Building a custom programming language serves as a profound technical education that deepens understanding of computing fundamentals while offering creative fulfillment through deliberate design choices and incremental implementation.

For many software developers, programming languages exist as utilitarian tools—black boxes whose internal mechanics remain abstracted away beneath layers of syntax and standard libraries. Yet as thesephist.com articulates in a reflective treatise on language creation, the deliberate construction of an interpreter or compiler constitutes one of the most intellectually transformative projects an engineer can undertake. This endeavor forces confrontation with computing's foundational layers: memory allocation strategies, parsing algorithms, type system implementations, and execution models that collectively illuminate how abstract code manifests as concrete computation.

The primary value lies not in producing production-ready tools—though that may occur—but in cultivating systems thinking. Designing a language requires navigating cascading tradeoffs: Should memory management be manual or garbage-collected? How should error handling propagate? What primitives belong in the core language versus standard libraries? Such questions demand engagement with computer science's theoretical underpinnings, from graph theory in optimization passes to category theory in type system design. Crucially, this knowledge transfers laterally; developers report heightened proficiency in their primary work even when unrelated to compilers, thanks to refined mental models of data flow and execution environments.

A successful language project begins with constrained vision rather than boundless ambition. Rather than attempting an omnipotent "ultimate language," the author advocates selecting specific computational concepts for deep exploration—perhaps immutable data structures, C interoperability, or macro-based metaprogramming. This focus yields richer learning than superficial feature aggregation. Historical languages offer particularly fertile ground: Lua's coroutines and tables, APL's array-oriented paradigm, Lisp's homoiconicity, and Forth's stack-based execution all represent distinct points in the design space worth examining. Semantics—how the language behaves—deserve precedence over syntactic preferences, as they prove harder to retrofit later.

Implementation follows a test-driven design rhythm. Before writing parser code, authors should draft sample programs using imagined syntax, validating whether core ideas facilitate expressive solutions. Does a functional-reactive approach simplify network servers? Can error values integrate cleanly with control flow? This prototyping phase surfaces design flaws early, when corrections remain inexpensive.

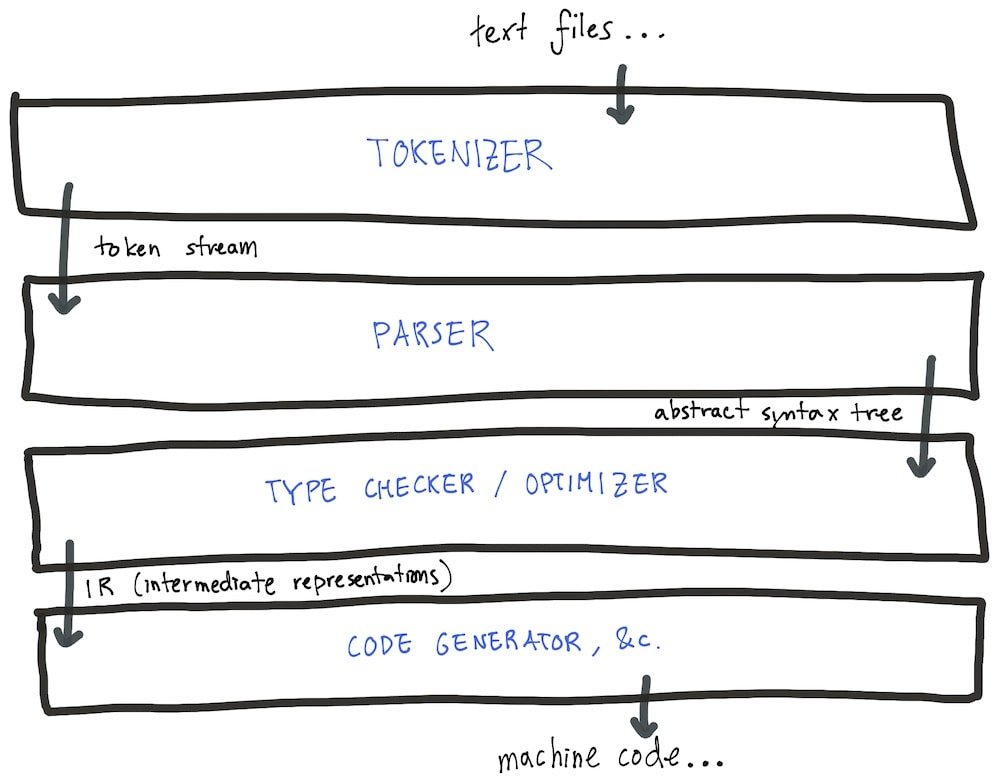

Actual construction involves stratified transformations: source text becomes tokens; tokens form abstract syntax trees; trees generate intermediate representations; finally, execution occurs via interpretation or compiled machine code. Resources like Crafting Interpreters and Let's Build a Simple Interpreter provide structured pathways through these stages, while deeper dives await in advanced texts like Writing an Interpreter in Go. Studying exemplary implementations proves equally instructive—the Lua C source reveals elegant virtual machine design, while Wasm3 demonstrates innovative WebAssembly interpretation strategies.

Post-minimum-viable-language, expansion opportunities abound: adding gradual typing, just-in-time compilation, or foreign function interfaces. Each extension deepens engagement with computer science frontiers—type theory when implementing generics, low-level binary protocols during C interop, or speculative optimization for JITs. Crucially, these become lifelong learning vectors rather than finite tasks; a language project evolves alongside its creator's curiosity.

Counterarguments rightly note that most developers needn't build languages professionally. Yet dismissing the exercise as impractical overlooks its pedagogical superpower: No other project so comprehensively traverses the computing stack while rewarding creative expression. By starting modestly—perhaps implementing a domain-specific calculator or Lisp subset—and progressively incorporating sophisticated features, developers gain not just compiler-writing skills but architectural wisdom applicable across software engineering's entire spectrum. The journey demystifies computing's inner magic while proving that with deliberate design and incremental construction, any programmer can forge their own tools for thought.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion