A technical author discovers a publisher flooding the market with 800+ AI-generated books on niche programming topics, revealing how industrial-scale content spam threatens to drown out genuine technical knowledge.

The discovery began with a book about Starlark, a Python-derived language I managed at Google. Finding a newly published 100-page volume on this niche topic should have been flattering, but instead it triggered immediate suspicion. Starlark is too specialized to warrant a full book, yet there it was: professionally designed, available across multiple retailers, with a description that seemed legitimate. The author was listed as William Smith, published by HiTeX Press.

What made this unsettling was the book's surface-level credibility. It explained language goals and history, contained references I recognized from my own writing, and appeared to follow a logical structure. Yet something felt fundamentally wrong. When I asked Gemini about it, the AI suggested it was "almost certainly a low-quality, possibly AI-generated, product" - an assessment that carried its own irony, as my friend pointed out, given that an LLM was questioning another LLM's authorship.

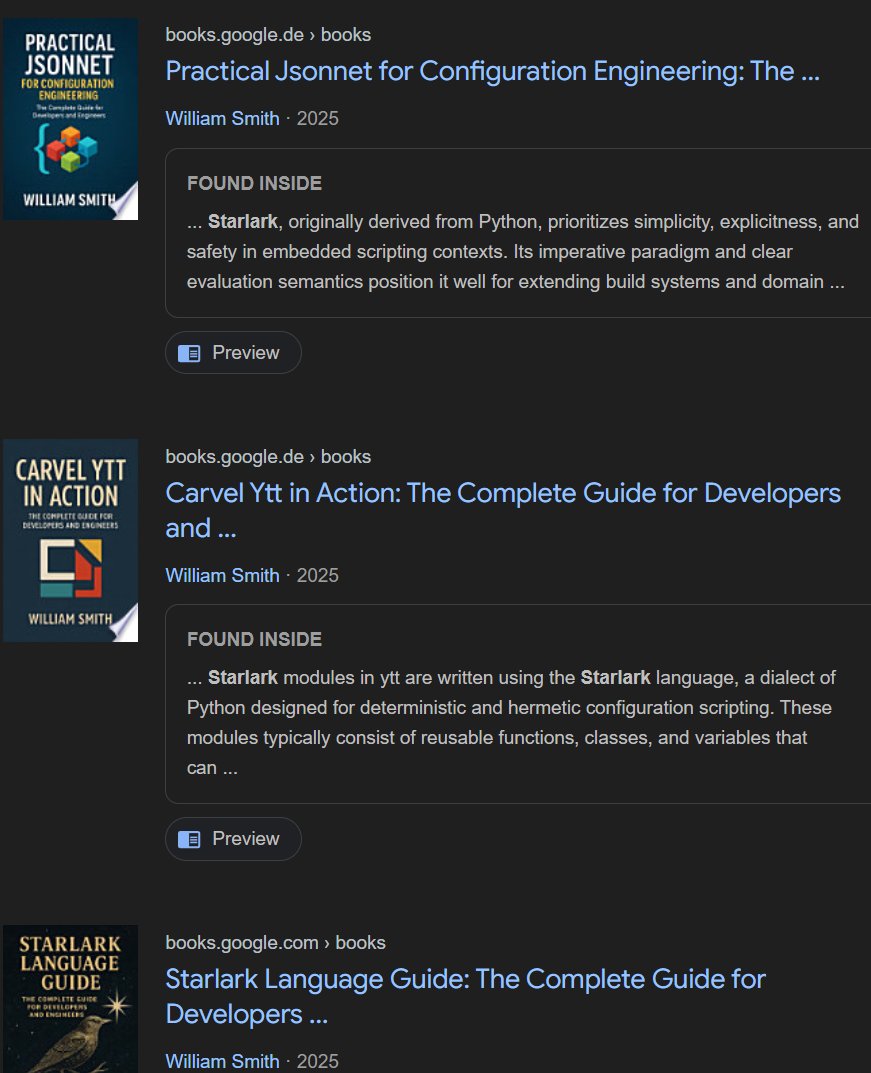

Digging deeper revealed the scale of the operation. Searching for "Starlark" on Google Books surfaced similar suspicious titles: "Practical Jsonnet for Configuration Engineering" and "Carvel Ytt in Action - The Complete Guide for Developers and Engineers." All three shared the same author and publication year. This seemed improbable - who would dedicate time to writing comprehensive guides on these obscure tools?

The answer became clear through Overdrive, where HiTeX Press's catalog revealed over 800 technical books published within a single year, authored by just two people: William Smith and Richard Johnson. The topics spanned the entire landscape of software development, as if someone had fed a list of GitHub project names into an automated system and generated a book for each. At this volume, human authorship becomes mathematically impossible - no one could even read that much content, let alone write and edit it.

The critical question was quality. Could AI actually produce useful technical content? I examined the Starlark book's free preview, expecting to find either surprisingly competent writing or obvious filler. What I found was worse: confident hallucination.

Starlark has three official interpreters - Java, Go, and Rust implementations. The book's code samples referenced a C++ implementation that doesn't exist. The API calls were complete fabrications. This wasn't just poor quality; it was actively misleading. A developer following these examples would waste hours debugging code that could never work.

The table of contents revealed deeper problems. It listed sections covering features that don't exist in Starlark, and the overall structure lacked any coherent purpose. The book read like a random collection of facts, some accurate, some invented, with no guiding use-case or pedagogical strategy. It wasn't written to teach or inform; it was generated to fill a catalog slot.

This represents a fundamental shift in how technical content spam operates. Traditional spam was obvious - poorly written, badly formatted, easy to filter. AI-generated spam can mimic the surface characteristics of legitimate work: proper structure, confident tone, professional formatting. The deception only becomes apparent when you possess enough domain expertise to spot the hallucinations.

HiTeX Press has created an industrial spam factory, but the implications extend beyond one publisher. Amazon and other retailers are flooded with these books, priced around €8 each. The immediate harm is financial - readers paying for garbage. But the deeper damage is informational: the pollution of search results, the erosion of trust in digital bookstores, and the time cost of filtering signal from noise.

For newcomers to a technology, the risk is particularly acute. A beginner learning Go might encounter HiTeX's "Go programming language reference" and trust its description as an "authoritative guide." They wouldn't know to question why "error handling" is listed as an advanced chapter, or why basic language features like "tokens" and "operators" are presented as special topics. By the time they realize the book is useless, they've wasted both money and time.

The counter-argument is that AI assistance in writing isn't inherently bad. Many authors use LLMs for editing, brainstorming, or drafting. The distinction lies in intent and oversight. A human author using AI as a tool maintains responsibility for accuracy and pedagogical value. HiTeX Press inverts this relationship entirely - the AI generates, and no human verifies.

This creates an asymmetry that traditional publishing never faced. A single bad human author can produce a flawed book; a bad publisher might release a few poor titles. But an AI system can generate hundreds of books simultaneously, each potentially containing subtle errors that require expert knowledge to detect. The scale of potential misinformation dwarfs previous concerns about quality control.

Book stores face a difficult challenge. Automated filtering can't easily distinguish between AI-generated spam and legitimate niche technical books. Manual review becomes impossible at the volume HiTeX is producing. The result is a market where quality signals break down, and readers must become their own publishers' detectives.

The Starlark book I discovered serves as a warning. It looks like a real book, reads like a real book, but contains information that could derail a developer's work. HiTeX Press isn't publishing books; it's publishing spam designed to capture search traffic and exploit the trust readers place in published works. Until retailers and platforms develop effective countermeasures, the burden falls on readers to maintain skepticism, verify sources, and recognize that publication alone no longer implies human authorship or quality.

The problem will only intensify as AI capabilities improve. The solution requires not just better detection tools, but a fundamental rethinking of how we validate and curate technical knowledge in an age where content generation has become trivial, but verification remains expensive and necessary.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion