The untold story of how a Stanford research project called Disco proved that x86 processors could support virtualization, paving the way for VMware to create an industry that now powers the entire cloud economy.

Is there a technology that is more taken for granted in modern computing than virtualization? It's an essential part of so many parts of modern computing, including cloud infrastructure. One could draw a straight line between virtual machines, which found their footing on x86 at the turn of the 21st century, and the myriad server farms that pepper the landscape today. But it wasn't a guarantee that this would ever happen. Intel had all but written off this concept from the server world—and seemed primed to move to a new generation of hardware that might have gotten them there. But a startup not only proved that virtualization was possible, but likely opened up a cloud-forward economy that didn't previously exist.

The Mainframe Roots of Virtualization

The concept of splitting a computer into multiple isolated parts traces back to IBM's mainframe era. In the 1970s, IBM coined the term "hypervisor"—essentially a "virtual machine monitor"—to describe software that could manage multiple virtual machines on a single physical system. The name itself was straightforward: it acted as a supervisor above the operating system supervisor.

A 1971 article by IBM employee Gary Allred explained the Hypervisor concept: it consisted of an addendum to an emulator program and a hardware modification on a Model 65 with a compatibility feature. The hardware modification divided the Model 65 into two partitions, each addressable from 0-n. The program addendum, having overlaid the system Program Status Words (PSW) with its own, became the interrupt handler for the entire system. After determining which partition had initiated the event causing the interrupt, control was transferred accordingly.

However, this approach had significant limitations. The Hypervisor required dedicated I/O devices for each partition, making the I/O configurations quite large and prohibitive for most users. Unlike modern virtual machines, it effectively ran two completely separated machines as if they weren't connected.

The Popek-Goldberg Theorems and the x86 Problem

In 1974, UCLA's Gerald Popek and Honeywell's Robert Goldberg developed three theorems that established the conditions for virtualization. Their Communications of the ACM piece proved to be something of a Moore's Law for virtualization in the decades afterward—a dividing line to prove what was possible.

The first theorem stated: "For any conventional third generation computer, a virtual machine monitor may be constructed if the set of sensitive instructions for that computer is a subset of the set of privileged instructions."

The x86 line of processors, with its CISC nature, violated many of these basic tenets. Intel had designed the x86 chipset to run software with different levels of privilege, set up in a series of "rings," with the goal of limiting the attack surface of the kernel. While this was good for security, it created problems for virtualization. The structure limited access to commands software could have, making it impossible to virtualize in the same way IBM had virtualized the System/360.

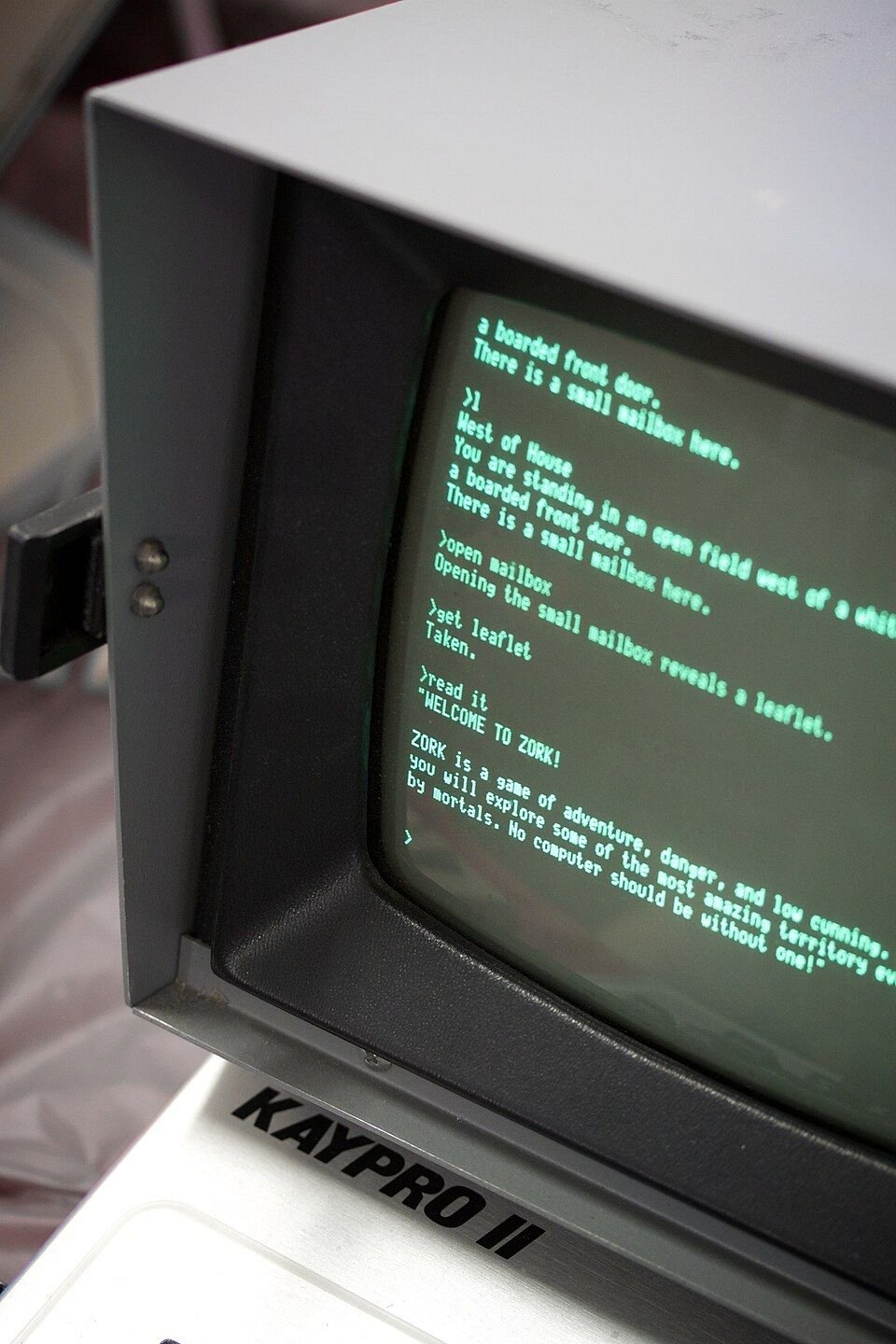

The x86 processor set violated the Popek-Goldberg theorems in more than a dozen distinct ways. This seemed to make VMs infeasible with the infrastructure the world currently worked on. Sure, it was technically possible to emulate a Linux machine on a Windows 2000 machine, but that introduced significant overhead—you were recreating hardware in software, likely the very same hardware the system already had.

Emerging Techniques: Dynamic Recompilation and JIT

There were hints that solutions might exist. On the Mac side, Apple pulled off something of a magic trick during its transition from 68000 to PowerPC by creating a translation layer that ran old code natively. Initially using emulation, Apple later switched to dynamic recompilation, a technique developed by Apple employee Eric Traut.

The system reprogrammed vintage MacOS code in real time. It was so effective that even in later PowerPC versions of the classic MacOS, much of the software was emulated 68k code that never needed updating because it just worked.

Meanwhile, Java popularized just-in-time compilation (JIT), making it possible for programs to execute on machines in real time without being tethered to specific architectures. JIT proved it was possible to translate applications in real time, but translating entire operating systems seemed beyond reach.

The Disco Project: Stanford's Breakthrough

The breakthrough came from an unexpected place: a computer science experiment run on a top-of-the-line SGI Origin 2000 server at Stanford University. Built by PhD students Edouard Bugnion and Scott Devine, with faculty advisor Mendel Rosenblum, Disco was an attempt to solve the challenges preventing virtual machines from reaching their full potential.

In their 1997 paper "Disco: Running Commodity Operating Systems on Scalable Multiprocessors," the team described how Disco could share resources between virtual machines. From the paper:

"Disco contains many features that reduce or eliminate the problems associated with traditional virtual machine monitors. Specifically, it minimizes the overhead of virtual machines and enhances the resource sharing between virtual machines running on the same system. Disco allows the operating systems running on different virtual machines to be coupled using standard distributed systems protocols such as NFS and TCP/IP. It also allows for efficient sharing of memory and disk resources between virtual machines."

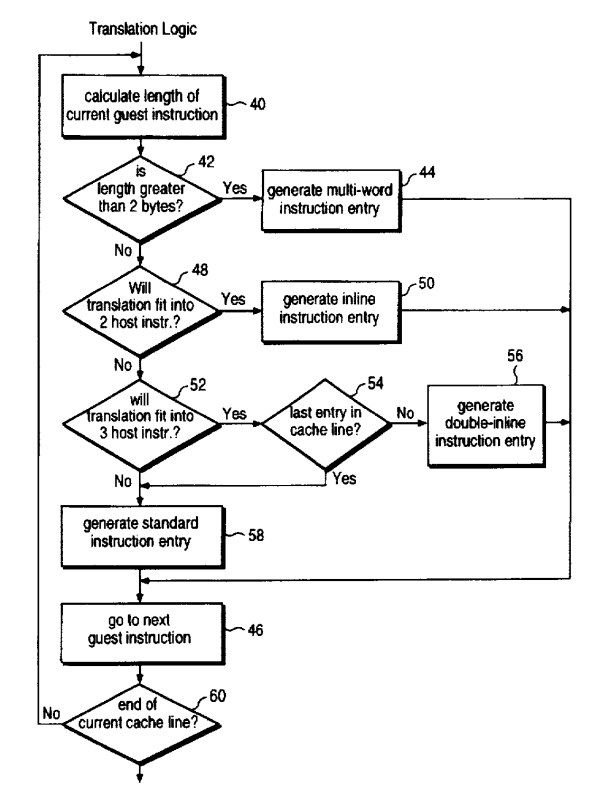

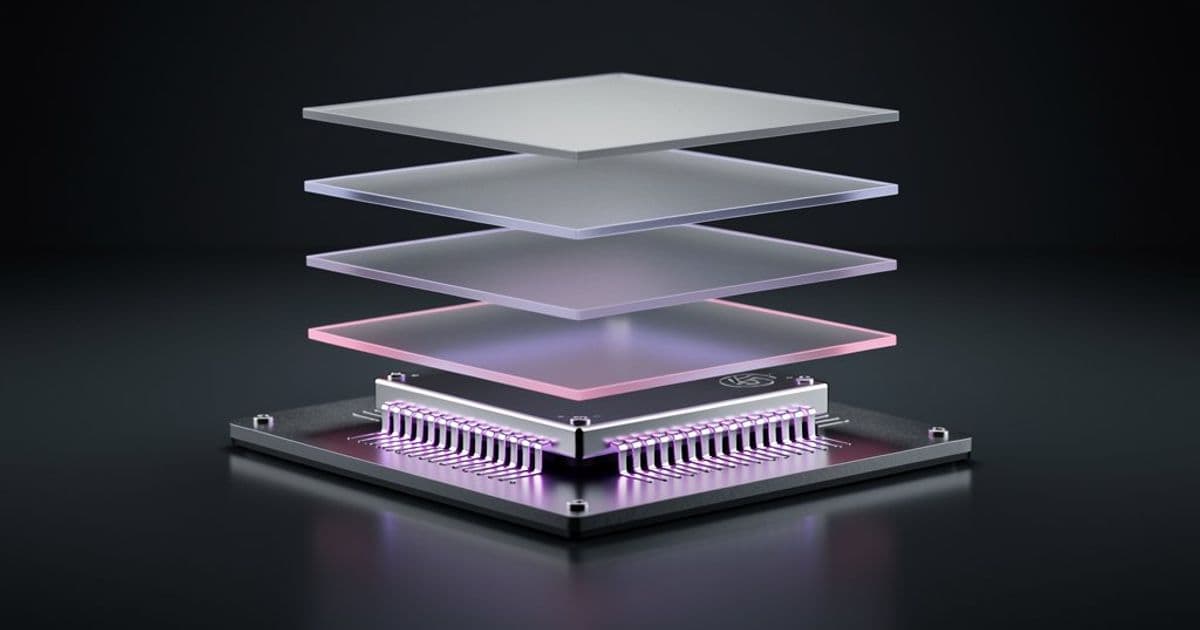

This was a fundamental shift from the System/360 approach requiring dedicated hardware. Disco proved that using a hypervisor in combination with just-in-time compilation caused only a very small performance decline. This discovery was arguably the basis of VMware's entire business.

The project was rooted in Rosenblum's work on SimOS, a prior initiative built on IRIX to experiment with completely simulating a computing environment through software alone. The SGI Origin 2000, one of the few systems that could handle multi-core processing, provided the headroom needed for extreme testing.

VMware Workstation: From Research to Product

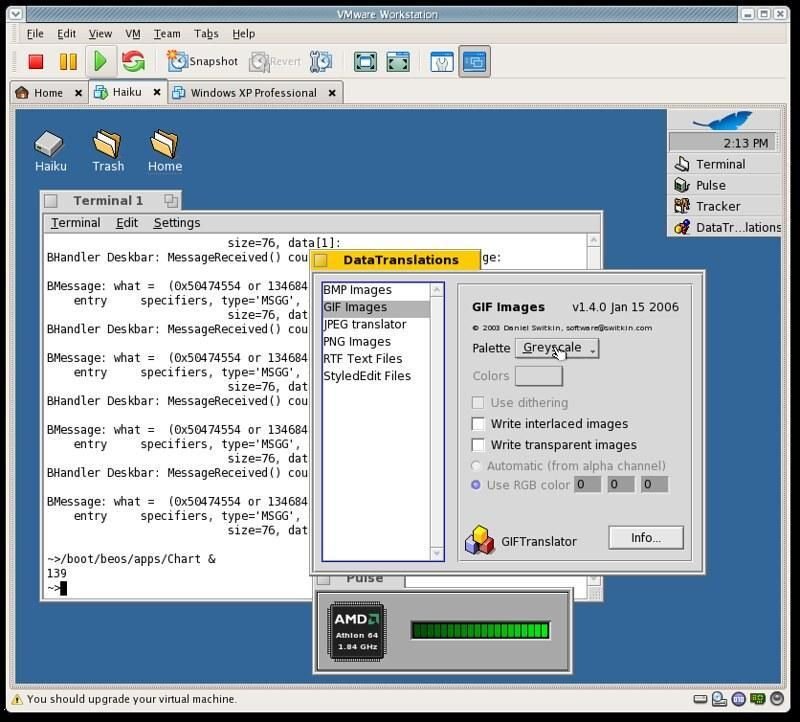

Within a year of Disco's creation, Bugnion, Devine, and Rosenblum became three co-founders of VMware. Rosenblum's wife Diane Greene, an engineer who had worked at SGI, became the fourth. Just two years after the paper's release, VMware hit the ground running. After a year in stealth mode, VMware Workstation—a Disco adaptation for Windows and Linux—made a huge splash at the start of 1999.

The founders faced significant challenges. The x86's convoluted instruction set and diverse peripheral ecosystem created added complexities. They had to implement support for operating systems one at a time. Linux was easy. Windows was hard. OS/2 was impossible.

As they later wrote: "Although our VMM did not depend on any internal semantics or interfaces of its guest operating systems, it depended heavily on understanding the ways they configured the hardware. Case-in-point: we considered supporting OS/2, a legacy operating system from IBM. However, OS/2 made extensive use of many features of the x86 architecture that we never encountered with other guest operating systems. Furthermore, the way in which these features were used made it particularly hard to virtualize. Ultimately, although we invested a significant amount of time in OS/2-specific optimizations, we ended up abandoning the effort."

All that work to develop hardware drivers and manage edge cases—and even create some fake virtual hardware that only existed in software—paid off. The self-funded company quickly found itself making $5 million in a matter of months.

The Monks and the Mainstream

In a 1999 USA Today profile, CEO Diane Greene noted that the company was getting email from Buddhist monks in Thailand who were fighting over whether to run Linux or Windows on their computers. VMware allowed them to split the difference.

"When we first put together the business plan for VMware in 1998, we never thought Buddhist monks in Thailand would be part of our customer base," Greene told the newspaper. "But it's certainly intriguing to be this global."

Monks were only the beginning. VMs proved highly usable in thousands of ways, as mechanisms for security and maintenance. Within a decade, Greene and Rosenblum had taken the company public, then sold it for more than $600 million. Two decades later, after a series of mergers and spinouts, it sold for a thousand times that amount.

The Ripple Effects

VMware's success had far-reaching consequences. The company had a multi-year head start to dominate virtualization. Intel and AMD didn't include native virtualization hardware on their chipsets until the mid-2000s. Microsoft had to acquire Connectix in 2003 to compete. Parallels didn't emerge until 2006, and open-source alternatives like Xen, QEMU, VirtualBox, and Proxmox didn't gain traction until the mid-2000s.

Perhaps VMware's most significant impact was on Intel's architecture strategy. Intel had spent billions developing Itanium, a new generation of chip on a different architecture. VMware essentially proved that with innovative hypervisors, you could work around x86's pain points for virtualization without breaking Intel's security model. If the existing x86 architecture was this capable, why switch?

Modern Legacy and Current State

The techniques pioneered by VMware now power the entire cloud economy. Amazon's EC2, launched in 2006, initially used the Xen hypervisor, which gained its superpowers thanks to virtualization hardware support added by Intel and AMD largely in response to VMware's success.

Virtualization has become essential for modernizing legacy embedded systems. It's now common in aircraft and industrial equipment where taking systems offline for updates isn't feasible. Diebold announced "the world's first virtualized ATM" in 2011, separating software from hardware to make updates easier.

However, VMware's story has taken a turn. In recent years, Broadcom acquired the company and aggressively reset its licensing model to maximize profitability, moving away from one-time licenses. As CIO Dive noted in 2024, this "seismic shift in enterprise IT" threatened to upend core infrastructure and disrupt critical business processes.

The founders left nearly two decades ago, and Dell's 2016 acquisition led to the entire Workstation team being fired. Recently, Broadcom began offering VMware Workstation—the program that started it all—for free, likely as a loss-leader in a market where virtualization options abound.

The Enduring Impact

VMware's $60 billion acquisition price reflects the inherent value of its original idea: we're better off with a few computers running many machines simultaneously than many computers running only a handful of tools.

The computing industry didn't anticipate that virtualization would simply raise demand for computers in general. The technology that was supposed to consolidate hardware instead enabled an explosion of new applications and services. Every modern cloud platform, container system, and development environment owes a debt to those Stanford researchers who proved that virtualization on x86 wasn't just possible—it was practical.

From Buddhist monks sharing computers to Fortune 500 companies modernizing aging hardware stacks, VMware's hypervisor solved a problem that Intel thought was unsolvable. In doing so, it didn't just create a company—it created the foundation for how we compute today.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion