Discover how to implement interactive programming in C using shared library reloading. This technique, popularized by game developers, allows modifying running programs without restarts, dramatically speeding up iteration cycles. Learn the constraints and design patterns to make it work, complete with a practical Game of Life example.

For developers accustomed to dynamic languages like JavaScript or Lisp, the idea of modifying a running program feels natural. But in C? Traditionally, changing logic meant recompiling and restarting—until now. A technique leveraging shared library reloading brings interactive programming to C, revolutionizing development workflows for games, simulations, and long-running applications.

The Shared Library Secret

The core insight is simple yet transformative: build your application's logic as a shared library (.so on Linux, .dll on Windows). A lightweight "wrapper" executable loads this library, monitors it for changes, and hot-swaps it at runtime. As Chris Wellons explains, this approach—pioneered in Casey Muratori's Handmade Hero series—eliminates the restart penalty during development.

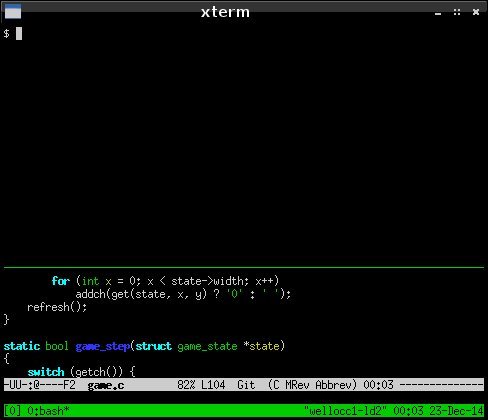

Live-updating C code in a Game of Life simulation (Credit: nullprogram.com)

Live-updating C code in a Game of Life simulation (Credit: nullprogram.com)

Critical Constraints and Design Patterns

This power comes with constraints:

- No Global State: Static/global variables vanish on reload. The library must store all state in heap-allocated structs passed by the wrapper.

- Function Pointer Pitfalls: Pointers to functions within the library become invalid after reload. Solutions require careful architectural design.

- Standard Library Caution:

malloc()and other stdlib functions may introduce hidden state. Minimal external dependencies are ideal.

A well-defined API struct bridges the wrapper and library:

struct game_api {

struct game_state *(*init)();

void (*finalize)(struct game_state *state);

void (*reload)(struct game_state *state);

void (*unload)(struct game_state *state);

bool (*step)(struct game_state *state);

};

The wrapper only interacts via this struct, calling init(), step(), and lifecycle hooks like reload() after a swap.

The Reloading Machinery

On Unix-like systems, dlopen(), dlsym(), and dlclose() handle the heavy lifting. The wrapper:

- Tracks the library's inode (not modification time) to detect changes.

- Calls

unload()(if defined), thendlclose()the old handle. - Loads the new library with

dlopen(), fetches thegame_apistruct viadlsym(). - Invokes

reload()for library-specific reinitialization.

A minimal main loop:

int main(void) {

struct game game = {0};

for (;;) {

game_load(&game); // Reload if library changed

if (game.handle && !game.api.step(game.state)) break;

usleep(100000); // 100ms delay

}

game_unload(&game);

return 0;

}

Why This Changes Everything

While minor race conditions exist (e.g., a library changing mid-reload), the trade-off is acceptable for development. The benefits are profound:

- Instant Feedback: Tweaking game mechanics, UI, or algorithms happens in real-time.

- State Preservation: Game progress or simulation data persists across reloads.

- Architectural Discipline: Enforces decoupled, state-aware design even in C.

Wellons' Game of Life demo provides a tangible starting point. For developers building engines, simulations, or embedded systems, this technique transforms C from a static compiled language into a dynamic prototyping powerhouse—without sacrificing performance or control.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion