Rob Bowley examines why successive GenAI model improvements don't feel transformative, arguing that the technology operates within a fundamentally constrained interface that compresses reality into lossy digital representations, making it more like faster horses than trains—a tool that optimizes within existing systems rather than breaking their fundamental constraints.

The steady march of GenAI model improvements has left me with a peculiar sense of dissonance. While others react with genuine excitement to each new release, I find myself feeling that successive advances don't particularly change my experience, even though I use these tools constantly and have done since ChatGPT-4's release nearly three years ago. I couldn't imagine a world without them now—they already feel as transformative as the web. Yet the magic seems to fade with each upgrade, and I've come to believe this isn't just habituation but points to deeper structural reasons why the experience has plateaued, at least for me.

The Lossy Interface Problem

All meaningful work begins in a physical, social, constraint-filled environment. We reason with space, time, bodies, artifacts, relationships, incentives, and history. Much of this understanding is tacit—we sense it before we can explain it. To involve a computer, this reality must be translated into symbols: text, files, data models, diagrams, prompts. Every translation step compresses context and throws information away. There is loss from brain to keyboard, loss from keyboard to prompt, and loss again when output returns and must be interpreted.

GenAI only ever sees what makes it across that boundary. It reasons over compressed representations of reality that humans have already filtered, simplified, and distorted. Better models reduce friction within that interface, but they don't change its dimensionality. In that respect, it doesn't really matter how "smart" the models get, or how well they perform on the latest benchmarks. The boundary stays the same.

Because of this, GenAI works best where the world is already well-represented in digital form. As soon as outcomes depend on things outside its boundary, usefulness drops sharply. This is why GenAI helps with slices of work, not whole systems. It's powerful but fundamentally bounded.

Consider real-world examples. In software development, generating code hasn't been the main bottleneck since we moved away from punch cards. The far bigger constraints are understanding problems, communicating with stakeholders, working effectively with other people, designing systems, managing risks and trade-offs, and operating systems in complex social environments over time. In healthcare, GenAI can assist with diagnosis or documentation, but outcomes are dominated by staff, facilities, funding, and coordination across complex human systems. Better reasoning does not create more nurses or hospital beds.

In both cases, GenAI accelerates parts of work without shifting the underlying constraint.

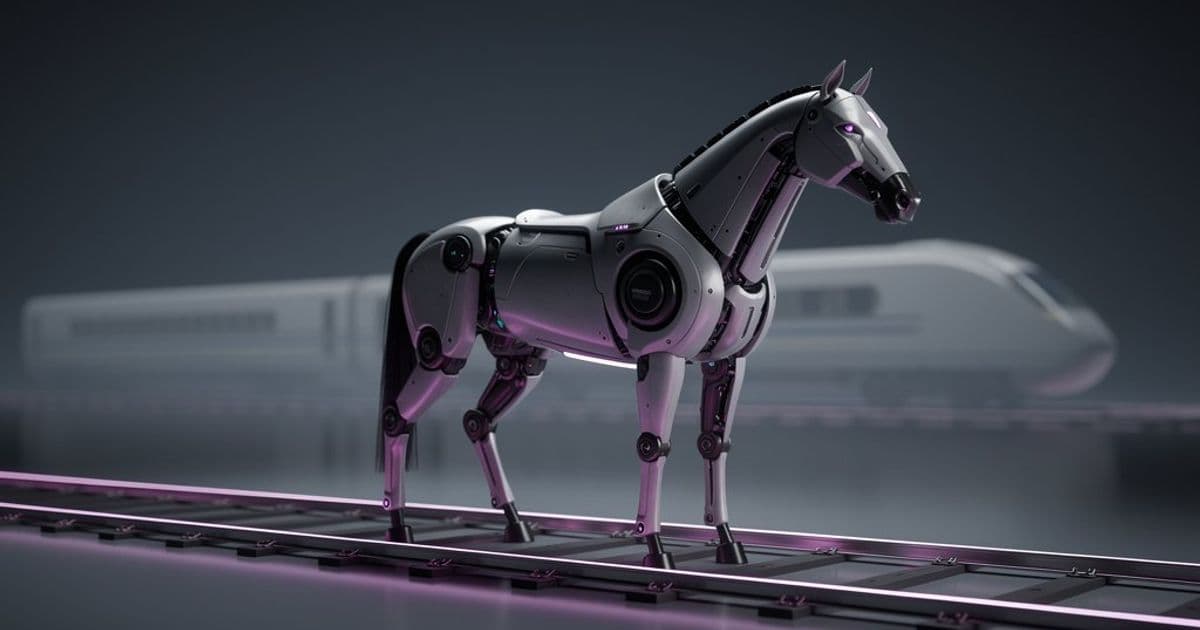

Faster Horses, Not Trains

This leads to a crucial distinction. GenAI feels like faster horses rather than trains. It makes us more effective at things we were already doing—writing, code, analysis, planning, sense-making—but operates on only parts, thin slices of systems. Trains didn't just make transport faster; they removed a hard upper bound on the movement of people and goods. Once that constraint moved, everything else reorganized around it: supply chains, labour markets, cities, timekeeping, and even how people understood distance and work. Railways weren't just tools inside the system—they became the system.

GenAI doesn't yet do that. It works through a narrow, virtual interface and plugs into existing workflows. But as often as not, the real systematic constraints lie elsewhere.

What Actually Changed the World

A recent conversation reminded me of Vaclav Smil's How the World Really Works, which I read last year. Smil highlights that modern civilization rests on a small number of physical pillars: energy, food production (especially nitrogen), materials like steel and cement, and transport. Changes in these pillars led to the biggest transformations in human life. Information technology barely registers at that level in his analysis. He doesn't deny its importance but treats it as secondary, an optimizer of systems whose limits are set elsewhere.

Through that lens, GenAI doesn't yet register as a civilization-shaping force. It doesn't produce energy, grow food, create new materials, or move mass. It operates almost entirely above those pillars, improving coordination, design, and decision-making around systems whose hard limits are set elsewhere.

That doesn't make it trivial, but it explains why, so far, it looks closer to previous waves of information technology than to steam or electricity. It optimizes within existing constraints rather than breaking them.

The Big If

Smil's framing doesn't say GenAI cannot matter at an industrial scale. It says where it would have to show up. GenAI becomes civilization-shaping only if it materially accelerates breakthroughs in those physical pillars—things that change what the world can physically sustain. This is where "superintelligence" comes in. If GenAI can explore hypothesis spaces humans cannot, design and run experiments, or compress decades of scientific iteration into years, resulting in major scientific breakthroughs, it moves from optimizing within constraints to changing them.

This is also where my own doubts sit. Many think just scaling what we have now will get us there. For those who don't believe that but are still optimistic about AI's potential, they turn to world models, embodiment, or agents that can act in the real world. There are sketches and hopes for how this may happen, but as yet, not much more than that.

So while superintelligence is the path by which AI could plausibly become industrial-scale transformative, it's a long and uncertain one.

What Kind of Change Are We Talking About?

If you mean web-scale change, then GenAI is already there. But if we mean the kind of change associated with the industrial revolution—longer lives, better health, radically different working conditions, step changes in material living standards—then what we have today does not qualify. Historically, those shifts followed from breaking physical constraints, not from better information or reasoning alone.

For me, and why I'm not really feeling successive model improvements, it isn't that GenAI lacks value. It's that those improvements don't change the shape of what's possible. They operate within the same narrow, lossy interface, so they barely register in practical terms. GenAI still adds value, and already feels web-scale transformative. But until that boundary moves, or something else breaks the underlying constraints, they don't feel like steps toward an industrial-revolution-scale shift.

The trajectory suggests we're optimizing within a bounded system rather than expanding the system itself. Each model improvement makes the horse faster, but we're still riding through the same terrain, constrained by the same physical and social realities that existed before. The real question isn't whether GenAI will continue to improve—it almost certainly will—but whether those improvements will ever be sufficient to break through the interface boundary and reshape the fundamental constraints of our world.

Until then, we're building faster horses while dreaming of trains.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion