In 1976, a 20-year-old Bill Gates penned an open letter to hobbyists, decrying software piracy and questioning why hardware buyers wouldn't pay for the software that made their expensive machines useful.

In February 1976, a 20-year-old Bill Gates typed an open letter that would become one of the most famous documents in software history. Addressed to the burgeoning hobbyist community, the letter titled "An Open Letter to Hobbyists" laid bare a frustration that would echo through the decades of digital distribution: software piracy.

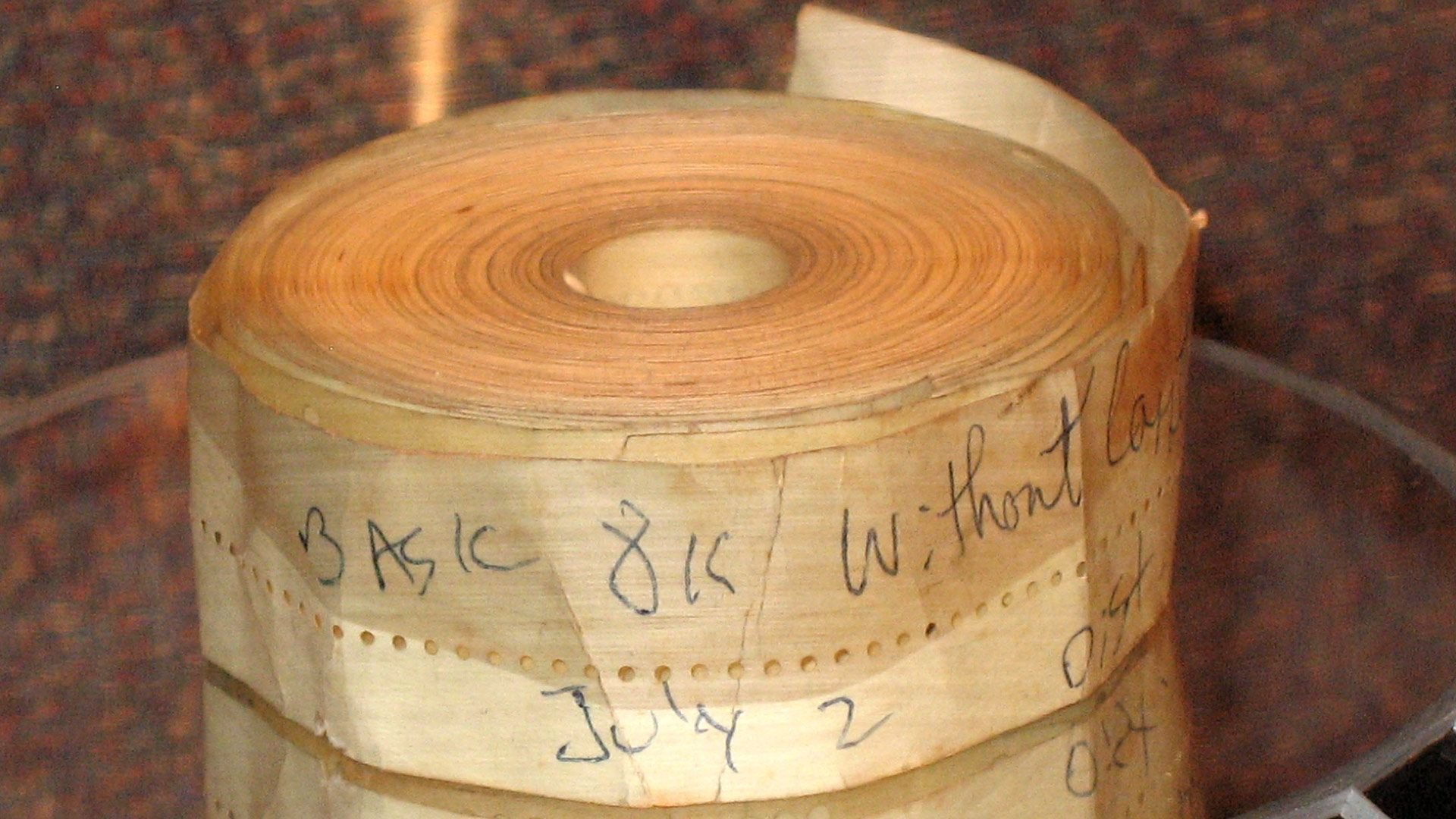

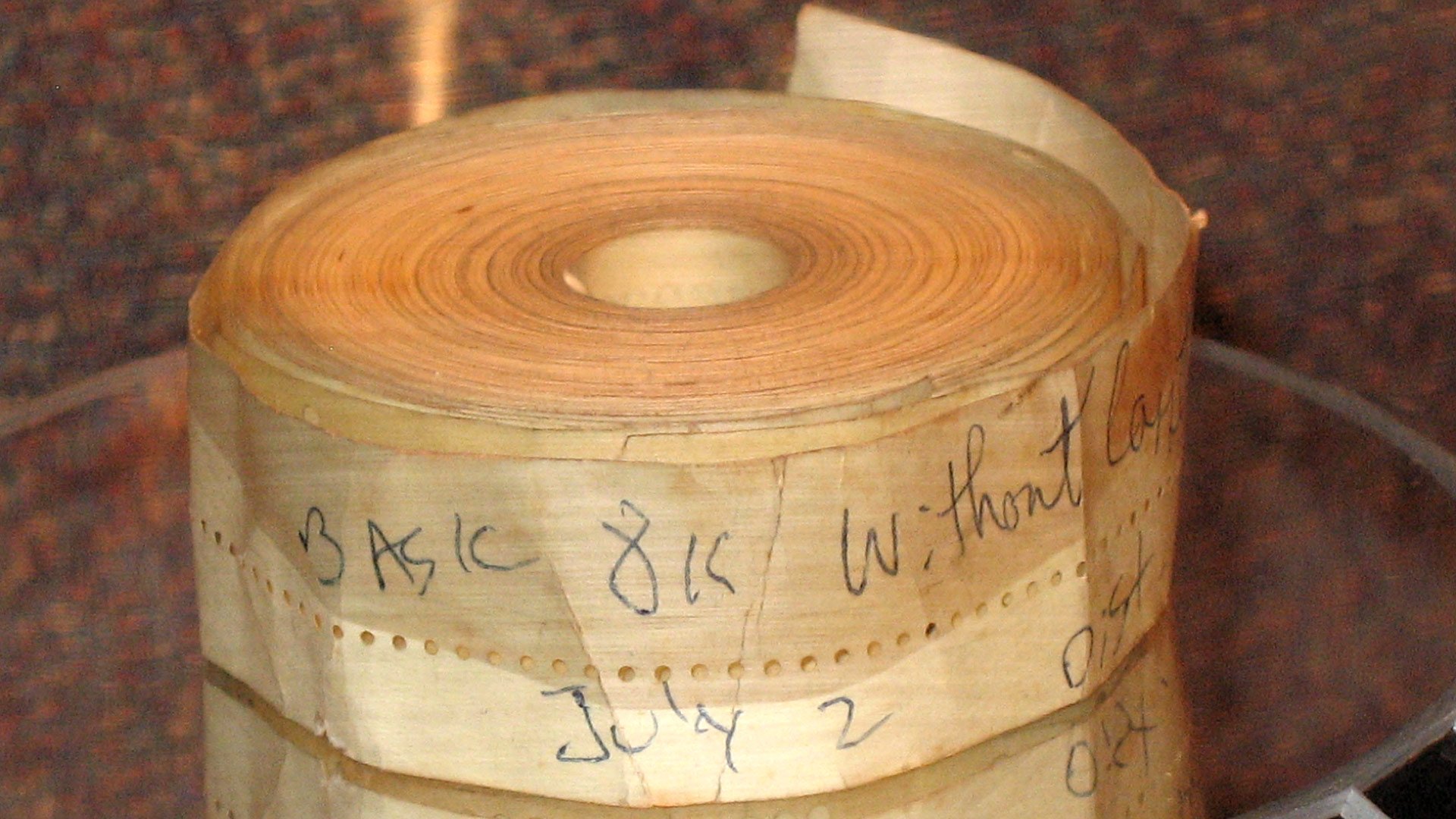

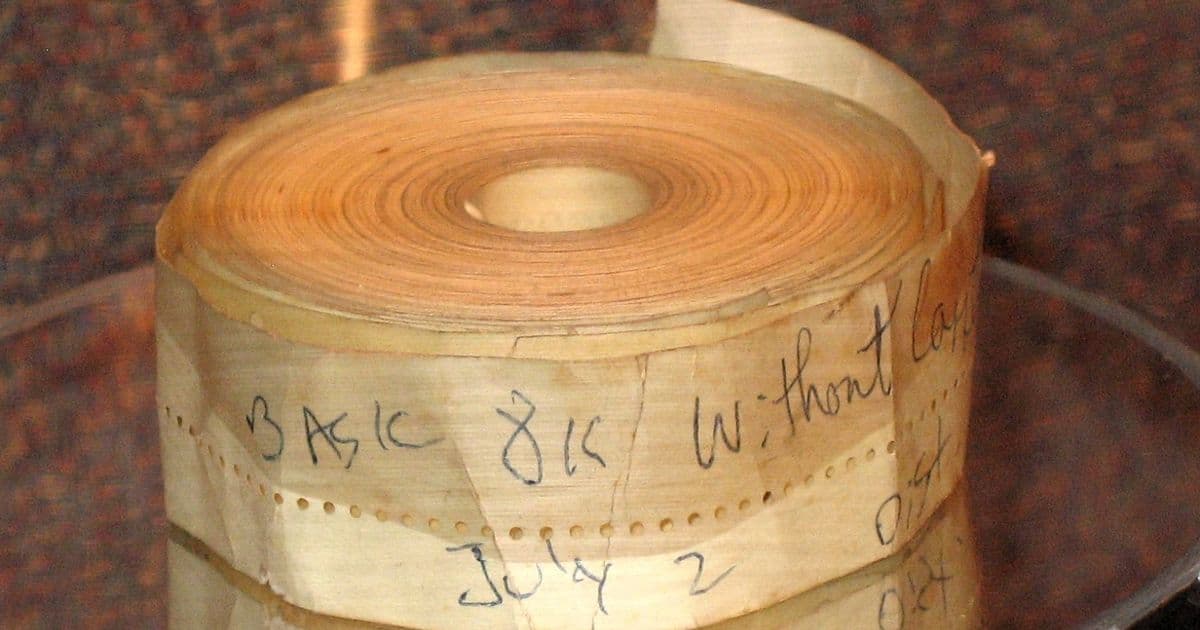

This is an original copy of 8K BASIC on paper tape for the MITS Altair 8800 computer. The BASIC interpreter was written by Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Monte Davidoff. The tape is labeled "BASIC 8K without cassette" and dated July 2 (1975).

(Image credit: Swtpc6800 Michael Holley)

The context was the Altair 8800, a machine that ignited the personal computer revolution in 1975. With its Intel 8080 CPU and S-100 bus cards, the Altair represented the first truly accessible computer for enthusiasts. However, in its default configuration, it lacked even basic input and output devices—no keyboard, no screen, just a front panel of switches and lights.

Gates and Paul Allen saw an opportunity. They developed Altair BASIC, a BASIC interpreter that would transform the Altair from a hobbyist curiosity into a functional computer. It was Micro-Soft's (as the company was then known) first commercial product, representing months of development work.

The problem, as Gates saw it, was that while hundreds of people were using Altair BASIC, very few had actually paid for it. The situation had been exacerbated by the Homebrew Computer Club, where members had created copies of the software using high-speed tape punches—producing up to 50 copies at a time. Some hobbyists even bundled the pirated software with their hardware projects, essentially giving away the fruits of Gates and Allen's labor.

"As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software," Gates wrote, his frustration evident. "Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?"

The economics were stark. Developing software required significant investment: computer time at expensive mainframe facilities, manual writing, media duplication, and distribution. Gates calculated that Micro-Soft was operating as "a break-even operation" at best. The lack of revenue meant that instead of hiring more programmers to create better software, the company remained a small operation struggling to survive.

Gates' argument was pragmatic as much as ethical. If the hobbyist community wanted better software—more sophisticated applications, better tools, more innovation—then developers needed to be compensated for their work. "Nothing would please me more than being able to hire ten programmers and deluge the hobby market with good software," he wrote.

This is an original copy of 8K BASIC on paper tape for the MITS Altair 8800 computer. The BASIC interpreter was written by Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Monte Davidoff. The tape is labeled "BASIC 8K without cassette" and dated July 2 (1975).

The letter's timing was significant. In 1976, the personal computer industry was still in its infancy. The concept of commercial software was novel—many early computer enthusiasts came from academic or research backgrounds where software was freely shared. The idea that code could be proprietary, that developers could and should be paid for their work, was still being established.

Fifty years later, Gates' letter reads as remarkably prescient. The tension between free sharing and commercial development that he identified would define the software industry for decades. Open source software, shareware, subscription models, app stores, digital rights management—all of these developments can trace their roots to the fundamental question Gates posed: who should pay for software, and how?

The irony is not lost on historians. The company Gates co-founded would go on to become one of the most profitable software businesses in history, built largely on the principle that software has value and should be purchased. Yet the open letter also foreshadowed the collaborative, sharing ethos that would eventually give rise to the open source movement.

What makes the letter particularly fascinating is its window into the birth of an industry. Gates wasn't just complaining about lost revenue; he was helping to define the rules of a new economic ecosystem. The personal computer revolution wasn't just about hardware—it was about creating a sustainable model for software development that could support innovation and growth.

The debate Gates initiated continues today, albeit in evolved forms. Digital distribution has made copying easier than ever, while subscription models and cloud services have created new revenue streams. Yet the fundamental tension remains: how do we balance the desire for open access and sharing with the need to compensate creators for their work?

As we mark the 50th anniversary of Gates' open letter, it serves as a reminder that the challenges facing today's software industry—piracy, monetization, open vs. closed development—have deep historical roots. The young programmer who complained about hobbyists stealing his software went on to shape not just Microsoft, but the entire paradigm of how we think about, buy, and use software.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion