In Manhattan's Turtle Bay neighborhood, forgotten composer Michael Brown and his wife Joy provided Harper Lee with a year's salary that enabled the creation of 'To Kill a Mockingbird', an uncelebrated act of patronage that reshaped 20th-century literature from an unlikely artistic enclave.

Manhattan's Turtle Bay neighborhood presents a palimpsest of American history. This wedge of land between 43rd and 53rd Streets, bookended by the East River and Lexington Avenue, layers Dutch farmland beneath British Revolutionary headquarters, industrial slaughterhouses below diplomatic missions. Yet its most enduring legacy emerged from an unexpected artistic enclave that flourished mid-century, where Broadway composers and corporate lyricists formed a creative crucible. Within this ecosystem, at 153 East 50th Street, composer Michael Brown and his wife Joy performed an act of quiet patronage that would alter the course of American literature.

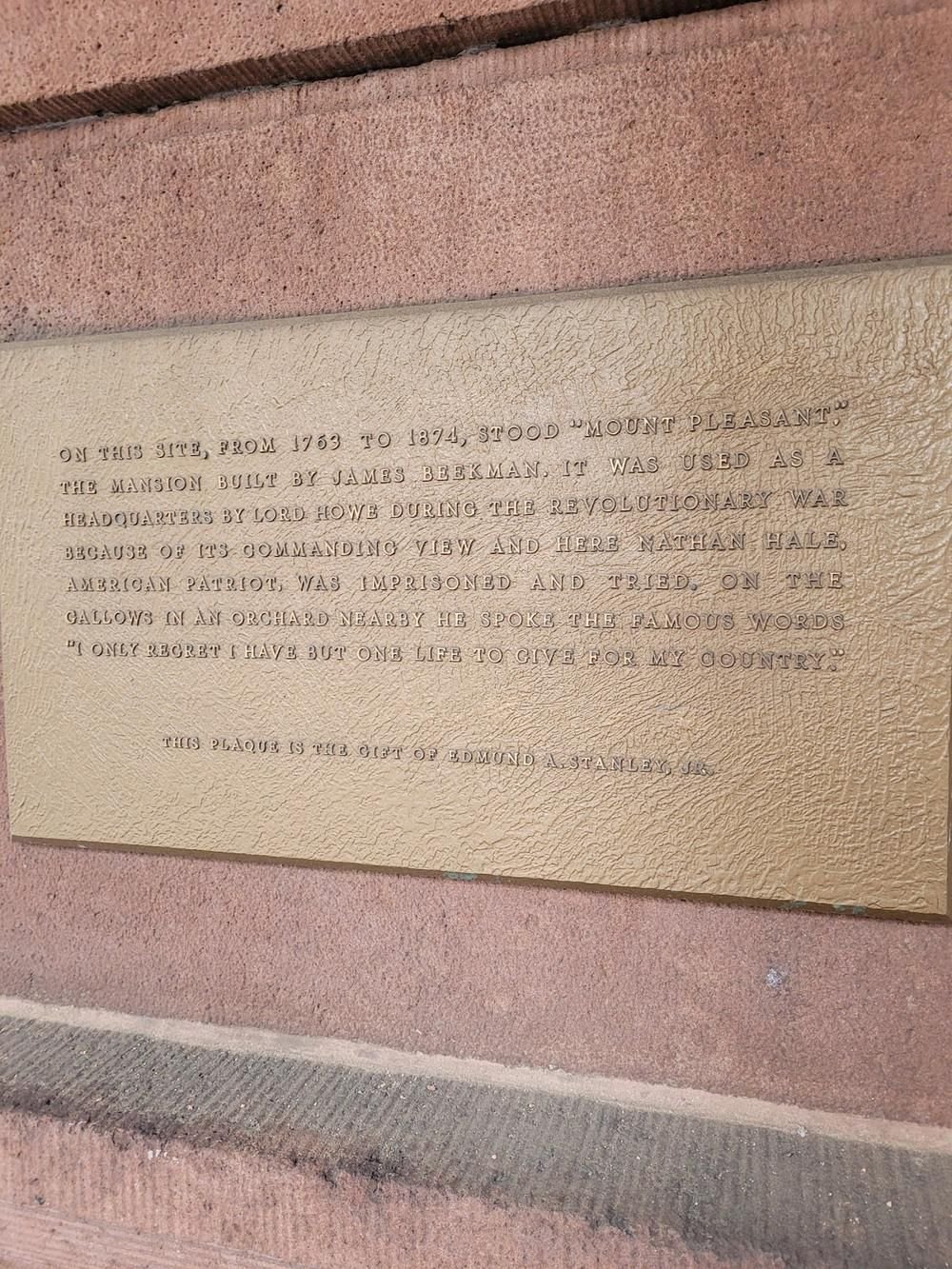

The plaque commemorating Nathan Hale's execution stands just blocks from where literary history was quietly made. (Photos by Andrew Egan)

The plaque commemorating Nathan Hale's execution stands just blocks from where literary history was quietly made. (Photos by Andrew Egan)

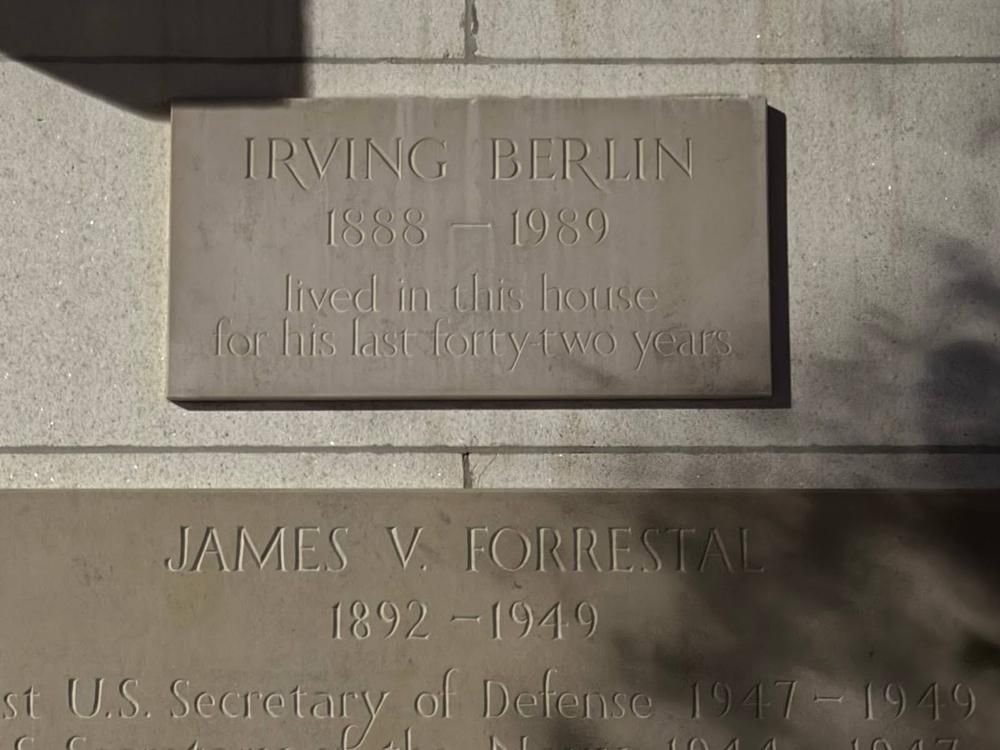

The neighborhood's artistic credentials were already formidable. From 1947 to 1989, Irving Berlin resided nearby, penning "White Christmas" and "Puttin' on the Ritz" within earshot of Cole Porter's Waldorf Towers piano. Stephen Sondheim purchased his 49th Street townhouse with "Gypsy" royalties, dubbing it "the house that Gypsy built." This concentration wasn't accidental. Turtle Bay offered suburban tranquility amid Manhattan's bustle, with ten-minute walks to Broadway theaters and natural gathering spaces for artists. "The proximity to peers created a creative petri dish," observes Broadway historian Ken Bloom. "They fed each other ideas over martinis in living rooms that doubled as salons."

Into this world stepped Michael Brown. The Texas-born composer arrived in 1946 after Army service, carving a niche in an unusual theatrical genre: industrial musicals. Corporations like DuPont and Electrolux commissioned lavish Broadway-style productions to motivate employees, with budgets reaching $3 million—six times typical Broadway costs. Brown's lyrics for "Love Song to an Electrolux" celebrated domestic appliances with Cole Porter-esque wit: "This is the perfect matchment / All sweet and serene. / I’ve formed an attachment / I’m in love with a lovely machine." His 1964 World's Fair spectacle "Wonderful World of Chemistry" ran 17,000 performances—still surpassing "Phantom of the Opera's" record.

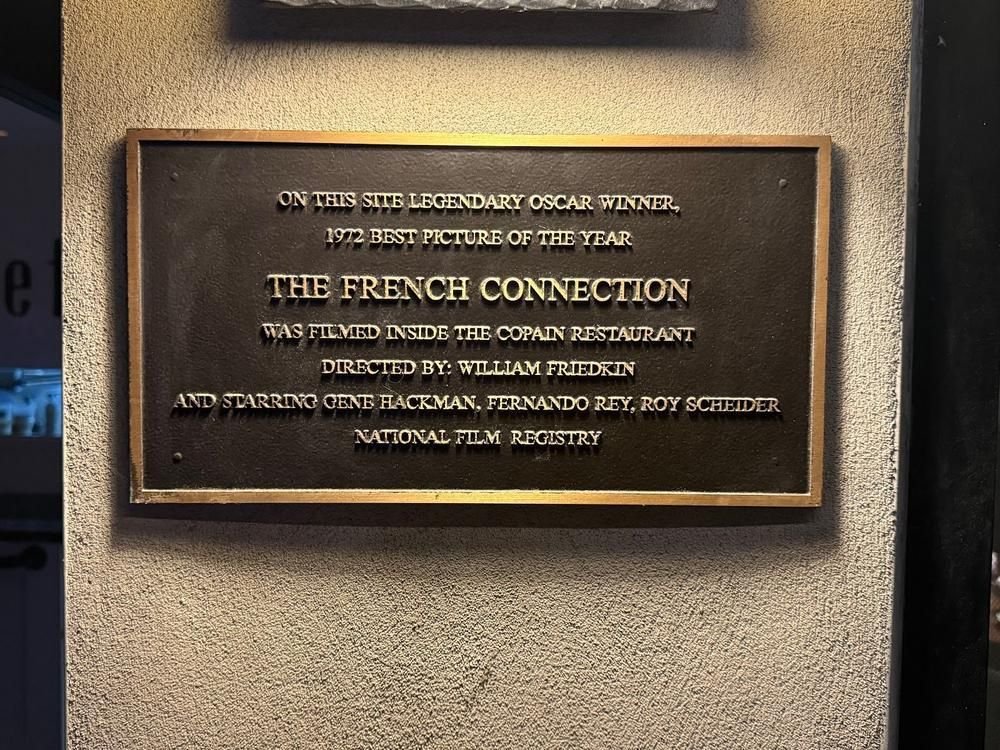

Turtle Bay's plaques typically commemorate film history, like this French Connection marker, rather than literary turning points.

Turtle Bay's plaques typically commemorate film history, like this French Connection marker, rather than literary turning points.

The Browns' townhouse became a hub for artistic gatherings. At one dinner, they met Harper Lee—then an airline reservations clerk struggling to write between shifts. Truman Capote, Lee's childhood friend, had introduced them to Manhattan's literary circles. Recognizing her talent, the Browns made an extraordinary Christmas gift in 1956: an envelope containing a year's salary with the note "You have one year off from your job to write whatever you please." Lee recalled trembling hands opening the envelope, later writing: "I went to the bathroom and locked the door and sat on the edge of the tub and wept."

What followed became publishing legend. Lee used the reprieve to complete "To Kill a Mockingbird," undergoing multiple revisions before its 1960 publication. When Joy Brown heard the initial print run was 5,000 copies, she gasped: "Who in the world is going to buy 5,000 copies?" The novel would sell 30 million copies worldwide, win the Pulitzer Prize, and become required reading in American classrooms. The Browns insisted their support remain private for fifty years, with Lee describing it as "a fantastic gamble" that Michael Brown countered with conviction: "No honey. It’s not a risk. It’s a sure thing."

The irony lies in Turtle Bay's commemorative landscape. Plaques dot every block—honoring Nathan Hale's disputed execution site, Irving Berlin's residence, even filming locations for The French Connection. Yet no marker acknowledges where American literature's most consequential patronage occurred. This omission reflects broader tensions about how cities memorialize creativity. "We plaque battles and buildings," notes urban historian Samuel Riggs, "but rarely the fragile ecosystems that enable art. The Browns' townhouse was as vital as any theater."

Why does this quiet corner of literary history matter? Beyond gifting the world a seminal novel, it reveals how artistic legacies are built: not just through solitary genius, but through community support and financial risk-taking. The industrial musicals that funded Brown's career—those curious corporate extravaganzas—became unwitting patrons to Harper Lee. Without Turtle Bay's concentration of artists, the introduction might never have occurred. Without mid-century corporate America's peculiar investment in song-and-dance employee motivation, the Browns couldn't have funded Lee's year of writing.

Today, as algorithms dictate creative patronage and neighborhoods lose artistic density, the Browns' model feels almost subversive. Their townhouse stands as testament to a time when commerce indirectly funded culture, when artists lived in walking distance of collaborators, and when faith in talent could be packaged in a Christmas envelope. The unmarked building on East 50th Street reminds us that literature's most enduring monuments aren't always made of stone—sometimes, they're built from trust, proximity, and the courage to bet on an unknown writer.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion