Einstein's general relativity transformed time from a rigid constant into a dynamic dimension, bending under gravity's influence. This article unpacks how this warping slows time near massive objects like black holes and alters aging for astronauts on the ISS. Explore the profound implications for space travel, astrophysics, and our fundamental understanding of the universe.

For centuries, time was seen as an immutable river, flowing uniformly for all. That changed in 1915 when Albert Einstein unveiled his theory of general relativity, fusing space and time into a single, malleable fabric. "Einstein’s general theory of relativity requires that we can treat space and time as the same thing," explains Lia Medeiros, an astrophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. "My entire career started because I thought time slowing down was the craziest thing and I wanted to understand it." This revelation didn't just rewrite physics textbooks—it reshaped how we perceive reality, from Earth's surface to the edge of black holes.

The Fabric of the Universe: Space-Time Explained

Humans navigate a three-dimensional world, experiencing time as a separate, linear progression. But Einstein’s theory posits that time is a fourth dimension, intrinsically woven into the spatial fabric. Gravity, rather than a force, emerges as the curvature of this space-time continuum. "What we experience as gravity is actually the curvature of space-time," Medeiros emphasizes. This curvature means time dilates—slowing down near massive objects. Picture twins: one living in a skyscraper penthouse, the other in the basement. Due to Earth's gravity, the basement dweller ages marginally slower. On cosmic scales, this effect becomes staggering.

Relativity in Action: Astronauts, ISS, and the Speed-Time Paradox

Astronauts orbiting Earth experience time differently, but not for the reasons you might think. The International Space Station (ISS) sits farther from Earth’s gravitational pull, which should, in theory, speed up time slightly relative to the surface. Yet, astronauts return having aged less than those on Earth. Why? Velocity counteracts gravity's effect. At the ISS's high orbital speed (about 17,500 mph), time itself slows down. Calculations show a six-month ISS mission ages an astronaut ~0.005 seconds less than ground-based counterparts. This isn't sci-fi—it's measurable physics, crucial for precision technologies like GPS satellites, which must account for relativistic effects to avoid navigational errors.

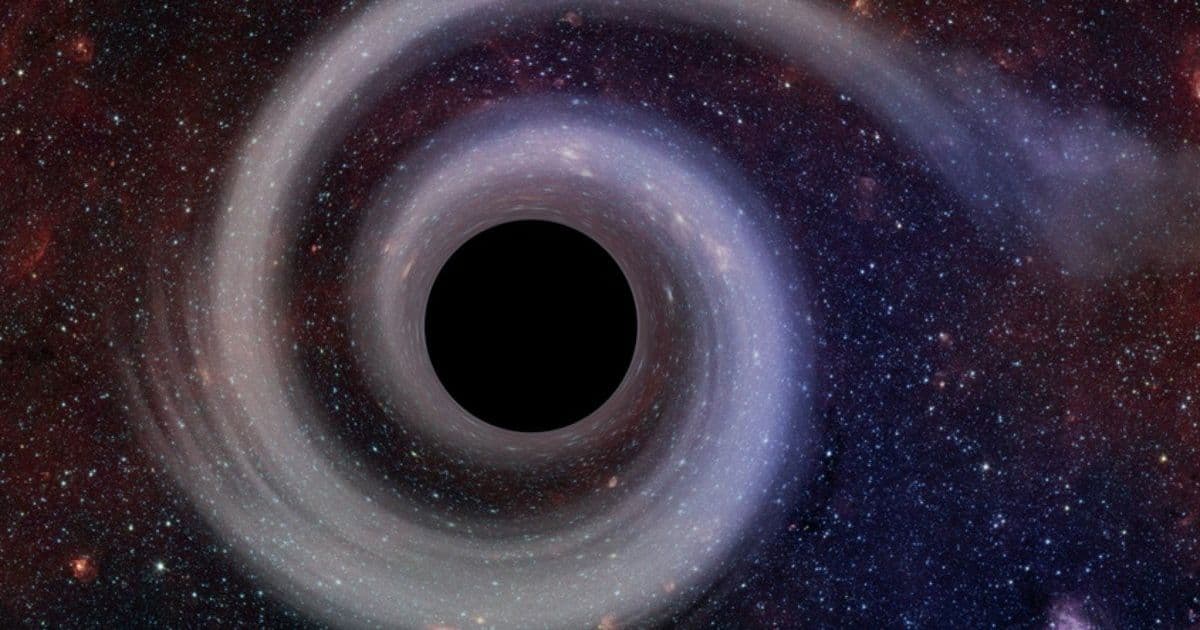

Extreme Warping: Black Holes and the Illusion of Frozen Time

The most dramatic time dilation occurs near black holes. At the event horizon—the point of no return—gravity’s curve becomes so intense that time grinds to a near halt for distant observers.  shows the eerie allure of these cosmic phenomena. "If you are watching me fall into a black hole, you’ll get really bored," Medeiros notes wryly. To an outsider, the infalling object appears frozen, though the traveler experiences a catastrophic end. Similarly, approaching light speed halts aging entirely; photons, traveling at light speed, don't age. These extremes aren't just theoretical—they challenge our notions of causality and inform research into quantum gravity.

shows the eerie allure of these cosmic phenomena. "If you are watching me fall into a black hole, you’ll get really bored," Medeiros notes wryly. To an outsider, the infalling object appears frozen, though the traveler experiences a catastrophic end. Similarly, approaching light speed halts aging entirely; photons, traveling at light speed, don't age. These extremes aren't just theoretical—they challenge our notions of causality and inform research into quantum gravity.

Why This Matters Beyond the Cosmos

Space-time curvature isn't abstract philosophy; it's foundational to modern technology. GPS systems rely on correcting for time dilation between satellites and Earth, proving relativity daily in our smartphones. For future Mars missions, engineers must model time differentials to synchronize communications and operations. Meanwhile, astrophysicists use these principles to study gravitational waves, revealing collisions of black holes billions of light-years away. As we push into deep space, understanding relativistic time becomes essential for human survival and exploration.

Einstein’s vision of a unified space-time continuum continues to unravel universe mysteries, reminding us that time is not a backdrop but a player in cosmic drama. Every second we measure is a local phenomenon, bending to the whims of gravity and motion—a humbling testament to physics' power to redefine reality.

Source: Discover Magazine, authored by Joshua Rapp Learn, with contributions from astrophysicist Lia Medeiros. Peer-reviewed studies include research from Nature on time perception in astronauts.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion