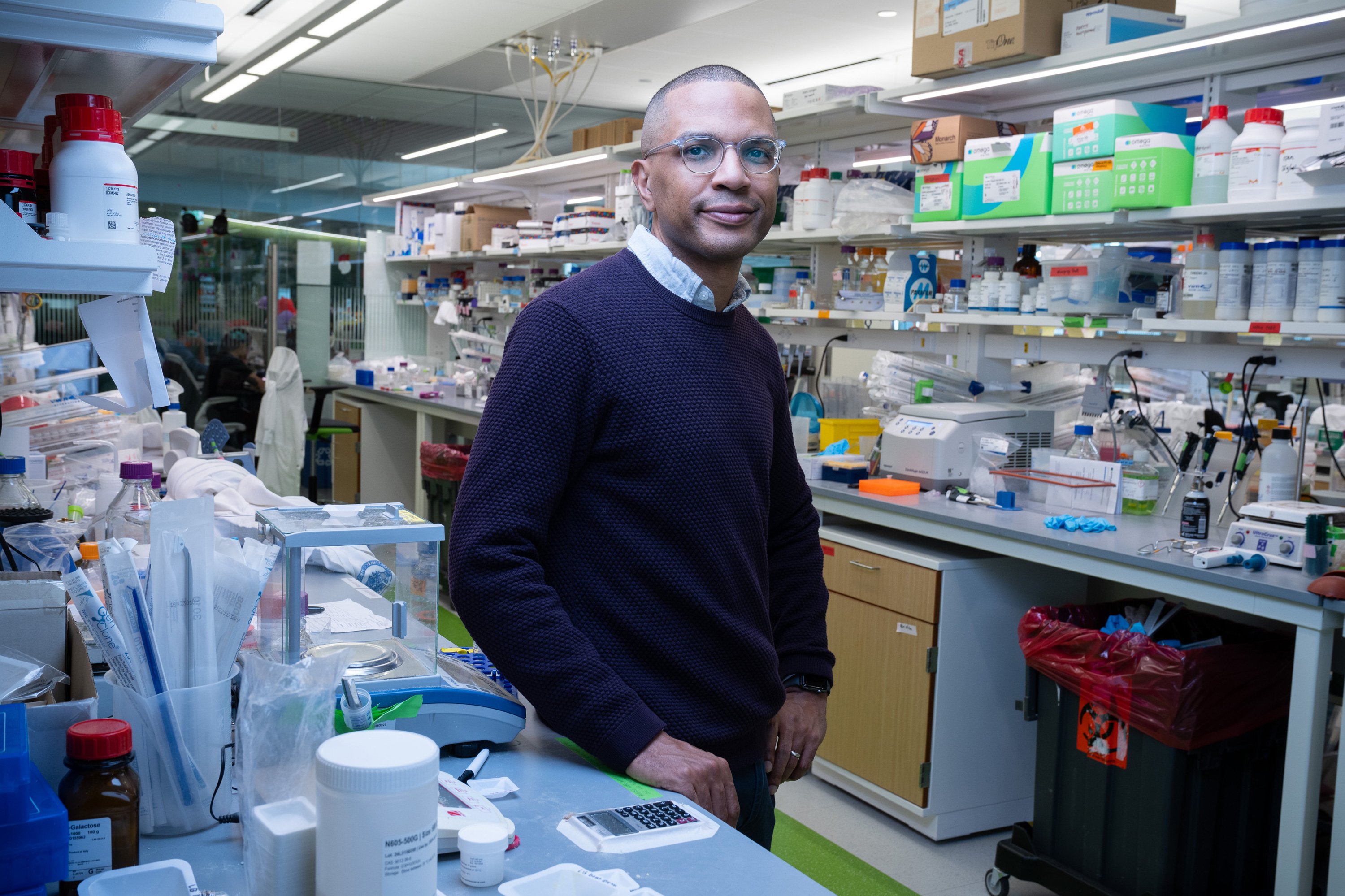

MIT biological engineer Bryan Bryson is applying an engineering mindset to the ancient scourge of tuberculosis, developing novel measurement tools to identify the bacterial proteins that could form the basis of a more effective vaccine for the disease that still kills over a million people annually.

The problem of tuberculosis is, at its core, an engineering challenge. For millennia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade the human immune system, making it one of the most successful human pathogens in history. To combat it, we need to understand its systems, find their weaknesses, and design a solution. This is the perspective Bryan Bryson, an associate professor in MIT's Department of Biological Engineering, brings to his research.

"Here is a pathogen that has probably killed more people in human history than any other pathogen, so you want to learn how to kill it," says Bryson. "That has really been the core of our scientific mission since I started my lab. How does the immune system see this bacterium and how does the immune system kill the bacterium? If we can unlock that, then we can unlock new therapies and unlock new vaccines."

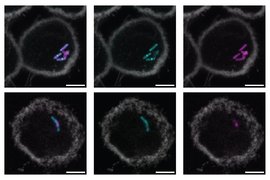

Bryson's lab focuses on a critical step in the immune response: the presentation of bacterial antigens on the surface of infected host cells. For an immune cell to recognize and destroy an infected cell, it must first see a piece of the pathogen displayed on that cell's surface. M. tuberculosis produces over 4,000 proteins, but only a small fraction of these are ever presented to the immune system. Identifying which ones are presented is the key to designing a targeted vaccine.

"To me, making a better TB vaccine comes down to a question of measurement, and so we have really tried to tackle that problem head-on," Bryson explains. "The mission of my lab is to develop new measurement modalities and concepts that can help us accelerate a better TB vaccine."

An Engineering Path to Immunology

Bryson's approach is shaped by a lifetime of engineering thinking. His great-grandfather worked on the Panama Canal, and his grandmother loved to build things. As a child in Miami, he built robots from Styrofoam cups and light bulbs. When he arrived at MIT, he initially considered aeronautics and astronautics, dreaming of spacesuit design. A pivotal piece of advice from a summer internship mentor—"study something that will let you have a lot of options"—led him to switch to mechanical engineering with a bioengineering track.

His trajectory changed in the lab of Linda Griffith, a professor of biological and mechanical engineering. Working on microfluidic devices to grow liver tissue, Bryson realized he was fascinated not just by the engineering, but by the cells themselves and their behavior. This experience cemented his path to a PhD in biological engineering, where he studied cell signaling in diseases like cancer and diabetes.

It was during his postdoctoral work with Sarah Fortune at the Harvard School of Public Health that he turned his focus to infectious diseases. Fortune, who studies tuberculosis, instilled in him a desire for transformative solutions. "That postdoc really taught me how to think bravely about what you could do if you were not limited by the measurements you could make today," Bryson recalls. "What are the problems we really need to solve? There are so many things you could think about with TB, but what’s the thing that’s going to change history?"

Identifying the Right Targets

Since joining the MIT faculty in 2018, Bryson's lab has made significant progress in identifying which TB proteins are presented to the immune system. Their research has revealed that many of these key antigens belong to a class of proteins known as type 7 secretion system substrates. M. tuberculosis expresses about 100 of these proteins, but the specific subset displayed on infected cells varies from person to person, depending on genetic background.

By studying blood samples from individuals with diverse genetic backgrounds, Bryson's team has identified the TB proteins displayed by infected cells in approximately 50 percent of the human population. They are now working to characterize the remaining 50 percent. "Once those studies are finished, I’ll have a very good idea of which proteins could be used to make a TB vaccine that would work for nearly everyone," Bryson says.

This population-level approach is crucial. The current TB vaccine, the BCG vaccine, is a weakened version of a bacterium that causes TB in cows. While widely administered, it offers poor protection against pulmonary TB in adults. A new vaccine based on the specific proteins Bryson's lab is identifying could provide more targeted and effective immunity.

The MIT Ethos and the Path Forward

Bryson credits his mother, who raised four sons on her own, for instilling a resilient and optimistic mindset. "She made it look so flawless. She instilled a sense of ‘you can do what you want to do,’ and a sense of optimism," he says. This attitude aligns with what he sees as the core engineering ethos at MIT. "The engineer ethos of MIT is that yes, this is possible, and what we’re trying to find is the way to make this possible. I think engineering and infectious disease go really hand-in-hand, because engineers love a problem, and tuberculosis is a really hard problem."

The challenges are substantial. Tuberculosis still kills more than a million people every year. Developing a new vaccine is a long, complex process. Bryson estimates that once the target proteins are fully identified, his team could begin designing and testing a vaccine in animals, with the goal of reaching clinical trials in about six years.

Beyond the lab, Bryson brings his engineering mindset to his role as an associate head of house at Simmons Hall, where he conducts "ice cream study breaks." Using an ice cream machine he's had since 2009, he creates nontraditional flavors for dorm residents—passion fruit, jalapeno strawberry, toasted marshmallow. It's a lighter counterpoint to the immense weight of the disease he studies daily, but the underlying principle is the same: understanding a system (in this case, flavor chemistry) to create a desired outcome.

Bryson's work exemplifies a growing trend in biomedical research: the application of engineering principles—systems thinking, precise measurement, and targeted design—to complex biological problems. By treating the immune system as a system to be understood and the pathogen as a system to be disrupted, he is working to transform our approach to one of humanity's oldest and most persistent diseases. The goal is not just incremental improvement, but a fundamental shift in how we fight tuberculosis, moving from broad, partially effective measures to a precisely engineered solution.

Related Links:

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion