MIT research scientist Judah Cohen combines decades of Arctic atmospheric diagnostics with modern machine learning to extend weather prediction lead times from weeks to months, winning first place in a major forecasting competition.

Every autumn, as the Northern Hemisphere moves toward winter, Judah Cohen starts to piece together a complex atmospheric puzzle. Cohen, a research scientist in MIT's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, has spent decades studying how conditions in the Arctic set the course for winter weather throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. His research dates back to his postdoctoral work with Bacardi and Stockholm Water Foundations Professor Dara Entekhabi that looked at snow cover in the Siberian region and its connection with winter forecasting.

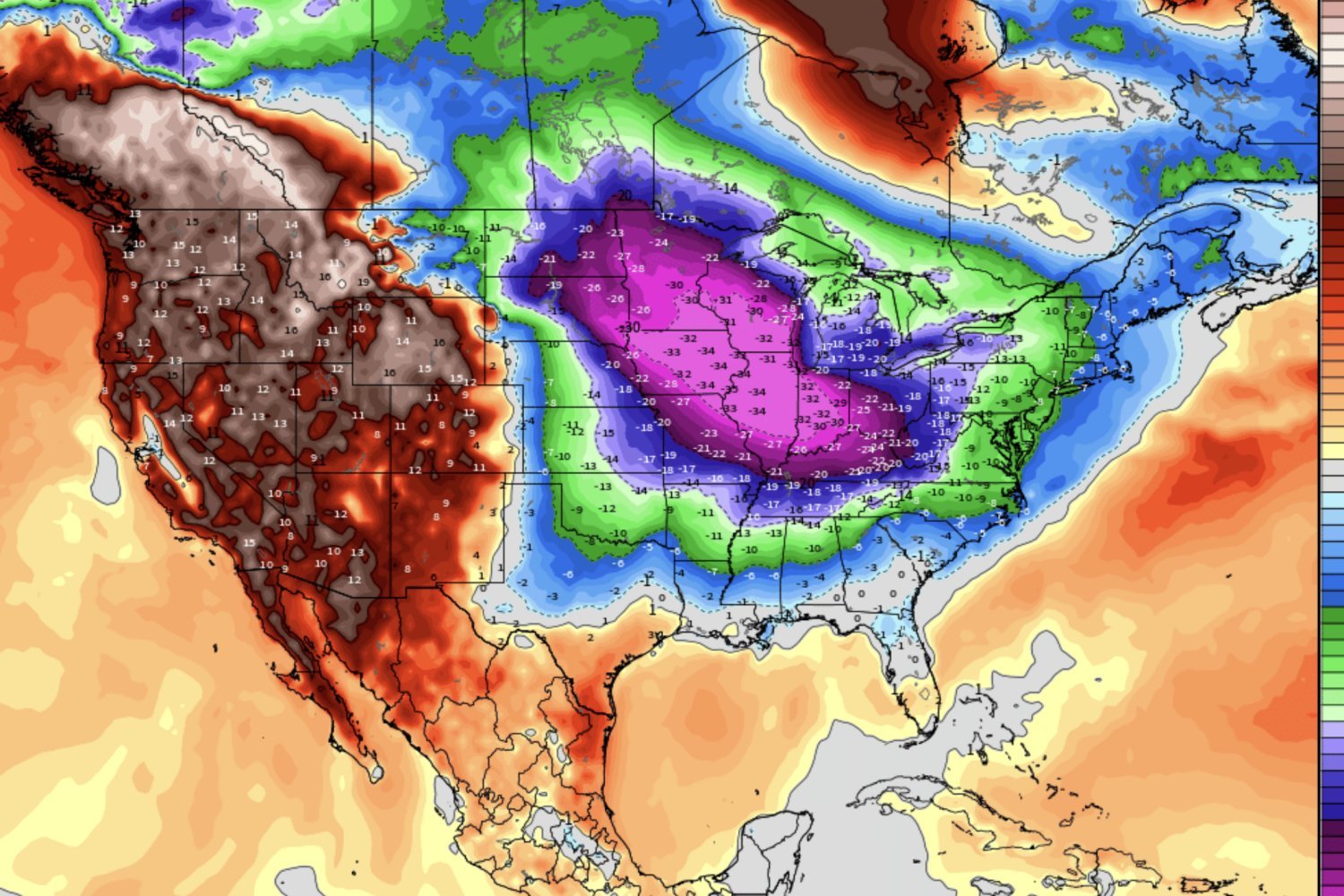

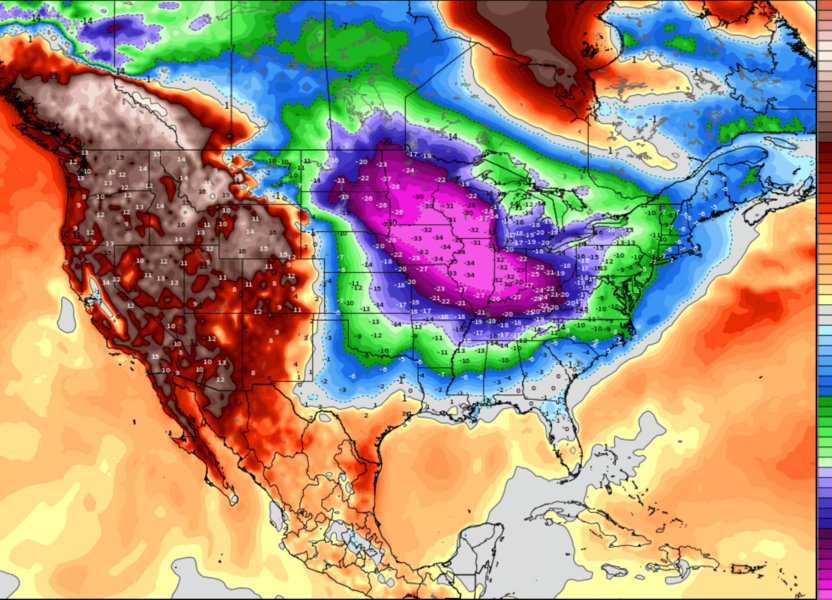

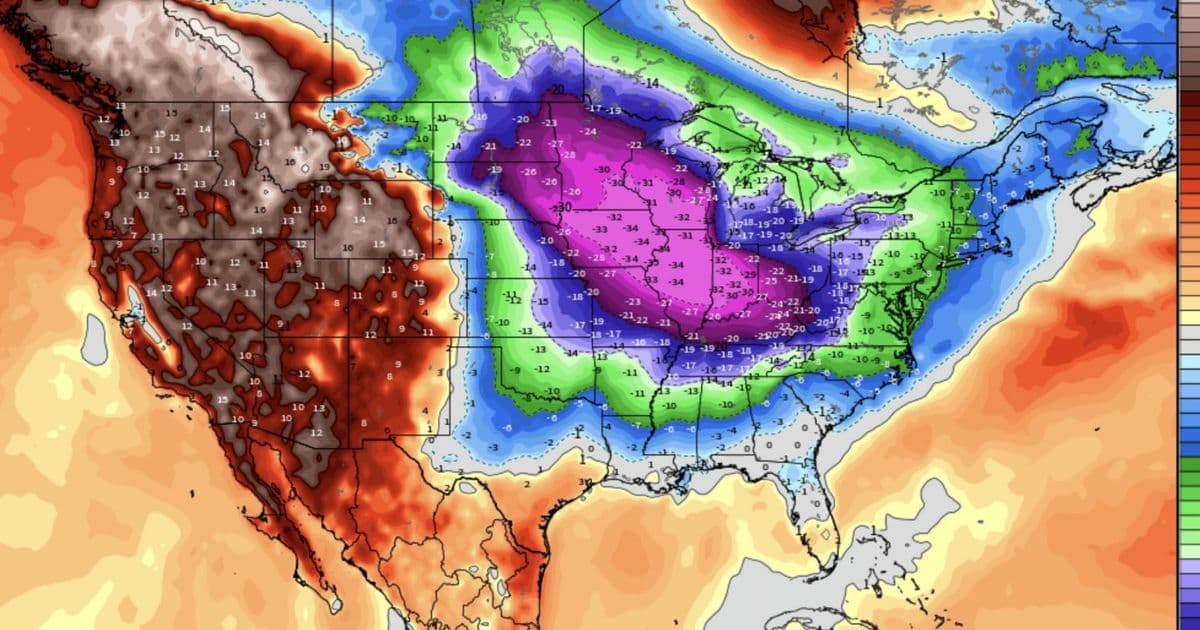

The 2025-26 winter season highlights a convergence of traditional Arctic diagnostics and new artificial intelligence tools. Cohen's outlook for this season shows indicators emerging from the Arctic that could shape weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere. The timing is significant because traditional climate drivers are unusually quiet this year, making Arctic signals more critical for accurate predictions.

When ENSO Steps Back, Arctic Signals Step Forward

Winter forecasts traditionally rely heavily on El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) diagnostics, which describe tropical Pacific Ocean and atmosphere conditions that influence global weather. However, Cohen notes that ENSO is relatively weak this year. "When ENSO is weak, that's when climate indicators from the Arctic become especially important," he explains.

Cohen monitors several high-latitude diagnostics for subseasonal forecasting:

- October snow cover in Siberia: The extent and timing of snow cover affects atmospheric pressure patterns

- Early-season temperature changes: Initial cold snaps can trigger cascading atmospheric effects

- Arctic sea-ice extent: Reduced ice cover changes heat flux between ocean and atmosphere

- Polar vortex stability: The strength and position of this high-altitude wind system determines how far cold Arctic air penetrates southward

"These indicators can tell a surprisingly detailed story about the upcoming winter," Cohen says.

Siberian Snow: A Consistent Predictor

One of Cohen's most reliable data points comes from October weather in Siberia. This year, while the Northern Hemisphere experienced an unusually warm October overall, Siberia was colder than normal with an early snow fall.

Cold temperatures paired with early snow cover tend to strengthen the formation of cold air masses that can later spill into Europe and North America. These patterns are historically linked to more frequent cold spells later in winter. The mechanism works through a chain reaction: early snow increases surface reflectivity (albedo), which cools the lower atmosphere, which strengthens high-pressure systems, which eventually influences the jet stream's path.

Additional indicators this year include warm ocean temperatures in the Barents–Kara Sea and an "easterly" phase of the quasi-biennial oscillation. Together, these suggest a potentially weaker polar vortex in early winter. When this disturbance couples with surface conditions in December, it leads to lower-than-normal temperatures across parts of Eurasia and North America earlier in the season.

AI Subseasonal Forecasting: Bridging the Two-to-Six Week Gap

While AI weather models have made impressive strides in short-range (one-to-10-day) forecasts, these advances have not yet fully applied to longer periods. Subseasonal prediction covering two to six weeks remains one of the toughest challenges in meteorology. This timeframe is too far out for traditional numerical weather prediction models to maintain accuracy, yet too short for climate models to capture meaningful patterns.

A team of researchers working with Cohen won first place for the fall season in the 2025 AI WeatherQuest subseasonal forecasting competition, held by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The challenge evaluates how well AI models capture temperature patterns over multiple weeks, where forecasting has been historically limited.

The winning model combined machine-learning pattern recognition with the same Arctic diagnostics Cohen has refined over decades. The system demonstrated significant gains in multi-week forecasting, surpassing leading AI and statistical baselines. "If this level of performance holds across multiple seasons, it could represent a real step forward for subseasonal prediction," Cohen says.

The model also detected a potential cold surge in mid-December for the U.S. East Coast much earlier than usual, weeks before such signals typically arise. The forecast was widely publicized in the media in real-time. If validated, Cohen explains, it would show how combining Arctic indicators with AI could extend the lead time for predicting impactful weather.

"Flagging a potential extreme event three to four weeks in advance would be a watershed moment," he adds. "It would give utilities, transportation systems, and public agencies more time to prepare."

How the AI Enhances Traditional Methods

The integration of machine learning with Arctic diagnostics represents a hybrid approach. Traditional statistical methods rely on known teleconnections—established relationships between distant weather phenomena. AI pattern recognition can identify subtle, non-linear relationships that might be missed by conventional analysis.

For example, the AI might detect that certain combinations of sea-ice extent, Siberian snow cover, and polar vortex behavior correlate with specific temperature anomalies three weeks later. These patterns might be too complex or counterintuitive for human analysts to spot consistently, but machine learning can process vast datasets to find reliable signals.

The ECMWF competition specifically tested temperature pattern prediction across multiple weeks. This is crucial because temperature anomalies drive many downstream effects: energy demand, agricultural impacts, transportation delays, and extreme weather preparedness.

What This Winter May Hold

Cohen's model shows a greater chance of colder-than-normal conditions across parts of Eurasia and central North America later in the winter, with the strongest anomalies likely mid-season. "We're still early, and patterns can shift," Cohen says. "But the ingredients for a colder winter pattern are there."

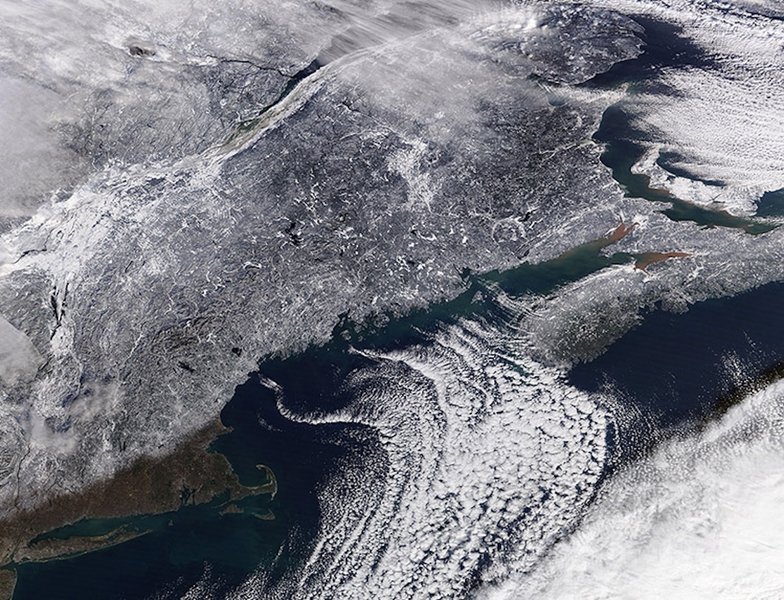

The satellite imagery shows the northeastern United States, including Cape Cod and Long Island, which could be affected by the cold surge patterns Cohen's model predicts. These regions often experience amplified effects when Arctic air masses interact with relatively warm Atlantic waters.

As Arctic warming speeds up, its impact on winter behavior is becoming more evident. This might seem counterintuitive—warming Arctic leading to colder winters elsewhere—but the mechanism involves disrupted atmospheric circulation. A warmer Arctic reduces the temperature gradient between polar and mid-latitude regions, which can weaken and shift the jet stream, allowing cold air to escape its usual polar confinement.

Practical Applications and Broader Implications

Understanding these connections is increasingly important for energy planning, transportation, and public safety. Utilities need accurate winter forecasts to manage heating fuel supplies and electricity generation. Transportation agencies must prepare for snow and ice removal. Public health officials monitor cold-related risks.

Cohen's work shows that the Arctic holds untapped subseasonal forecasting power, and AI may help unlock it for time frames that have long been challenging for traditional models. The research bridges atmospheric science with practical applications, demonstrating how academic insights can translate into actionable intelligence.

In November, Cohen even appeared as a clue in The Washington Post crossword, a small sign of how widely his research has entered public conversations about winter weather. "For me, the Arctic has always been the place to watch," he says. "Now AI is giving us new ways to interpret its signals."

Looking Ahead

Cohen will continue to update his outlook throughout the season on his blog. The real test of the AI-enhanced approach will be its performance across multiple seasons and varying climate conditions. If the hybrid model continues to outperform traditional methods, it could represent a significant advancement in subseasonal forecasting capability.

The research also demonstrates a broader pattern in meteorology: as computational power increases and machine learning techniques mature, the integration of domain expertise with AI is yielding practical results. Cohen's decades of Arctic research provided the foundation, while AI provided the tools to extract more value from that knowledge.

This approach could extend beyond winter weather to other subseasonal forecasting challenges, such as predicting monsoon onset, drought development, or tropical cyclone activity weeks in advance. The key is combining physical understanding with computational pattern recognition.

The Arctic remains a complex and rapidly changing region. Its influence on mid-latitude weather will only grow as the climate evolves. Tools that can decode these signals weeks in advance will become increasingly valuable for societies adapting to a changing climate.

Related Resources:

- Judah Cohen's Department Profile - MIT Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

- AI WeatherQuest Competition - European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

- Cohen's Winter Weather Blog - Regular seasonal updates and analysis

- MIT Climate Modeling Initiative - Related research on climate prediction and modeling

Technical References:

- Polar Vortex Monitoring - NOAA Climate Prediction Center

- Arctic Sea Ice Index - National Snow and Ice Data Center

- Subseasonal Experiment (SubX) - NOAA/EMC subseasonal forecasting project

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion