Building a scalable RBAC system requires more than just a roles table. This article breaks down the core entities, relationships, and design trade-offs needed to model real-world organizational structures in software, from the high-level architecture down to the critical decision of separating permissions into their own table.

Every organization uses a set of SaaS products for their daily operations. Every such product is responsible for sheltering data and performing operations at large scale. So there should be appropriate checks as to who can do what with the data. And that's where Role-Based Access Control comes into play.

A Bit About RBAC

Before we dig in, a bit of an explainer will help us start off at the same page. RBAC is a 1-1 mirror of how organizations work IRL. You as an employee will have a job role, and with your role, comes responsibilities and permissions. An employee who is an accountant will have access to the debit/credit book of the company. A DevOps engineer will be heading the pipeline development of the products. And so on.

Similarly in SaaS products, to control the access of users to specific actions and data, we put RBAC in place. Project admins (often the person who signed up for the product) create teams, roles, and assign them to certain users within the product.

Whom This Article Is For

Unconventional way to start, but since I'm writing this to address a very niche, I would like to set the expectations for the readers in here. This article is not for you if:

- You are looking for a Node-based RBAC implementation

Yes, that's just about it. But, you should read it if you:

- Are a beginner and trying to grasp the fundamentals of RBAC

- Are trying to debug what went wrong in your design, or, attempting to improve your design

- Need a handbook for initial steps

- Want to please your seniors with a weekend blog reflection

RBAC Designs

The most basic form of RBAC system will almost always have these entities in some form or the other:

- Organization: The unit under which users, resources, and roles reside. This is where the action takes places.

- User: The actors, using the platform and taking actions.

- Resource: Items which are being acted upon by the users. It can be docs, VMs, databases, etc. These are what we protect using roles.

- Role: The gatekeeper, preventing/allowing users' access to resources.

- Permission: Associated with roles, define what a role will permit its users to do.

- User Group: Optionally present in infrastructures with massive number of resources. It associates with multiple roles and users.

The Design

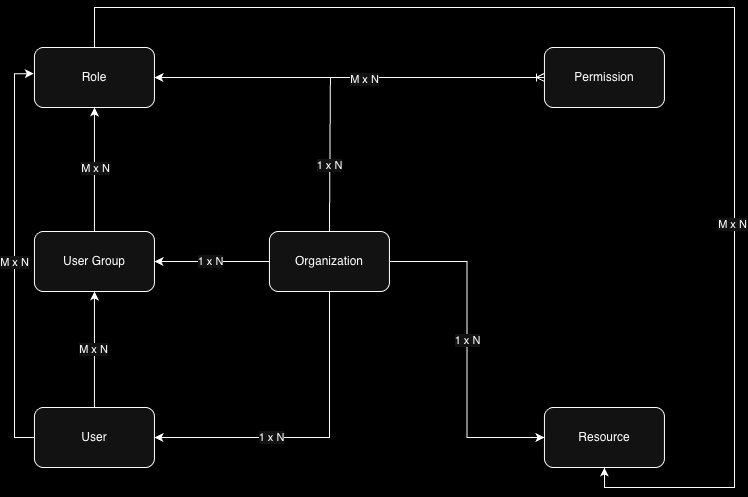

An organization is the host. Everything in our infrastructure (except permissions) are tied up with the organization.

- An organization can have multiple users → 1 x N

- An organization can have multiple roles → 1 x N

- An organization can have multiple resources → 1 x N

- An organization can have multiple user groups → 1 x N

- A role can be associated with multiple permissions, and permission can be associated with multiple roles → M x N

- A role can be associated with multiple users, and a user can be associated with multiple roles → M x N

- A role can be associated with multiple resources, and a resource can be tied up with multiple roles → M x N

- A role can be tied up with multiple user groups, and a user group can be tied up with multiple roles → M x N

- A user can be tied up with multiple user groups, and a user group can be tied up with multiple users → M x N

High-level Diagram

The core of the system is the Organization entity. All other entities are scoped within it. This is a critical design decision for multi-tenant SaaS applications. It ensures data isolation and simplifies queries, as you can always filter by organization_id.

The relationships are many-to-many (M x N) where flexibility is required. For instance, a single user can be a Developer on one project and a Viewer on another within the same organization. This is modeled by a join table between Users and Roles, which itself is scoped to an Organization.

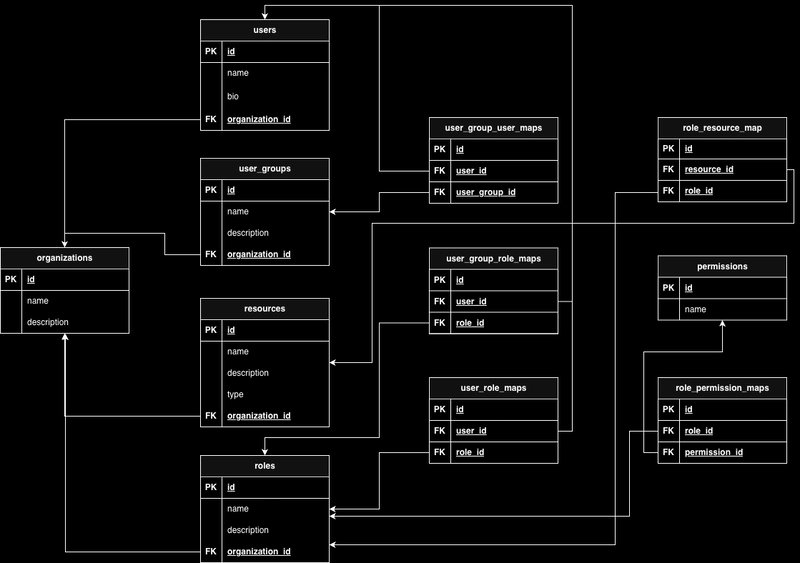

Detailed Diagram

Here's a more granular look at the database schema design:

Core Tables:

organizations(id, name, created_at)users(id, email, organization_id, created_at)resources(id, name, type, organization_id, created_at)roles(id, name, description, organization_id, created_at)permissions(id, name, description, resource_type, action)

Join Tables (The Glue):

user_roles(user_id, role_id, organization_id) - Links users to their roles.role_permissions(role_id, permission_id) - Defines what a role can do.role_resources(role_id, resource_id) - (Optional) Scopes a role to specific resources. This is useful for granular control, e.g., a "Project Admin" role for one project but not another.user_groups(id, name, organization_id)user_group_users(user_group_id, user_id, organization_id)user_group_roles(user_group_id, role_id, organization_id) - This allows assigning roles to a group, which then propagates to all users in that group.

Design Outcomes and Trade-offs

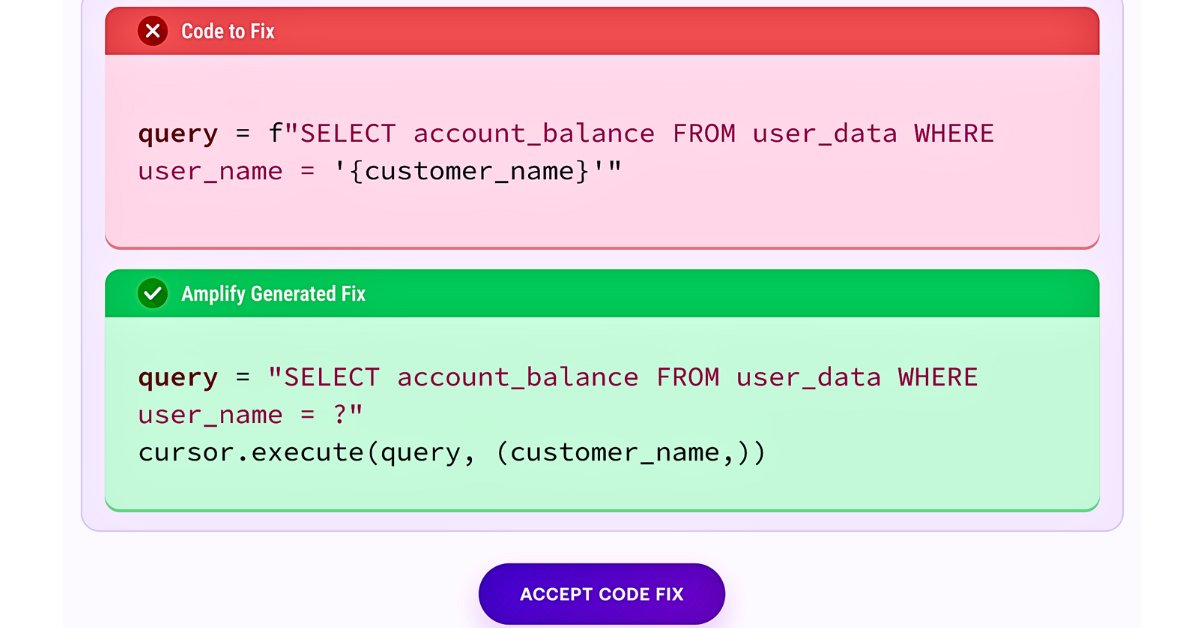

Having a separate table for permissions is purely a design choice, and not a mandate. However, it's a powerful one.

Why separate the permissions table?

- Centralized Definition: Permissions like

create:document,read:database,delete:vmare defined once and reused across multiple roles. This avoids duplication and makes it easier to audit what permissions exist in the system. - Scoping by Resource Type: Having a separate permission table allows you to scope permissions for specific resources. For example, the role

ORGANIZATION_ADMINwon't be applicable to aDocumentresource. You could have an optional list of acceptable/unacceptable resource types per permission. - Dynamic Role Creation: Admins can create new roles by simply selecting from a predefined list of permissions, without needing to hard-code logic for each new role.

The Trade-off: Flexibility vs. Complexity

We chose binary join tables (user_roles, role_permissions) instead of a higher-order join table. A higher-order table might look like user_role_permissions (user_id, role_id, permission_id). This seems simpler but is far less flexible.

- Binary Join Tables (Our Choice): Provide maximum flexibility. You can change a role's permissions without affecting users. You can reassign a user's roles without redefining permissions. The cost is slightly more complex queries (requiring joins) and some data repetition (the same permission might be linked to multiple roles).

- Higher-Order Join Tables: Can be faster for direct permission checks (a single lookup). However, they create tight coupling. Changing a permission for a role would require updating every user in that role, which is inefficient and error-prone.

User Groups: A Necessary Abstraction

A user can be tied up with both roles and user groups simultaneously. User groups are never tied with resources directly. Their sole purpose is to aggregate users and assign roles at a group level. This is crucial for large organizations where managing permissions for hundreds of users individually is untenable. For example, all "Backend Engineers" can be in a group, and the "Backend Developer" role is assigned to that group.

Organizational Roles vs. Resource-Specific Roles

There can be roles that may not be tied with any resources at all. For example, a role having ORGANIZATION_ADMIN would imply administrative access over the organization, and hence won't have any resource mapping. This is an important distinction. Some permissions are global (organization-level), while others are scoped to a specific resource (document-level, project-level). Your schema should support both.

The Principle of Least Privilege

Usually, this is where I conclude my blogs with a Conclusion, but I thought about making this section a bit more informative. This is not related to how you should implement an RBAC system, but how you should use it properly.

The Principle of Least Privilege states that actors should be granted the least possible set of permissions required for it to operate efficiently.

Consider you have a CI/CD pipeline that will fetch your code from your SCM, build an artifact, and deploy it to AWS Lambda. So collectively, it will require the following permissions:

- Read repository on SCM

- Pull code from SCM

- Push deployment to AWS Lambda

This is how you build a restrictive system with the least access.

Why does this matter?

Say that your deployment script gets a new change that was pushed unchecked. If the deployment role has overly broad permissions (e.g., *:* on AWS), this can now affect other resources without your knowledge. A breach in your pipeline could lead to a catastrophic failure across your entire cloud infrastructure.

The only takeaway from this section would be this: your home-brewed RBAC system should be fine-grained enough so that users relying on your product can apply this principle. If your permission model only supports coarse-grained roles like "Admin" and "User", you're forcing your customers into a security risk.

Final Thoughts

Designing an RBAC system is a classic exercise in balancing flexibility, performance, and security. The schema outlined here is a battle-tested starting point for most SaaS applications. It separates concerns, allows for complex organizational structures, and provides the granularity needed for the Principle of Least Privilege. The key is to start with a clear understanding of your entities and their relationships, and then make deliberate trade-offs based on your specific scalability and security requirements.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion