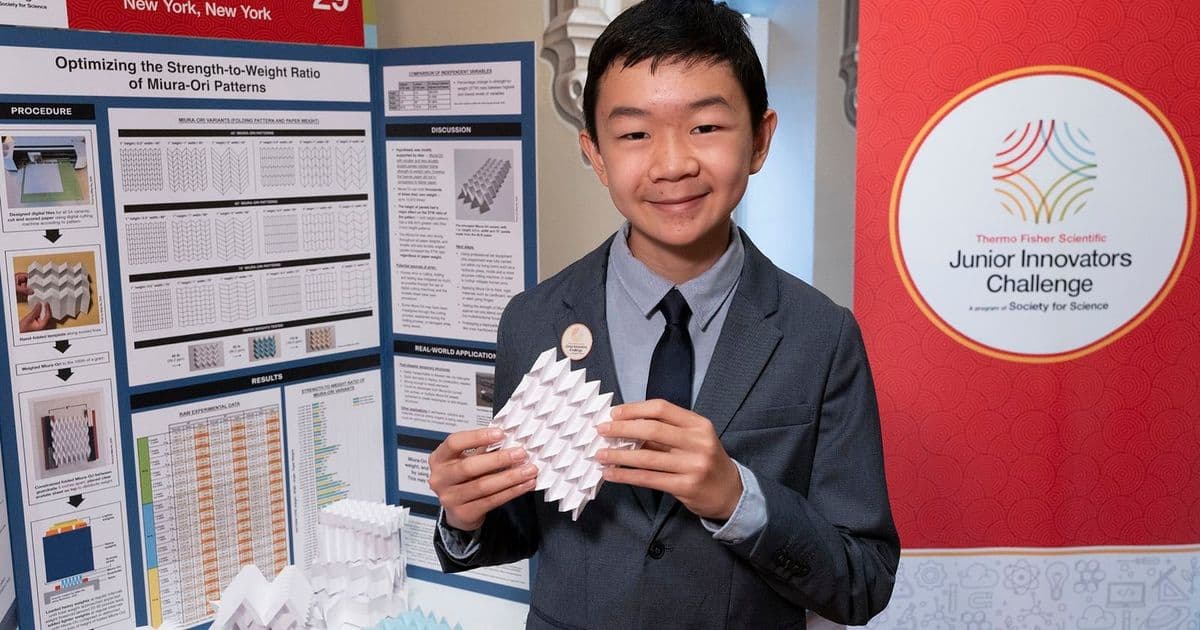

Miles Wu, a 14-year-old from New York City, won a $25,000 science prize for using origami to design emergency shelters that are strong, collapsible, and cost-efficient.

When Hurricane Helene devastated Florida and wildfires raged across Southern California in 2024, 14-year-old Miles Wu saw an opportunity to apply his passion for origami to solve a real-world problem. The ninth-grader from Hunter College High School in New York City had been folding paper for years, but recent disasters made him wonder: could origami patterns create emergency shelters that are both strong and easy to deploy?

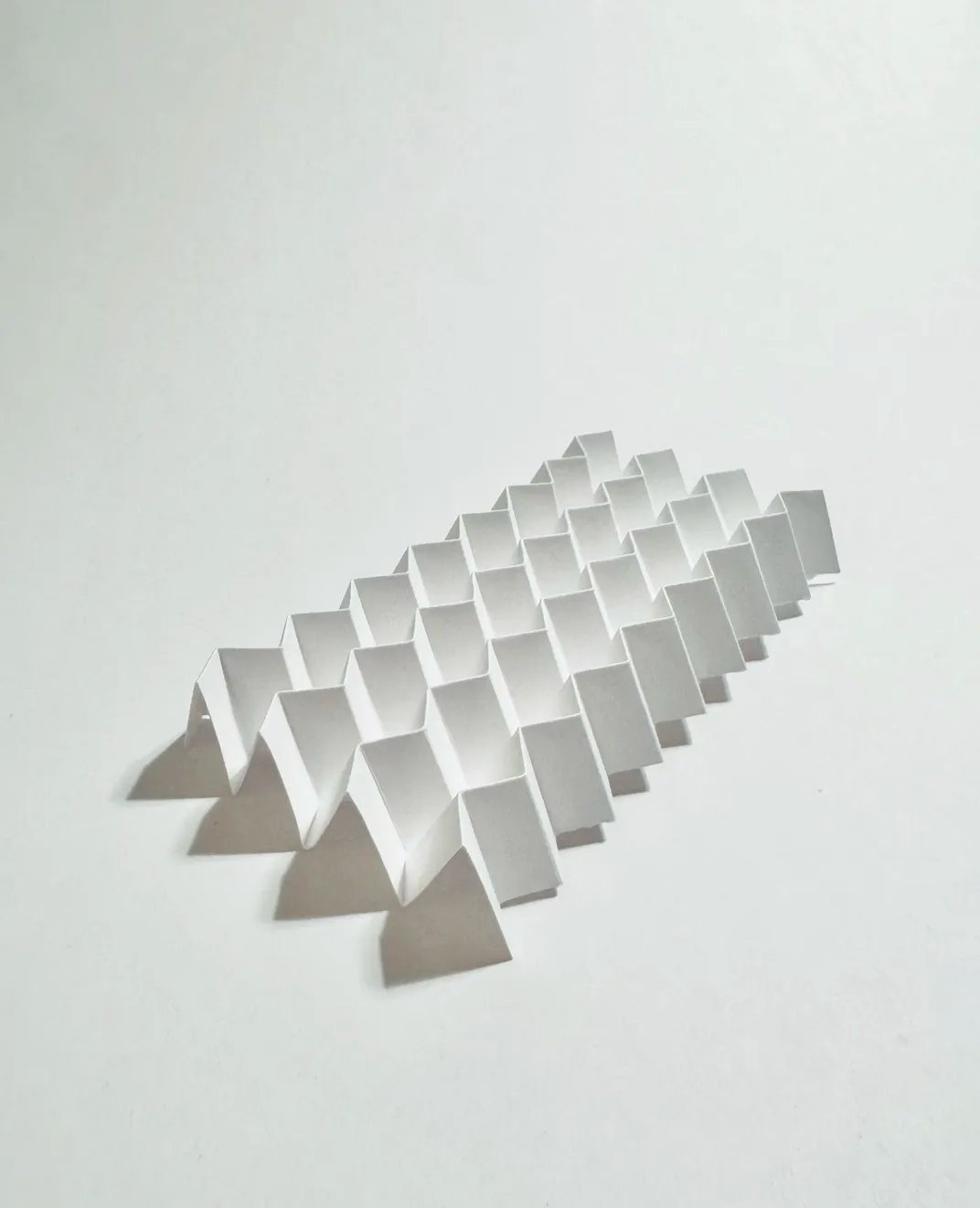

Wu's journey began with a simple piece of paper folded into a Miura-ori pattern—a series of tessellating parallelograms that can fold or unfold in one smooth motion. Named after Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura, who pioneered its use in spacecraft design, this fold can compress large sheets into compact forms while maintaining remarkable strength. When Wu discovered that his folded paper could hold 10,000 times its own weight, he knew he was onto something.

To test his hypothesis, Wu transformed his family's living room into a makeshift laboratory. He designed 54 different variants of the Miura-ori pattern using computer software, adjusting variables like height, width, and parallelogram angles. Using three types of paper—copy paper, light cardstock, and heavy cardstock—he created 108 different folded samples.

Initially, Wu assumed the strongest pattern might hold around 50 pounds. He started testing with textbooks and household items, but quickly realized he needed more weight. "I finally had to ask my parents to buy 50-pound exercise weights," he recalls. The strongest pattern he tested held over 200 pounds—10,000 times its own weight. "To put it in other words, this ratio is the equivalent of a New York City taxicab supporting the weight of over 4,000 elephants!" Wu exclaims.

Wu's innovation earned him the top prize of $25,000 at the 2025 Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge, the nation's leading STEM competition for middle school students. Among 30 finalists who traveled to Washington, D.C. for team challenges, Wu stood out not just for his research but for his ability to apply origami principles to build components of a movable crab arm, demonstrating innovation and collaboration under pressure.

Maya Ajmera, president and CEO of Society for Science, praised Wu's project for transforming a lifelong passion into rigorous engineering research. "He was somebody who transformed a lifelong passion for origami into a really rigorous structural engineering project, where he was testing dozens of fold designs to measure their strength and potential," she says.

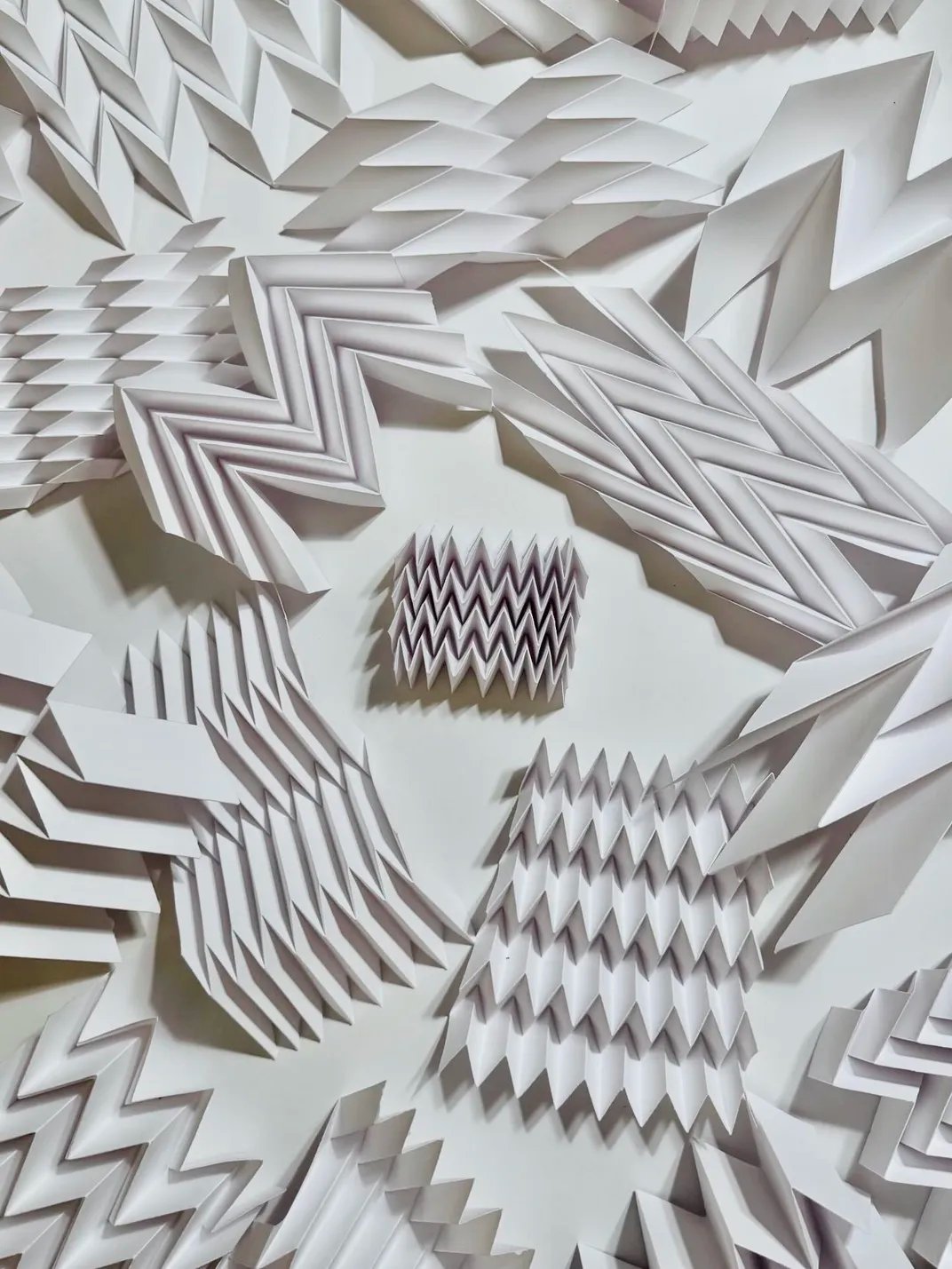

The potential applications extend far beyond emergency shelters. Origami techniques are already used in biomedical devices like stents and catheters, self-assembling robots, and spacecraft solar panels. Recently, a Brigham Young University student discovered a new family of origami patterns called "bloom patterns" that resemble flowers as they unfold and could be used to build telescopes and satellites.

However, scaling Wu's research from paper models to full-scale disaster shelters presents significant engineering challenges. Glaucio H. Paulino, an engineer at Princeton University who studies origami applications, notes that origami properties don't scale linearly. "Actual shelters need to respond to multidirectional loads and durability demands that may require arches and systems level integration beyond small-scale compression tests," he explains.

Wu acknowledges these challenges but remains undeterred. His next steps include developing an actual prototype of an emergency shelter using either a singular Miura-ori curved into an arch or multiple sheets combined to create a tent-like structure. He plans to test the patterns against multidirectional forces, not just lateral compression, and explore other origami patterns for different scenarios.

"I definitely want to continue exploring and researching origami and how it intersects with STEM," Wu says. His work demonstrates how ancient art forms can find new life in modern engineering challenges, potentially saving lives when disasters strike. As climate change increases the frequency and severity of natural disasters, innovations like Wu's could become increasingly vital for rapid, effective emergency response.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion