Long before fiber optics and satellites, rural America built its own communication network using the most unlikely of materials: barbed wire fences.

The story of how rural America stayed connected before the telephone companies arrived reads like something out of a steampunk novel. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, farmers and ranchers across the western United States and Canada transformed their barbed wire fences into sprawling communication networks, creating what amounted to a decentralized, cooperative internet of their time.

This forgotten chapter of technological history emerged from a perfect storm of circumstances. The widespread availability of inexpensive barbed wire in the 1890s coincided with the erosion of Alexander Graham Bell's patent monopoly in 1893-1894. This combination suddenly made it possible for independent telephone companies to manufacture equipment that could operate outside the Bell system, while farmers already had miles of wire strung across their properties.

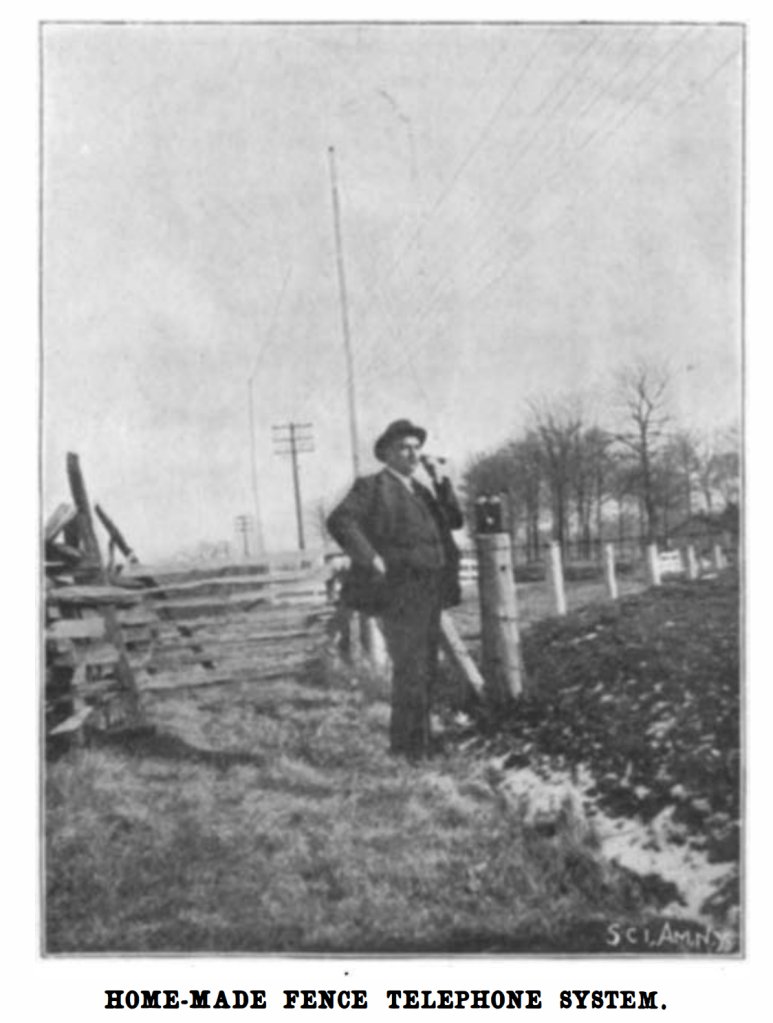

The mechanics were surprisingly simple. Farmers would run smooth copper wire from their homes to nearby barbed wire fences, creating what became known as "fence phones" or "squirrel lines." These weren't just novelty items—they were essential infrastructure for isolated rural communities. The barbed wire networks had no central exchange, no operators, and no monthly bills. Instead, every call made every phone on the system ring, creating a party line where anyone could pick up and listen in.

What made these networks particularly fascinating was their social structure. Unlike the Bell system, which sought to control usage and limit "frivolous telephoning" like courting or gossiping, the fence phone networks embraced free communication. As Bob Holmes notes, "Talk was free, and so people soon began to 'hang out' on the phone." These networks became social hubs where farmers could share weather reports, crop prices, and emergency information across vast distances.

The technical challenges were significant but not insurmountable. Weather frequently caused short circuits, which locals fixed using whatever insulators they could find—leather straps, corn cobs, cow horns, or glass bottles. The quality of the signal traveling over the heavy wire was excellent when conditions permitted, and the DC current from battery-powered telephone handsets could carry voice signals effectively.

These networks weren't limited to small-scale operations. A 1902 report in Telephony magazine described a barbed wire fence telephone network operating between Broomfield and Golden, Colorado, spanning 25 miles and costing only about $10 to build. The system used a "woman operator" to notify workers when to send down water and how much, with a peculiar feature: only the operator could initiate calls, giving her control over the conversation.

The fence phone phenomenon particularly thrived in areas with strong cooperative traditions. During the 1920s, as farmers experienced economic depression years before the Great Depression, these networks became even more vital. In Montana, farmers created the Montana East Line Telephone Association, contributing $25 each plus annual maintenance fees, along with telephone sets, batteries, wire, and insulators.

These networks represented more than just a clever workaround for communication challenges. They embodied principles of decentralization, cooperation, and community ownership that resonate with modern discussions about alternative network architectures. The fence phone networks were ad hoc, non-commercial, and built by the users themselves—characteristics that would feel familiar to anyone involved in today's community mesh networks or decentralized internet projects.

Perhaps most poignantly, these networks existed in a time when the concept of "the internet" was unimaginable, yet they functioned as distributed communication systems that connected people across vast distances without centralized control. They were the original peer-to-peer networks, built not by corporations but by communities who needed to stay connected.

Today, as we grapple with issues of digital divide, network neutrality, and centralized control of communication infrastructure, the story of barbed wire fence phones offers a compelling alternative vision. It reminds us that communication networks don't have to be top-down, commercially driven systems—they can be bottom-up, community-built solutions that serve the needs of their users first and foremost.

The legacy of these networks lives on in unexpected ways. Contemporary artists like Phil Peters and David Rueter have created installations exploring this history, and researchers continue to uncover new details about these forgotten communication systems. Their story challenges our assumptions about technological progress and reminds us that sometimes the most innovative solutions come from the most unlikely materials.

As we look toward the future of communication technology, perhaps we should remember the farmers who turned their fences into phones—proof that when communities need to connect, they'll find a way, even if it means repurposing the tools at hand in ways their original designers never imagined.

from "A CHEAP TELEPHONE SYSTEM FOR FARMERS", Scientific American 82:13 (MARCH 31, 1900), p. 196

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion