MIT researchers have demonstrated a new photonic chip design that achieves cooling to 10 times below the standard laser cooling limit, addressing a critical scalability bottleneck for chip-based quantum computers.

Quantum computers promise to solve problems that would take classical supercomputers decades, but their practical utility depends on scaling to thousands of qubits. The MIT team's breakthrough centers on trapped-ion quantum computing, where individual charged atoms serve as quantum bits. While traditional trapped-ion systems rely on bulky external lasers and optics, chip-based approaches integrate both the ion trap and light sources on a single photonic chip. This integration is essential for scalability, but existing chip-based systems have been limited by inefficient cooling methods.

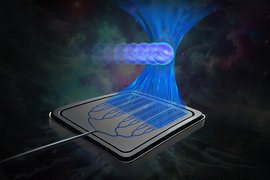

The core challenge is that quantum operations require ions to be cooled to near absolute zero—colder than even cryostats can achieve. Standard laser cooling techniques hit a fundamental limit called the Doppler limit, leaving residual vibrational energy that degrades computational accuracy. The MIT team's solution uses polarization-gradient cooling, a more complex technique that creates a rotating vortex of light by intersecting two beams with different polarizations. This vortex forces ions to stop vibrating more efficiently than conventional methods.

The innovation lies in implementing this technique on a photonic chip. The researchers designed a chip with two nanoscale antennas that emit precisely controlled light beams upward to manipulate ions trapped above the chip. These antennas are connected by waveguides that stabilize the optical routing, ensuring the light patterns remain stable. Each antenna features tiny curved notches spaced to maximize light delivery to the ion. This design achieves cooling 10 times below the Doppler limit in about 100 microseconds—several times faster than existing techniques.

"When we emit light from integrated antennas, it behaves differently than with bulk optics. The beams, and generated light patterns, become extremely stable," explains Ethan Clements, a former MIT postdoc now at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. "Having these stable patterns allows us to explore ion behaviors with significantly more control."

The research demonstrates a critical step toward scalable quantum architectures. Traditional trapped-ion systems require entire rooms of optical components to address just a few dozen ions. The integrated approach eliminates external optics, making it feasible to envision thousands of sites on a single chip working together. "Now, we can envision having thousands of sites on a single chip that all interface up to many ions, all working together in a scalable way," says Felix Knollmann, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Physics.

The team's work builds on years of development at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, where researchers have been designing gratings to emit diverse polarizations of light. The cross-institutional collaboration between MIT campus researchers and Lincoln Laboratory scientists proved crucial. "Key to achieving this advance was the cross-Institute collaboration between the MIT campus and Lincoln groups, a model that we can build on as we take these next steps," notes John Chiaverini, senior member of the technical staff at Lincoln Laboratory and a principal investigator in MIT's Center for Quantum Engineering.

Beyond cooling, the stable light patterns generated by this architecture open doors to other quantum operations. "By introducing polarization diversity to integrated-photonics-based trapped-ion systems, this work opens the door to a variety of advanced operations for trapped ions that weren't previously attainable, even beyond efficient ion cooling," says Jelena Notaros, the Robert J. Shillman Career Development Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT and senior author of the research.

The team's future work will include characterizing different chip architectures and demonstrating polarization-gradient cooling with multiple ions. They also plan to explore other applications that could benefit from the stable light beams this architecture can generate. The research appears in two joint publications in Light: Science and Applications and Physical Review Letters.

For more details on the research, see the papers: "Integrated-photonics-based systems for polarization-gradient cooling of trapped ions" and "Sub-Doppler Cooling of a Trapped Ion in a Phase-Stable Polarization Gradient". The work was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. National Science Foundation, MIT Center for Quantum Engineering, U.S. Department of Defense, and MIT fellowships.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion