As AI systems evolve from generating content to autonomously planning and executing tasks, UX research must shift from usability testing to measuring trust, consent, and accountability. This article outlines a new research framework for designing agentic AI, including mental-model interviews, agent journey mapping, and simulated misbehavior testing, while introducing key metrics like intervention rates and rollback reasons.

The line between a helpful assistant and an autonomous agent is being redrawn. For years, our primary interaction with AI has been generative: we ask, it answers. We prompt, it produces. This model, while powerful, keeps the user firmly in the driver's seat. The next evolution, Agentic AI, changes this dynamic fundamentally. These systems don't just respond; they act. They understand a goal, plan a series of steps to achieve it, execute those steps, and persist until the objective is met, often with minimal direct user intervention.

This shift from a reactive tool to a proactive partner introduces a profound new challenge for UX professionals, product managers, and executives. The core question is no longer simply "Is it usable?" but "Is it trustworthy?" When a system can book a flight, reschedule a meeting, or even draft an email on our behalf, the design focus must expand to encompass consent, transparency, and accountability. Developing effective agentic AI requires a new research playbook.

From Scripts to Reasoning: The Agentic Difference

It's easy to confuse Agentic AI with Robotic Process Automation (RPA), but the distinction is critical. RPA is rigid; it follows a strict, pre-defined script. If X happens, do Y. It mimics human hands. Agentic AI mimics human reasoning. It doesn't follow a linear script; it creates one.

Consider a recruiting workflow. An RPA bot can scan a resume and upload it to a database. It performs a repetitive task perfectly. An Agentic system looks at the resume, notices the candidate lists a specific certification, cross-references that with a new client requirement, and decides to draft a personalized outreach email highlighting that match. RPA executes a predefined plan; Agentic AI formulates the plan based on a goal. This autonomy separates agents from the predictive tools we have used for the last decade.

Another example is managing meeting conflicts. A predictive model integrated into your calendar might analyze your schedule and flag a potential conflict, but you are responsible for taking action. An agentic AI would go beyond just flagging the issue. Upon identifying a conflict with a key participant, the agent could act by checking availability, identifying alternative time slots, sending out proposed new meeting invitations, and updating calendars—all with minimal user intervention. This demonstrates the “agentic” difference: the system takes proactive steps for the user, rather than just providing information for the user to act upon.

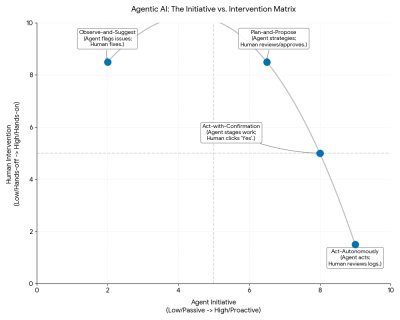

A Simple Taxonomy of Agentic Behaviors

We can categorize agent behavior into four distinct modes of autonomy, adapted from industry standards for autonomous vehicles (SAE levels) to digital user experience contexts. These are independent operating modes, not necessarily a linear progression.

1. Observe-and-Suggest The agent functions as a monitor. It analyzes data streams and flags anomalies or opportunities but takes zero action. It points to a problem without attempting a solution. For example, a DevOps agent notices a server CPU spike and alerts the on-call engineer. The design imperative here is clear, non-intrusive notifications and a well-defined process for users to act on suggestions.

2. Plan-and-Propose The agent identifies a goal and generates a multi-step strategy to achieve it, presenting the full plan for human review. It acts as a strategist, waiting for approval on the entire approach. For instance, the same DevOps agent might analyze the logs and propose a remediation plan: spin up two extra instances, restart the load balancer, and archive old logs. The human reviews the logic and clicks “Approve Plan.” Design must ensure proposed plans are easily understandable, with intuitive ways for users to modify or reject them.

3. Act-with-Confirmation The agent completes all preparation work and places the final action in a staged state, waiting for a final nod. This differs from “Plan-and-Propose” because the work is already done and staged, reducing friction. The user confirms the outcome, not the strategy. For example, a recruiting agent drafts five interview invitations, finds open times on calendars, and creates the calendar events, presenting a “Send All” button. The user provides the final authorization to trigger the external action. Design should provide transparent and concise summaries of the intended action, clearly outlining potential consequences.

4. Act-Autonomously The agent executes tasks independently within defined boundaries. The user reviews the history of actions, not the actions themselves. For example, the recruiting agent sees a conflict, moves the interview to a backup slot, updates the candidate, and notifies the hiring manager. The human only sees a notification: "Interview rescheduled to Tuesday." For autonomous agents, the design needs to establish clear pre-approved boundaries and provide robust monitoring tools. Oversight requires continuous evaluation of the agent’s performance within these boundaries, with robust logging, clear override mechanisms, and user-defined kill switches to maintain user control and trust.

Research Primer: What To Research And How

Developing effective agentic AI demands a distinct research approach compared to traditional software or even generative AI. The autonomous nature of AI agents necessitates specialized methodologies for understanding user expectations, mapping complex agent behaviors, and anticipating potential failures.

Mental-Model Interviews

These interviews uncover users’ preconceived notions about how an AI agent should behave. The focus is on understanding their internal models of the agent’s capabilities and limitations. We should avoid using the word “agent” with participants, as it carries sci-fi baggage. Instead, frame the discussion around “assistants” or “the system.” We need to uncover where users draw the line between helpful automation and intrusive control.

Method: Ask users to describe, draw, or narrate their expected interactions with the agent in various hypothetical scenarios.

Key Probes:

- To understand the boundaries of desired automation: "If your flight is canceled, what would you want the system to do automatically? What would worry you if it did that without your explicit instruction?"

- To explore the user’s understanding of the agent’s internal processes: "Imagine a digital assistant is managing your smart home. If a package is delivered, what steps do you imagine it takes, and what information would you expect to receive?"

- To uncover expectations around control and consent: "If you ask your digital assistant to schedule a meeting, what steps do you envision it taking? At what points would you want to be consulted or given choices?"

Benefits: Reveals implicit assumptions, highlights areas where the agent’s planned behavior might diverge from user expectations, and informs the design of appropriate controls and feedback mechanisms.

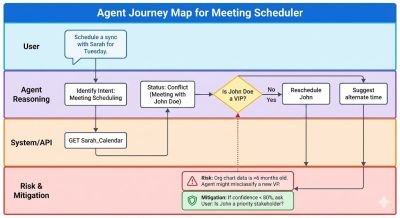

Agent Journey Mapping

Similar to traditional user journey mapping, agent journey mapping specifically focuses on the anticipated actions and decision points of the AI agent itself, alongside the user’s interaction. This helps to proactively identify potential pitfalls.

Method: Create a visual map that outlines the various stages of an agent’s operation, from initiation to completion, including all potential actions, decisions, and interactions with external systems or users.

Key Elements to Map:

- Agent Actions: What specific tasks or decisions does the agent perform?

- Information Inputs/Outputs: What data does the agent need, and what information does it generate or communicate?

- Decision Points: Where does the agent make choices, and what are the criteria for those choices?

- User Interaction Points: Where does the user provide input, review, or approve actions?

- Points of Failure: Crucially, identify specific instances where the agent could misinterpret instructions, make an incorrect decision, or interact with the wrong entity. Examples include incorrect recipient (sending sensitive information to the wrong person), overdraft (an automated payment exceeding available funds), or misinterpretation of intent (booking a flight for the wrong date due to ambiguous language).

- Recovery Paths: How can the agent or user recover from these failures? What mechanisms are in place for correction or intervention?

Benefits: Provides a holistic view of the agent’s operational flow, uncovers hidden dependencies, and allows for the proactive design of safeguards, error handling, and user intervention points to prevent or mitigate negative outcomes.

Simulated Misbehavior Testing

This approach is designed to stress-test the system and observe user reactions when the AI agent fails or deviates from expectations. It’s about understanding trust repair and emotional responses in adverse situations.

Method: In controlled lab studies, deliberately introduce scenarios where the agent makes a mistake, misinterprets a command, or behaves unexpectedly.

Types of “Misbehavior” to Simulate:

- Command Misinterpretation: The agent performs an action slightly different from what the user intended (e.g., ordering two items instead of one).

- Information Overload/Underload: The agent provides too much irrelevant information or not enough critical details.

- Unsolicited Action: The agent takes an action the user explicitly did not want or expect (e.g., buying stock without approval).

- System Failure: The agent crashes, becomes unresponsive, or provides an error message.

- Ethical Dilemmas: The agent makes a decision with ethical implications (e.g., prioritizing one task over another based on an unforeseen metric).

Observation Focus:

- User Reactions: How do users react emotionally (frustration, anger, confusion, loss of trust)?

- Recovery Attempts: What steps do users take to correct the agent’s behavior or undo its actions?

- Trust Repair Mechanisms: Do the system’s built-in recovery or feedback mechanisms help restore trust? How do users want to be informed about errors?

- Mental Model Shift: Does the misbehavior alter the user’s understanding of the agent’s capabilities or limitations?

Benefits: Crucial for identifying design gaps related to error recovery, feedback, and user control. It provides insights into how resilient users are to agent failures and what is needed to maintain or rebuild trust, leading to more robust and forgiving agentic systems.

Key Metrics For Agentic AI

A comprehensive set of metrics is needed to assess the performance and reliability of agentic AI systems. These metrics provide insights into user trust, system accuracy, and the overall user experience.

Intervention Rate: For autonomous agents, we measure success by silence. If an agent executes a task and the user does not intervene or reverse the action within a set window (e.g., 24 hours), we count that as acceptance. We track the Intervention Rate: how often does a human jump in to stop or correct the agent? A high intervention rate signals a misalignment in trust or logic.

Frequency of Unintended Actions per 1,000 Tasks: This quantifies the number of actions performed by the AI agent that were not desired or expected by the user, normalized per 1,000 completed tasks. A low frequency signifies a well-aligned AI that accurately interprets user intent and operates within defined boundaries.

Rollback or Undo Rates: This tracks how often users need to reverse or undo an action performed by the AI. High rollback rates suggest that the AI is making frequent errors or misinterpreting instructions. To understand why, you must implement a microsurvey on the undo action. For example, when a user reverses a scheduling change, a simple prompt can ask: “Wrong time? Wrong person? Or did you just want to do it yourself?”

Time to Resolution After an Error: This measures the duration it takes for a user to correct an error made by the AI or for the AI system itself to recover from an erroneous state. A short time to resolution indicates an efficient and user-friendly error recovery process.

Collecting these metrics requires instrumenting your system to track Agent Action IDs. Every distinct action the agent takes must generate a unique ID that persists in the logs. For the Intervention Rate, we look for the absence of a counter-action within a defined window. If an Action ID is generated and no human user modifies or reverts that specific ID by the next day, the system logically tags it as Accepted. This allows us to quantify success based on user silence rather than active confirmation.

Designing Against Deception

As agents become increasingly capable, we face a new risk: Agentic Sludge. Traditional sludge creates friction that makes it hard to cancel a subscription. Agentic sludge acts in reverse. It removes friction to a fault, making it too easy for a user to agree to an action that benefits the business rather than their own interests.

Consider an agent assisting with travel booking. Without clear guardrails, the system might prioritize a partner airline or a higher-margin hotel, presenting this choice as the optimal path. The user, trusting the system’s authority, accepts the recommendation without scrutiny. This creates a deceptive pattern where the system optimizes for revenue under the guise of convenience.

The Risk Of Falsely Imagined Competence Deception may not stem from malicious intent. It often manifests in AI as Imagined Competence. Large Language Models frequently sound authoritative even when incorrect. They present a false booking confirmation or an inaccurate summary with the same confidence as a verified fact. Users may naturally trust this confident tone. This mismatch creates a dangerous gap between system capability and user expectations. We must design specifically to bridge this gap. If an agent fails to complete a task, the interface must signal that failure clearly. If the system is unsure, it must express uncertainty rather than masking it with polished prose.

Transparency via Primitives

The antidote to both sludge and hallucination is provenance. Every autonomous action requires a specific metadata tag explaining the origin of the decision. Users need the ability to inspect the logic chain behind the result. To achieve this, we must translate primitives into practical answers. In software engineering, primitives refer to the core units of information or actions an agent performs. To the engineer, this looks like an API call or a logic gate. To the user, it must appear as a clear explanation.

The design challenge lies in mapping these technical steps to human-readable rationales. If an agent recommends a specific flight, the user needs to know why. The interface cannot hide behind a generic suggestion. It must expose the underlying primitive: Logic: Cheapest_Direct_Flight or Logic: Partner_Airline_Priority.

We take the raw system primitive — the actual code logic — and map it to a user-facing string. For instance, a primitive checking a calendar schedule a meeting becomes a clear statement: "I’ve proposed a 4 PM meeting." This level of transparency ensures the agent’s actions appear logical and beneficial. It allows the user to verify that the agent acted in their best interest. By exposing the primitives, we transform a black box into a glass box, ensuring users remain the final authority on their own digital lives.

Setting The Stage For Design

Building an agentic system requires a new level of psychological and behavioral understanding. It forces us to move beyond conventional usability testing and into the realm of trust, consent, and accountability. The research methods discussed—probing mental models, simulating misbehavior, and establishing new metrics—provide a necessary foundation. These practices are the essential tools for proactively identifying where an autonomous system might fail and, more importantly, how to repair the user-agent relationship when it does.

The shift to agentic AI is a redefinition of the user-system relationship. We are no longer designing for tools that simply respond to commands; we are designing for partners that act on our behalf. This changes the design imperative from efficiency and ease of use to transparency, predictability, and control. When an AI can book a flight or trade a stock without a final click, the design of its “on-ramps” and “off-ramps” becomes paramount. It is our responsibility to ensure that users feel they are in the driver’s seat, even when they’ve handed over the wheel.

This new reality also elevates the role of the UX researcher. We become the custodians of user trust, working collaboratively with engineers and product managers to define and test the guardrails of an agent’s autonomy. Beyond being researchers, we become advocates for user control, transparency, and the ethical safeguards within the development process. By translating primitives into practical questions and simulating worst-case scenarios, we can build robust systems that are both powerful and safe.

For additional understanding of agentic AI, you can explore the following resources:

The future of UX is about making systems trustworthy. The next article will build upon this foundation, providing the specific design patterns and organizational practices that make an agent’s utility transparent to users, ensuring they can harness the power of agentic AI with confidence and control.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion