GitHub's incident response team discovered that emergency rate-limiting rules, deployed during past abuse incidents, were incorrectly blocking legitimate users during normal browsing. The incident highlights a critical challenge in cloud-scale operations: defensive measures must have lifecycle management just like any other production system.

The Problem: When Emergency Defenses Become Permanent

Platforms like GitHub rely on layered defense mechanisms to maintain availability and responsiveness. Rate limits, traffic controls, and protective measures spread across multiple infrastructure layers all play roles in keeping services healthy during abuse or attacks. However, these same protections can quietly outlive their usefulness and start blocking legitimate users.

This is especially true for protections added as emergency responses during incidents, when responding quickly means accepting broader controls that aren't necessarily meant to be long-term. User feedback recently led GitHub to clean up outdated mitigations, reinforcing that observability is just as critical for defenses as it is for features.

What Users Reported

Users encountered "too many requests" errors during normal, low-volume browsing. Reports appeared on social media from people getting rate-limited when following GitHub links from other services or apps, or just browsing around with no obvious pattern of abuse. These were users making a handful of normal requests hitting rate limits that shouldn't have applied to them.

Users encountered a "Too many requests" error during normal browsing.

Users encountered a "Too many requests" error during normal browsing.

The Investigation: Tracing Through Multiple Layers

Investigating these reports revealed the root cause: protection rules added during past abuse incidents had been left in place. These rules were based on patterns that had been strongly associated with abusive traffic when they were created. The problem is that those same patterns were also matching some logged-out requests from legitimate clients.

These patterns combine industry-standard fingerprinting techniques alongside platform-specific business logic—composite signals that help distinguish legitimate usage from abuse. Unfortunately, composite signals can occasionally produce false positives.

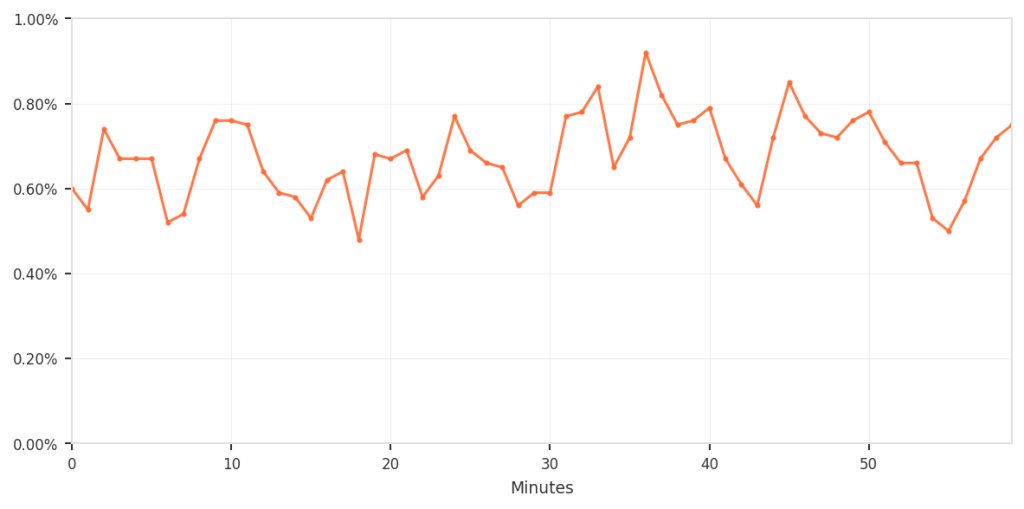

The composite approach did provide filtering. Among requests that matched the suspicious fingerprints, only about 0.5–0.9% were actually blocked; specifically, those that also triggered the business-logic rules. Requests that matched both criteria were blocked 100% of the time.

Not all fingerprint matches resulted in blocks — only those also matching business logic patterns.

Not all fingerprint matches resulted in blocks — only those also matching business logic patterns.

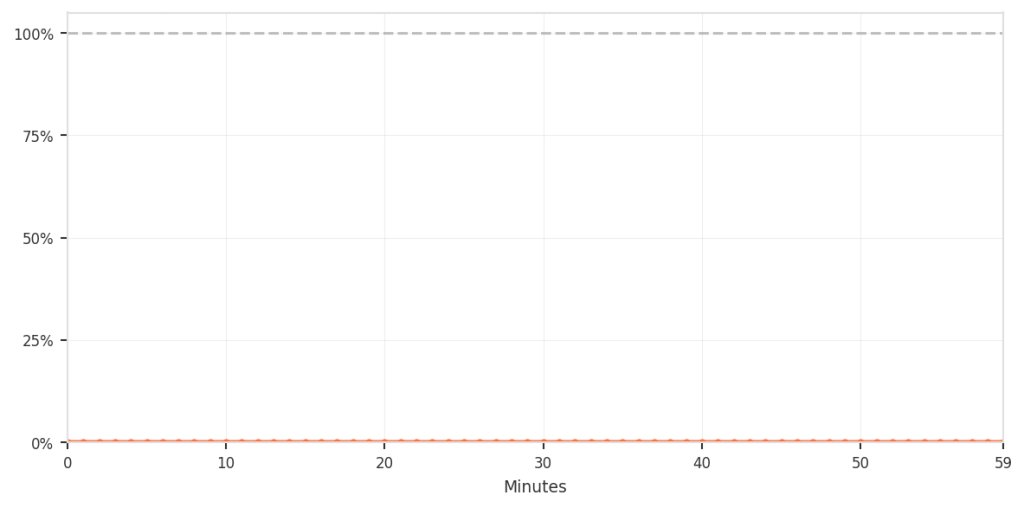

The overall impact was small but consistent. To put this in perspective, false positives represented roughly 0.003-0.04% of total traffic. Although the percentage was low, it still meant that real users were incorrectly blocked during normal browsing, which is not acceptable.

False positives represented roughly 0.003-0.004% of total traffic.

False positives represented roughly 0.003-0.004% of total traffic.

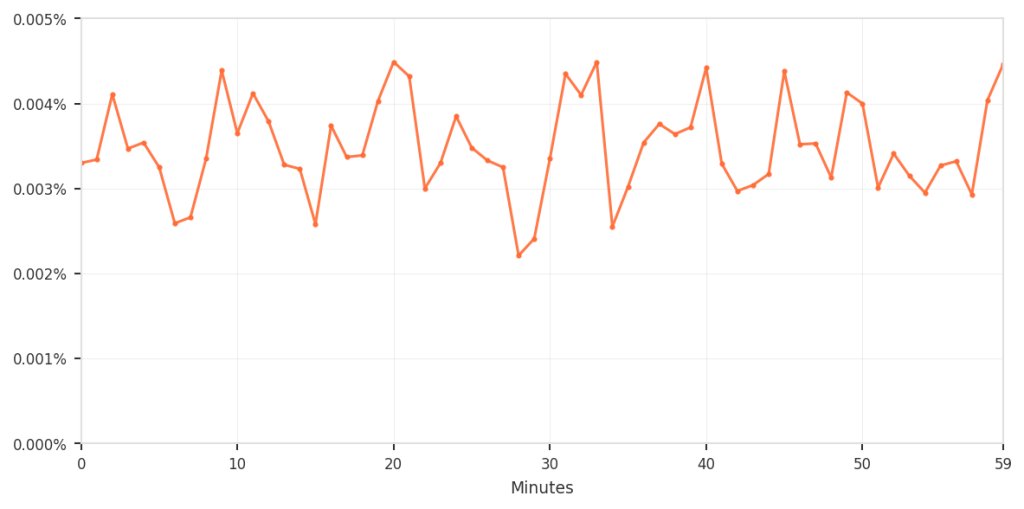

The chart below zooms in specifically on this false-positive pattern over time. In the hour before cleanup, approximately 3-4 requests per 100,000 (0.003-0.004%) were incorrectly blocked.

In the hour before cleanup, approximately 3-4 requests per 100,000 (0.003-0.004%) were incorrectly blocked.

In the hour before cleanup, approximately 3-4 requests per 100,000 (0.003-0.004%) were incorrectly blocked.

Why This Happens at Scale

This is a common challenge when defending platforms at scale. During active incidents, you need to respond quickly, and you accept some tradeoffs to keep the service available. The mitigations are correct and necessary at that moment. Those emergency controls don't age well as threat patterns evolve and legitimate tools and usage change. Without active maintenance, temporary mitigations become permanent, and their side effects compound quietly.

Tracing Through the Stack

The investigation itself highlighted why these issues can persist. When users reported errors, we traced requests across multiple layers of infrastructure to identify where the blocks occurred. To understand why this tracing is necessary, it helps to see how protection mechanisms are applied throughout our infrastructure.

We've built a custom, multi-layered protection infrastructure tailored to GitHub's unique operational requirements and scale, building upon the flexibility and extensibility of open-source projects like HAProxy. Here's a simplified view of how requests flow through these defense layers (simplified to avoid disclosing specific defense mechanisms and to keep the concepts broadly applicable):

Each layer has legitimate reasons to rate-limit or block requests. During an incident, a protection might be added at any of these layers depending on where the abuse is best mitigated and what controls are fastest to deploy.

The challenge: When a request gets blocked, tracing which layer made that decision requires correlating logs across multiple systems, each with different schemas. In this case, we started with user reports and worked backward:

- User reports provided timestamps and approximate behavior patterns

- Edge tier logs showed the requests reaching our infrastructure

- Application tier logs revealed 429 "Too Many Requests" responses

- Protection rule analysis ultimately identified which rules matched these requests

The investigation took us from external reports to distributed logs to rule configurations, demonstrating that maintaining comprehensive visibility into what's actually blocking requests and where is essential.

The Lifecycle of Incident Mitigations

Here's how these protections outlived their purpose:

Each mitigation was necessary when added. But the controls where we didn't consistently apply lifecycle management (setting expiration dates, conducting post-incident rule reviews, or monitoring impact) became technical debt that accumulated until users noticed.

What GitHub Did

The team reviewed these mitigations, analyzing what each one was blocking today versus what it was meant to block when created. They removed the rules that were no longer serving their purpose and kept protections against ongoing threats.

Building Better Lifecycle Management

Beyond the immediate fix, GitHub is improving the lifecycle management of protective controls:

- Better visibility across all protection layers to trace the source of rate limits and blocks

- Treating incident mitigations as temporary by default—making them permanent should require an intentional, documented decision

- Post-incident practices that evaluate emergency controls and evolve them into sustainable, targeted solutions

The Broader Lesson for Cloud Operations

Defense mechanisms—even those deployed quickly during incidents—need the same care as the systems they protect. They need observability, documentation, and active maintenance. When protections are added during incidents and left in place, they become technical debt that quietly accumulates.

This incident underscores a fundamental principle in cloud-scale operations: every component in your infrastructure, whether it's a feature or a defense mechanism, requires lifecycle management. The same discipline applied to feature deprecation and system updates must be applied to security controls and rate-limiting rules.

For organizations running multi-cloud or hybrid cloud strategies, this lesson is particularly relevant. Each cloud provider has its own rate-limiting mechanisms, security controls, and incident response tools. Without proper lifecycle management across all these layers, you risk creating a complex web of overlapping protections that can inadvertently block legitimate traffic while providing diminishing security returns.

The key takeaway: Observability isn't just for features—it's critical for defenses. You can't manage what you can't see, and you can't improve what you don't measure. Regular audits of protection mechanisms, combined with comprehensive logging and tracing capabilities, are essential for maintaining both security and user experience at scale.

Thanks to everyone who reported issues publicly! Your feedback directly led to these improvements. And thanks to the teams across GitHub who worked on the investigation and are building better lifecycle management into how they operate.

Related Resources:

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion