma in fusion energy experiments.

The scientific impact of this ecosystem was profound. Four Nobel Prizes were directly awarded for discoveries made using vacuum tube devices: Roentgen's X-rays, Thomson's electron, Ernst Ruska's electron microscope, and Owen Richardson's work on thermionic emission. The indirect impact was larger still, as vacuum tubes powered countless instruments and drove research that led to further breakthroughs, such as Bell Labs' first Nobel Prize for electron diffraction.

The vacuum tube's history challenges the simplistic model of a single technology being wholly replaced. Instead, it illustrates a "Cambrian explosion" of specialization. The core principle—controlled electron flow in a vacuum or gas—was adapted into a vast array of devices, each advancing along its own S-curve. While many applications (like general computing and consumer radios) were indeed supplanted by semiconductors, the tube's descendants remain vital in high-power, high-frequency, and extreme-condition niches where solid-state technology still struggles. The magnetron in your microwave, the klystron in a cancer treatment machine, and the gyrotron in a fusion reactor are all direct descendants of those early glass tubes. The vacuum tube didn't die; it evolved, retreating to the specialized frontiers where its unique capabilities remain unmatched.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion