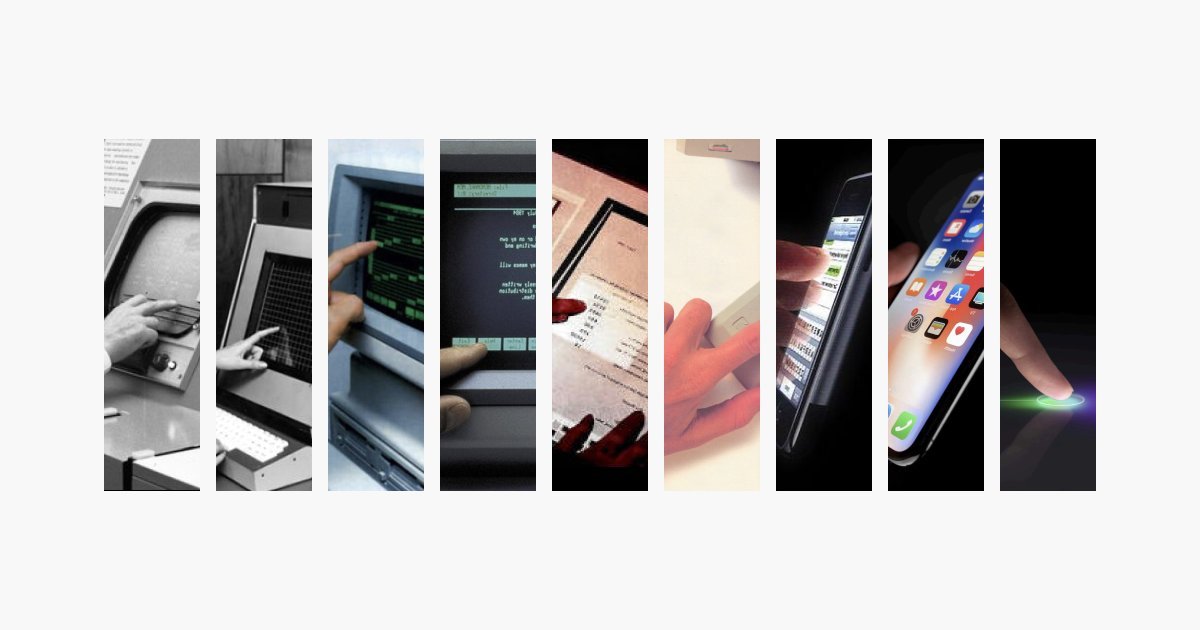

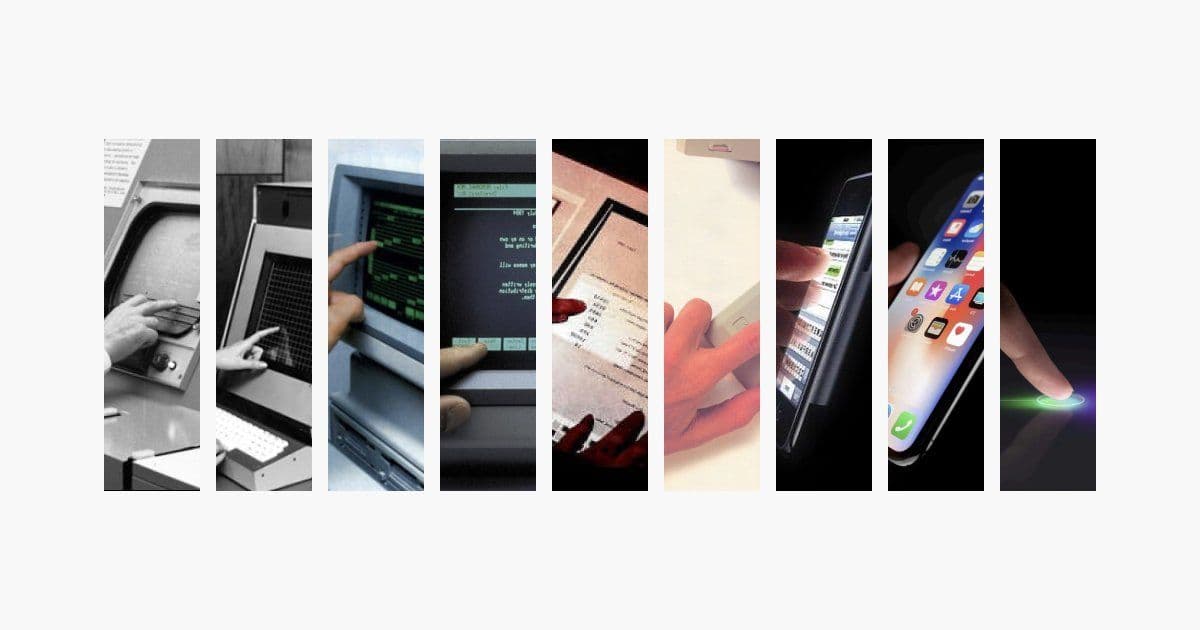

An in‑depth exploration of the subtle design principles that turn a touch screen into a natural extension of human intent. From metaphoric gestures to kinetic physics, the article dissects why certain interactions feel effortless and how developers can embed these insights into their next product.

The Invisible Engine Behind Every Tap

When designers talk about interaction design, the word often feels like a buzzword that hides a handful of vague principles: "make it intuitive," "focus on user flow," or "apply best practices." In practice, the discipline is a mix of art, psychology, and low‑level physics that informs how a finger, a stylus, or a voice command is translated into a fluid, predictable experience.

“Interaction design is an artform to make experiences that fluidly respond to human intent.” – Rauno

The essay by Rauno (2023) dives into the invisible details that make interactions feel natural. The following sections distill the key take‑aways, illustrate them with concrete examples, and show how developers can harness these concepts to build products that feel like extensions of themselves.

1. Metaphors: The Bridge Between the Physical and the Digital

A swipe, a pinch, a tap—these gestures are not arbitrary. They map onto real‑world actions:

- Swiping mirrors turning a page or sliding a deck of cards. The direction of the gesture (horizontal for paging, vertical for scrolling) aligns with how we organize information in physical space.

- Pinching is akin to zooming in on a map with a magnifying glass or adjusting a camera lens. The two‑finger anchor point mimics the way we hold objects with precision.

When a gesture feels like a natural extension of a real‑world action, the interface requires no cognitive load. Developers can reinforce this by:

- Consistent gesture mapping – avoid reassigning familiar gestures to unrelated actions.

- Visual affordances – subtle shadows, motion cues, or iconography that hint at the underlying metaphor.

Implication: A consistent metaphor reduces onboarding time and improves user retention, especially in complex applications.

2. Kinetic Physics: Momentum, Friction, and the “Feel” of Motion

The Dynamic Island on iOS is a prime example of kinetic physics in action. When a user swipes up to unlock the phone, the overlay behaves like a lightweight card sliding off a table: it retains momentum, slightly bounces, and settles into a new state.

“Notice how the gesture retains the momentum and angle at which it was thrown.”

Implementing realistic physics involves:

- Spring curves – a configurable stiffness and damping factor that controls acceleration and settling.

- Thresholds – a minimum distance or velocity that must be met before an action commits.

Implication: Proper physics make interactions feel responsive and prevent accidental triggers, which is critical for destructive actions like deleting data.

3. Responsive Gestures: Triggering on Intent, Not Just Completion

Not all gestures should wait until the finger lifts. Lightweight actions (e.g., opening a search overlay) can trigger mid‑gesture, while destructive actions (e.g., closing an app) should wait until the gesture ends.

“Waiting for the gesture to end before unlocking would make the interface feel broken and provide less affordance.”

Developers can adopt a hybrid approach:

- Intent detection – analyze velocity and distance to decide whether to commit.

- Feedback loops – provide immediate visual or haptic feedback to confirm the action.

Implication: This strategy balances speed and safety, a trade‑off that is especially relevant in mobile contexts.

4. Spatial Consistency: Where Things Come From

The Dynamic Island’s behavior when launching Spotify versus the native Clock app illustrates spatial consistency. Launching an app from an icon preserves the origin point, while the Clock’s timer is a dedicated module that always expands from the island.

“The app slides in from the right, it communicates where it is spatially.”

By maintaining spatial consistency:

- Users can infer relationships between UI elements.

- It reduces the cognitive load of locating newly opened content.

Implication: Consistent spatial cues are essential for complex workflows where multiple panels or windows coexist.

5. Frequency & Novelty: When Motion Becomes a Burden

Animations should delight, not fatigue. Repeatedly animating a command menu that appears hundreds of times a day can become a cognitive nuisance.

“When an interaction is used frequently, the novelty is diminished.”

Best practices:

- Selective animation – animate only when the action is unexpected or when it adds value.

- Speed tuning – keep animations snappy; avoid long delays that feel sluggish.

Implication: Thoughtful animation design improves perceived performance and keeps users engaged.

6. Fidgetability: Design for Human Habits

Fidgeting—repetitive, low‑effort motions—can be harnessed to create satisfying interactions. Think of the AirPods case or the Apple Pencil’s twistable tip.

“Fidgetability could also be an after‑thought, or a happy side‑effect.”

By embedding small, repeatable interactions:

- Users can engage without conscious effort.

- It can serve as a subtle form of feedback or status indication.

Implication: Fidgetable elements can improve user satisfaction, especially in high‑stress or repetitive tasks.

7. Scroll Landmarks & Touch Visibility: Keeping Context

On macOS, shaking the mouse reveals the pointer; on mobile, double‑tapping a scrollbar can set a landmark. These interactions help users maintain context when navigating large content.

“The interface renders a temporary representation of what's underneath the finger.”

Implementation tips:

- Dynamic overlays – show magnified content or a preview when the finger covers an element.

- Contextual landmarks – allow users to bookmark positions for quick return.

Implication: These small conveniences reduce frustration and improve navigation efficiency.

8. Implicit Input: Letting Context Do the Work

Modern interfaces can infer intent from context—Apple Maps showing a route without unlocking, or Spotify adjusting controls while driving. This is the pinnacle of implicit input.

“The interface makes use of context as input and can infer what you're trying to do without asking.”

To leverage implicit input:

- Context sensors – use GPS, accelerometer, or time of day.

- Adaptive UI – adjust layout or controls based on the inferred state.

Implication: Implicit input reduces friction, especially in multimodal or hands‑free scenarios.

9. Fitts’s Law & the Magic of Corners

Fitts’s Law states that the time to reach a target depends on its size and distance. Operating systems exploit this by placing frequently used actions in corners or by using radial menus that appear around the pointer.

“The target size is infinite because the pointer can't overshoot past the corner.”

Design takeaway:

- Place critical actions in corners or near the pointer’s natural path.

- Use radial menus to provide uniform distance and size for all options.

Implication: Proper placement reduces selection time and increases overall productivity.

10. Scrolling & Direct Manipulation: The Magic Mouse Effect

The Magic Mouse’s ability to scroll in the background of a focused window, while other windows ignore the gesture, demonstrates how hardware can influence interaction design.

“Scrolling is cancelled explicitly by focusing another window.”

Developers can emulate this by:

- Pointer‑centric scrolling – only the element under the pointer receives scroll events.

- Focus management – ensure that other UI elements do not inadvertently capture gestures.

Implication: This leads to a more predictable and satisfying scrolling experience.

Closing the Loop

The journey from a finger tap to a fully realized interaction is paved with subtle design choices—metaphors, physics, spatial logic, and implicit cues. Each decision, though small, compounds to create an interface that feels like an extension of the user’s own body and mind.

For developers and designers, the takeaway is clear: invest time in understanding the underlying principles that make interactions feel natural. By grounding design decisions in these concepts, you can build products that not only look good but also feel inevitable.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion