A data-driven look at the common advice that savings accounts are a losing proposition against inflation, examining historical trends, current rates, and the nuances that get lost in oversimplified financial advice.

The UK Personal Finance subreddit is a fascinating window into collective financial anxiety. Amidst the budgeting tips and pension confusion, a consistent drumbeat emerges: "Sticking money in a savings account will see it eaten away by inflation." This advice is delivered with the certainty of a physical law, a foregone conclusion that saving in cash is a fool's errand. But is this universally true, or is it a simplification that ignores historical context and current realities?

The Mechanics of Erosion

At its core, the argument is mathematically sound. Inflation represents the general rise in prices, meaning your money's purchasing power diminishes over time. If a loaf of bread costs £1.50 today and rises to £1.60 next year, your £1.50 can no longer buy that loaf. Interest, conversely, is the reward for deferring consumption—banks pay you to hold your money with them.

The critical comparison is between the real interest rate (nominal interest minus inflation) and zero. If your savings account yields 3% interest but inflation runs at 4%, your real return is -1%. Your nominal balance grows, but what it can buy shrinks.

The Bank of England's current stance illustrates this tension. With a Bank Rate of 3.75% and inflation at 3.2% (target: 2%), the immediate picture suggests savings are slightly ahead. However, this snapshot is misleading. Interest rates are a current tool, while inflation reflects the past year's price changes. They are not perfectly synchronized metrics.

Historical Patterns: The 2008 Anomaly

To understand the long-term relationship, we need to look beyond the present. The UK publishes multiple inflation measures (CPI, RPI), and savings accounts offer wildly variable rates, often with introductory bonuses that evaporate. This complexity makes precise modeling difficult, but historical averages reveal a pattern.

Using the Bank of England's historical data, we can compare two periods:

1975 to 2023: £1,000 saved in 1975, with average interest compounded, grew to approximately £18,000. The same amount, adjusted for inflation, was worth about £7,300. Here, compound interest decisively outpaced inflation.

2008 to 2023: The story changes dramatically. £1,000 saved in 2008 grew to roughly £1,180. Inflation-adjusted, it needed to be £1,540 to maintain purchasing power. This represents a real loss of over £300.

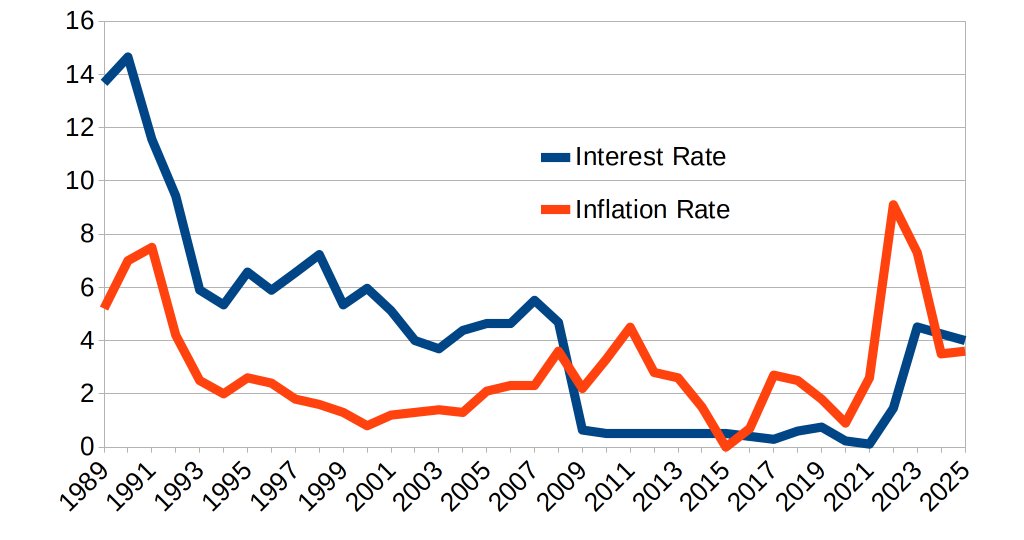

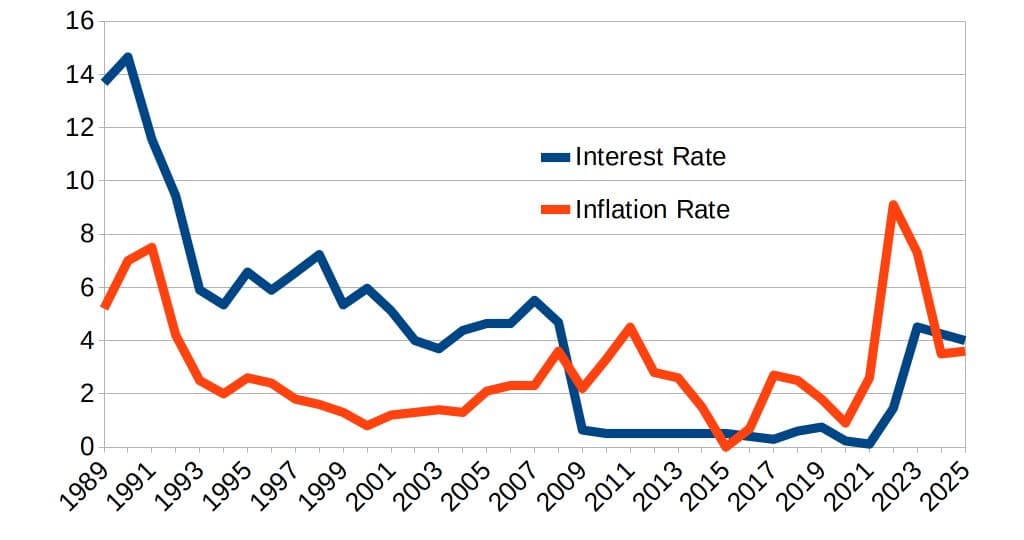

Plotting annual UK inflation and interest rates over the last 17 years reveals a stark trend: following the 2008 financial crisis, a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates (a response to the crisis and later quantitative easing) consistently failed to keep pace with inflation. This created a lost decade for cash savers, cementing the "savings lose to inflation" narrative in the public consciousness.

The Turning Point and Its Caveats

The graph shows this gap slowly closing. We may be entering a new phase where central bank policy rates, raised to combat post-pandemic inflation, could once again offer positive real returns. However, this is not guaranteed. Monetary policy is reactive, and inflation can be volatile.

This analysis introduces several critical caveats that are often omitted from blanket advice:

- Tax Efficiency: Some savings vehicles, like ISAs in the UK, are tax-free. A 5% interest rate in a taxable account is effectively lower after tax, while an ISA's yield is pure. This can significantly alter the real return calculation.

- Personal Circumstances: The "average" person doesn't exist. An individual's risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals are paramount. For someone saving for a house deposit in the next two years, the volatility of the stock market is a far greater threat than inflation eroding a cash savings account.

- The Role of Cash: Cash savings serve purposes beyond pure return. They provide liquidity, emergency funds, and psychological security. The opportunity cost of not investing in higher-return assets must be weighed against the need for accessible, stable capital.

Conclusion: Beyond the Binary

The blanket statement that savings accounts lose to inflation is a useful heuristic for a specific period in recent history, but it is not an immutable truth. It oversimplifies a complex relationship between interest rates, inflation, and individual financial strategy.

Historical data shows that over the very long term (decades), compounding interest has generally outpaced inflation. However, the post-2008 era created a powerful recency bias. The current environment, with interest rates rising to meet inflation, challenges that bias.

The real question isn't whether savings accounts always lose to inflation, but whether they are the right tool for a specific financial goal at a specific time. For short-term needs and emergency funds, they remain essential. For long-term wealth building, they are likely insufficient on their own. The most prudent approach is to move beyond simplistic narratives and assess your own timeline, risk tolerance, and the prevailing economic cycle.

Resources:

- Bank of England Inflation Calculator

- Historical Savings Calculator (Uses Bank of England data)

- Bank of England Bank Rate History

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion