What began as a routine investigation into rare brain disease cases in Canada's New Brunswick province evolved into a contested medical mystery involving 500 patients, conflicting scientific conclusions, and allegations of systemic failure.

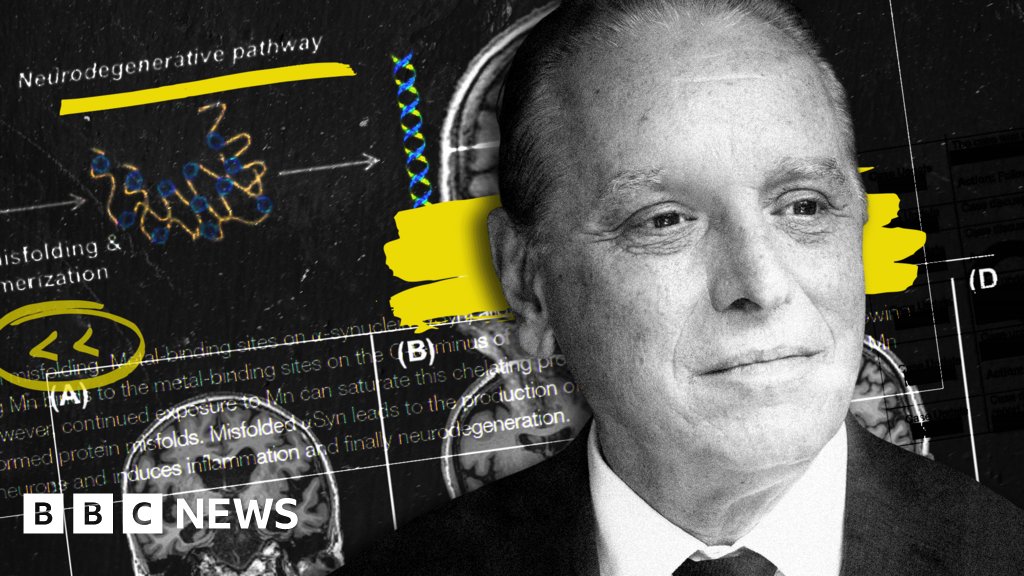

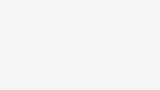

In early 2019, neurologist Dr. Alier Marrero alerted Canadian health authorities about something unusual unfolding in New Brunswick. What started as concern over two potential Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) cases revealed a pattern Marrero had observed for years: patients exhibiting rapidly progressing neurological symptoms with no identifiable cause. Initial tests ruled out CJD, leaving Marrero perplexed as his patient list grew from 20 cases to 48, then ballooned to 500 over five years.

The symptoms formed a bewildering constellation: dementia in young adults, muscle atrophy, unexplained pain, hallucinations, and Capgras delusion – where patients believe loved ones have been replaced by imposters. Marrero documented cases where patients forgot basic skills like writing letters, while others experienced sensory distortions where cold water felt scalding. "I kept seeing new patients, documenting new cases, and seeing new people dying," Marrero recalled. "An image of a cluster became more clear."

Many patients pointed to environmental toxins as the culprit. Marrero noted seasonal symptom spikes coinciding with forestry herbicide spraying, focusing suspicion on glyphosate – a chemical linked in some studies to neuroinflammation. Forest NB, representing the forestry industry, maintains glyphosate use complies with regulations and poses no expected risks. When Marrero reported elevated glyphosate and heavy metal levels in patients, provincial officials didn't pursue industrial exposure theories despite federal scientists' initial enthusiasm.

In 2021, Canada's federal health research agency offered New Brunswick CA$5 million to investigate. Simultaneously, the Mind Clinic opened with Marrero leading specialized care for cluster patients. Yet provincial officials abruptly declined the funding and suspended federal collaboration. Patient advocate Kat Lanteigne interprets this as obstruction: "They pulled the plug because they don't want anybody looking. Full stop." Internal emails reveal federal scientists initially found the cluster compelling – one called it "like reading a movie script" – but provincial concerns about Marrero's methodology grew.

Jillian Lucas embodies the human toll. After her stepfather Derek Cuthbertson developed sudden rage and cognitive decline, Marrero diagnosed him with the mystery syndrome. Lucas soon developed her own symptoms: tremors, speech difficulties, and distorted temperature perception. Though fiercely loyal to Marrero, her condition deteriorated to where she now contemplates medical assistance in dying (MAID). "I have a limit in my mind of how far I can go," Lucas said from her home, where she spends 90% of her time in one room. Her MAID application lists "degenerative neurological condition of unknown cause" as justification – accepted without definitive diagnosis under Canada's laws.

The province's subsequent investigations concluded no mystery disease existed. A 2025 JAMA Neurology paper by independent researchers examined 25 cases (including autopsies) and found all had explainable conditions like frontotemporal dementia or functional neurological disorder (FND). The study attributed the cluster to misdiagnosis, pandemic-fueled distrust, and media amplification. Lead author Dr. Anthony Lang stated: "What we have here is a case of misdiagnosis evolving to misinformation, resulting in suffering."

Yet patient experiences diverge sharply. Sandi Partridge accepted her FND diagnosis after leaving Marrero's care: "I hit every single marker." Conversely, Gabrielle Cormier – diagnosed by Marrero at 18 – rejected Toronto specialists' FND conclusion despite becoming wheelchair-dependent. Her family alleges Lang violated privacy by including her anonymized data in his study without consent, a claim he disputes.

Marrero now treats over 500 patients outside the provincial system, operating from his Moncton home. He faces criticism for excessive testing and unconventional treatments but retains patient devotion. Neuropathologist Dr. Gerard Jansen, who examined eight autopsies finding only known diseases, goes further: "These patients are being abused." Yet no formal complaints against Marrero exist. As one official noted: "All his patients love him."

With an upcoming provincial report promising analysis of toxin claims, patients await validation or closure. For Lucas and others considering MAID, time is the scarcest resource. "The answer cannot be nothing," Lanteigne insists. As Marrero maintains his solitary pursuit of answers, New Brunswick's neurological enigma remains suspended between unexplained suffering and the limitations of medical science.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion