A developer chronicles using generative AI models and coding agents to create a massive isometric pixel-art map of New York City, revealing both the transformative potential and current limitations of AI in creative software development.

Standing on the 13th floor balcony of Google's New York office, looking out at Lower Manhattan, the author found themselves contemplating the future of creativity through the lens of AI models like Nano Banana and Veo. Rather than engaging in the familiar debates about AI's impact on art or economics, they focused on a more practical question: What is now possible that was impossible before?

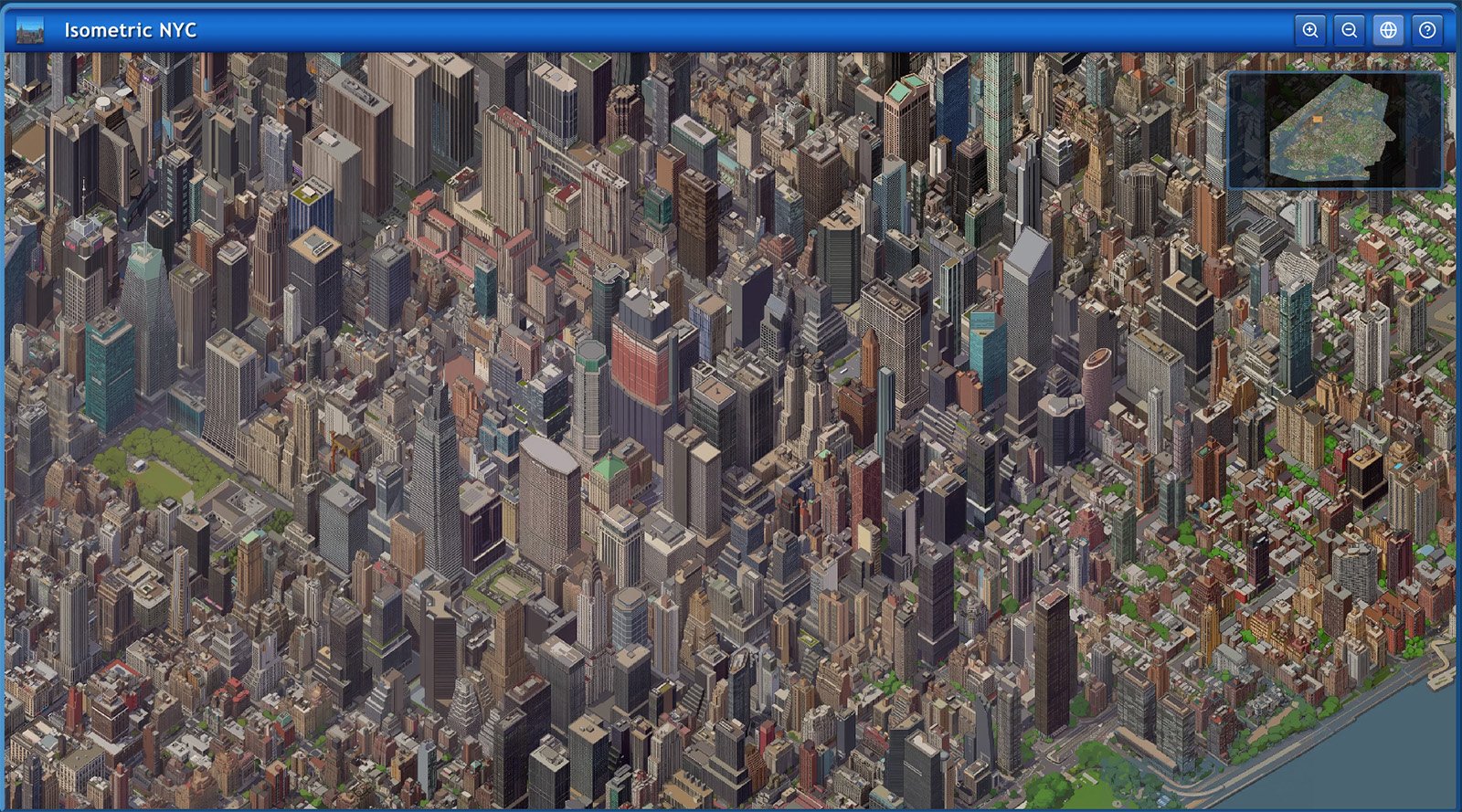

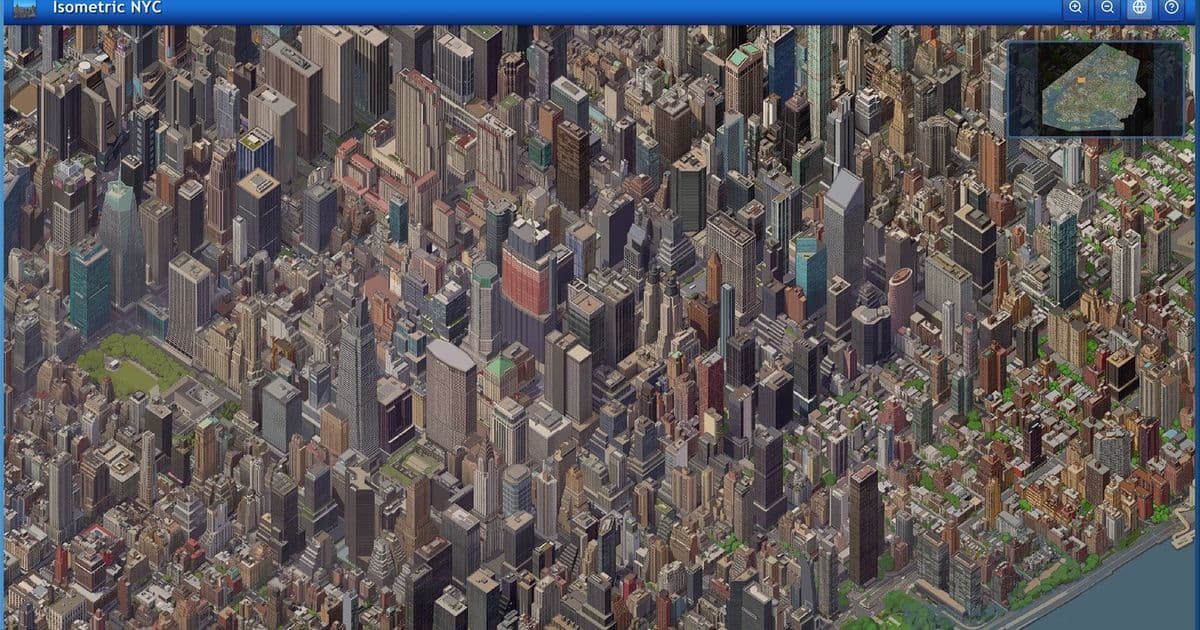

This question led to an ambitious project: creating a giant isometric pixel-art map of New York City in the nostalgic style of late-90s/early-2000s world-building games like SimCity 2000. The project would serve as both a creative endeavor and a technical experiment to push the limits of the latest generative models and coding agents. The author collectively refers to these AI coding tools as "the agent," having switched between Claude Code, Gemini CLI, and Cursor (using both Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3 Pro) throughout the process.

The Initial Approach: City Data and Geometry

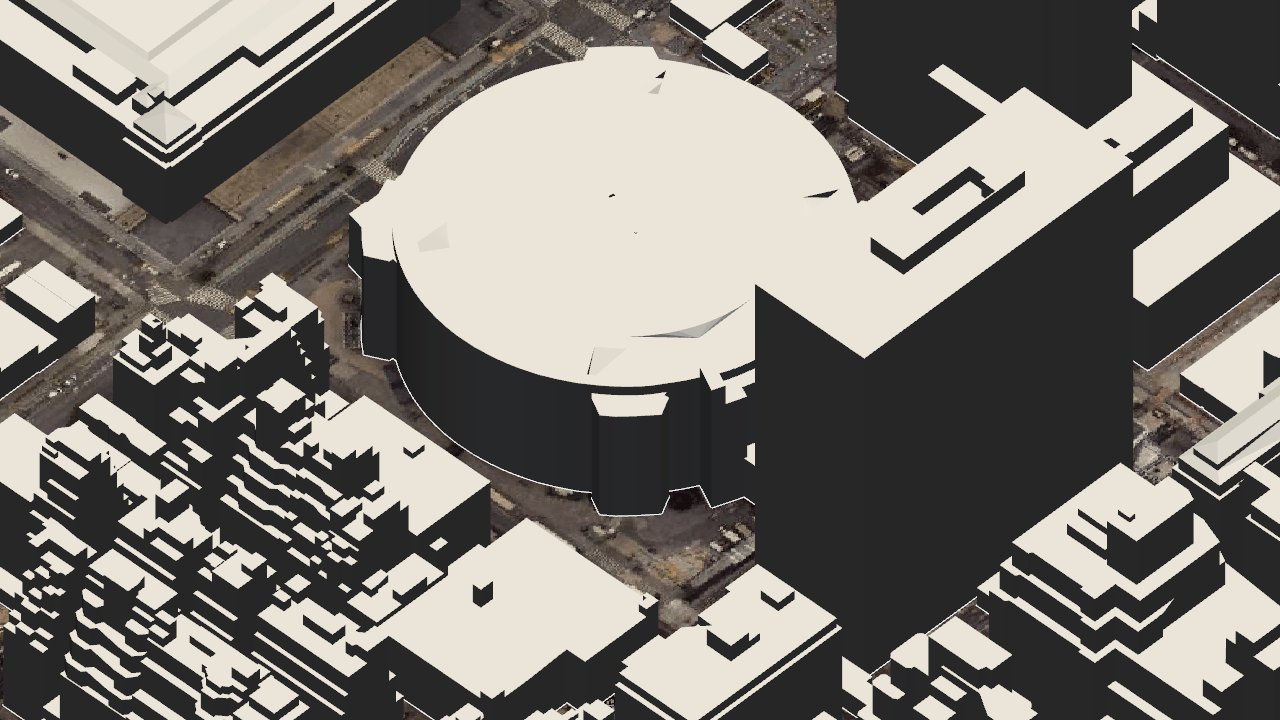

The project began with a strategy to use 3D CityGML data from sources like NYC 3D, 3DCityDB, and NYC CityGML to render a "whitebox" view of individual tiles. Despite having no prior experience with CityGML data or GIS systems—fields notoriously complex and finicky—the author found that working with an AI agent dramatically accelerated the learning process.

With back-and-forth guidance from the agent, the author quickly set up a renderer that could output isometric (orthographic) renders of real city geometry superimposed on satellite imagery. This initial success demonstrated a key pattern: the agent could handle coordinate projection systems and geometry labeling schemas that would typically require extensive domain knowledge.

However, when testing with Nano Banana Pro, inconsistencies emerged between the whitebox geometry and top-down satellite imagery. The model struggled with hallucinations when resolving these differences, leading the author to explore alternative approaches.

Google Maps 3D Tiles: A Better Foundation

Research revealed that the Google Maps 3D tiles API offered precisely what was needed: accurate geometry and textures within a single renderer. The challenge became downloading geometry for specific tiles, rendering them in a web renderer with an orthographic camera, and exporting tiles that precisely matched existing whitebox renders.

Again, the agent proved capable of building this infrastructure, creating a system that could generate isometric web renders of city geometry directly from Google Maps 3D tiles. This shift from CityGML data to Google's 3D tiles provided more consistent and reliable geometry, forming the foundation for the subsequent image generation pipeline.

Image Generation: Nano Banana's Limitations

With the geometry pipeline established, the author turned to generating pixel-art tiles using Nano Banana Pro. After prompt engineering efforts, the model could generate tiles in the preferred style with some reliability, but several critical issues emerged:

Consistency Problems: Even with reference images, examples, and extensive prompt engineering, Nano Banana struggled to maintain consistent style across generations. The author estimated a success rate of only 50%, insufficient for the estimated 40,000 tiles required for the complete NYC map.

Cost and Speed: Nano Banana proved too slow and expensive for large-scale generation. The cost and processing time made generating all necessary tiles impractical.

These limitations prompted a strategic pivot: fine-tuning a smaller, faster, and more cost-effective model.

Fine-Tuning Qwen/Image-Edit

The author opted to fine-tune a Qwen/Image-Edit model using the oxen.ai service. Creating a training dataset of approximately 40 input/output pairs, the fine-tuning process took about 4 hours and cost approximately $12. The results were promising—the fine-tuned model could generate tiles in the preferred style with improved consistency.

The Infill Strategy for Seamless Generation

To generate a seamless map, the author implemented an "infill" strategy. Rather than generating complete 1024x1024 tiles from scratch, the system created a dataset with input images where portions of the target image were masked out. This approach allowed for staggered generation, where new tile content could be generated adjacent to already-completed tiles, ensuring seamless transitions.

The Qwen/Image-Edit model proved capable of learning this infill task, demonstrating that fine-tuned models could handle more complex generation workflows beyond simple text-to-image prompts.

Building the End-to-End Generation System

Recognizing that software engineering best practices remain critical even when code is generated by agents, the author designed an end-to-end generation application. The system was built around several key principles:

- Small, isolated changes with immediate testing

- Domain modeling and data storage as critical components

- Simple, boring technology over complex solutions

- Iteration over upfront design

The resulting system featured:

- A schema centered around 512x512 pixel "quadrants"

- A SQLite database storing all quadrants with coordinates and metadata

- A web application for displaying generated quadrants and selecting which to generate next

This application became the central hub for managing the generation process, allowing for progressive tile creation and systematic tracking of progress.

The Power of Micro-Tools

One of the most transformative aspects of working with AI agents was the ability to create micro-tools on demand. The author built numerous small utilities that would have been impractical to develop manually:

- Bounds App: Visualized generated and in-progress tiles superimposed on a real NYC map, evolving into a full boundary polygon editor for determining export tile edges

- Water Classifier: Determined whether quadrants partially or completely contained water

- Training Data Generator: Created additional training data for the Qwen/Image-Edit model

A pattern emerged: CLI tools were easiest for the agent to build, test, and debug. When integration into larger systems became necessary, the agent could abstract the functionality into shared libraries with minimal effort.

Confronting Edge Cases: Water and Trees

As the project progressed, the author encountered the classic software development challenge: the last 10% of work consuming 90% of the time. Two particular edge cases proved especially problematic: water and trees.

New York City's geography presented significant challenges. The Hudson and East Rivers, New York Harbor, Jamaica Bay, and the Long Island Sound created extensive water features with complex topography including islands, sand bars, and marshlands. The fine-tuned models struggled with these elements despite numerous retraining attempts.

Trees proved even more problematic—a nearly perfect pathological use case for current image models. The fundamental issue was the difficulty in separating structure from texture, a classic challenge in image model training.

The author developed several micro-tools to address these issues:

- Automatic color-picker based water correction in the generation app

- Custom prompting with negative prompting and model-swappability

- Export/import functionality to Affinity (photo editing software) for manual fixes

Despite these tools, manual intervention remained necessary. The author ultimately invested significant time in manually correcting edge cases, accepting that the difference between "good enough" and "great" often comes down to the care and attention invested in the work.

Scaling Up: From Platform to Self-Hosted

While oxen.ai provided excellent abstraction for fine-tuning and deployment, inference costs and speed became limiting factors for scaling to the full NYC map. The author exported model weights to rented GPU+VMs using Lambda AI, setting up an inference server that could be accessed from the web generation application.

This transition represented a significant efficiency gain. Running multiple models in parallel on an H100 GPU, the system could generate over 200 tiles per hour at less than $3 per hour, making the project tractable both in terms of time and cost.

The process highlighted how AI agents have transformed model deployment. What previously required hours or days of painful debugging now took minutes. The author could focus on specifying generation queue behavior and domain-specific logic without concerning themselves with implementation details.

The Challenge of Automation

Despite successful scaling, automating the generation process proved difficult. Creating an efficient tiling algorithm that avoided seams presented challenges that the agents struggled to solve reliably.

The generation rules were conceptually simple: no quadrant could be generated such that a seam would appear. However, specifying the generation logic, testing it, and making it useful for higher-level planning algorithms required significant iteration. The author eventually developed a workable system with manual guidance, but the process revealed that some algorithms remain irreducibly complex, and current AI models struggle to understand core logic through specification documents alone.

Building the Final Application

With tile generation operational, the author turned to building the final application for displaying generated tiles at all zoom levels. This seemingly simple task became one of the more difficult challenges for the coding agents.

Drawing on experience building custom tiled gigapixel image viewers at Google Brain, the author selected the open-source OpenSeaDragon library but still faced numerous challenges with zoom/coordinate space and caching/performance issues. High-performance graphics with manual touch interaction proved particularly difficult for current browser control tools.

Key Takeaways

Cheap, Fast Software Transforms Development

The ability to build tools at the speed of thought represents a fundamental shift. Ideas that would have taken days or weeks to implement can now be created in minutes. This is especially valuable for throwaway tools—debuggers, visualizers, script runners—where code quality matters less than functionality.

The Unix philosophy of small, modular programs becomes even more valuable in this context. Composable tools that do one thing well can be easily combined into larger applications, and the low cost of code generation makes this approach highly effective.

Image Models Lag Behind Text/Code Generation

A significant gap exists between text/code generation and image generation. While coding agents can run code, read stack traces, see errors, and correct themselves through tight feedback loops, image models lack this capability. They cannot reliably assess their own outputs for issues like seams or incorrect textures, making automated quality assurance impossible.

Fine-tuning remains challenging. Models often learn in counterintuitive ways, requiring deep ML theory knowledge and strong intuitions about model implementations. The author notes that while humans excel at contrastive learning (learning from mistakes) and continuous learning, most AI models are trained purely via association and remain stateless.

The Edit Problem

Generative image models lack reliable editing interfaces. With code, you can point to specific lines and make targeted changes. With images, models must regenerate entire images from scratch via diffusion rather than making localized edits. There's no reliable way to reference specific elements ("copy that tree") or annotate images for editing. Masking and transparency features remain primitive.

AI as a Creative Tool

The project demonstrates AI's ability to eliminate drudgery from creative work. The author spent a decade as an electronic musician, spending thousands of hours on tedious tasks like adjusting audio clips by milliseconds. Much of creative work involves this kind of grind rather than pure creative decisions.

AI agents unlock previously unimaginable creative projects by handling scale. Creating pixel art for every building in New York City by hand would require a large team and extensive time. With AI assistance, a single developer can undertake such ambitious projects.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the author remains optimistic about AI and creativity precisely because it commoditizes easy tasks. When pushing a button can generate content, that content becomes a commodity with minimal value. The differentiator becomes the love, care, and unique vision that creators bring to their work—elements that AI cannot replicate.

The Isometric NYC project stands as both a technical achievement and a philosophical statement: AI tools don't replace creativity but rather expand its boundaries, allowing creators to focus on vision and decisions rather than tedious execution. The map continues to grow, tile by tile, as a testament to what becomes possible when human creativity meets AI capability.

For those interested in the technical details, the author's process is documented in a series of task files including tasks/004_tiles.md, tasks/005_oxen_api.md, and tasks/013_generation_app.md, with the complete project available on GitHub.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion