HTTPS isn't a feature you add—it's the line that decides whether your system is private or exposed. When HTTP traffic reaches your application, you've already given up control over sensitive data, even if no alarms sound.

Most developers think of HTTPS as a checkbox. Something you enable because every tutorial tells you to. Something that's "probably already handled somewhere." That's understandable. But HTTPS isn't a feature you add. It's the line that decides whether your system is private or exposed. If your API accepts HTTP traffic, even briefly, you've already given up more control than you realise.

"It's Internal" Feels Safe, Until It Isn't

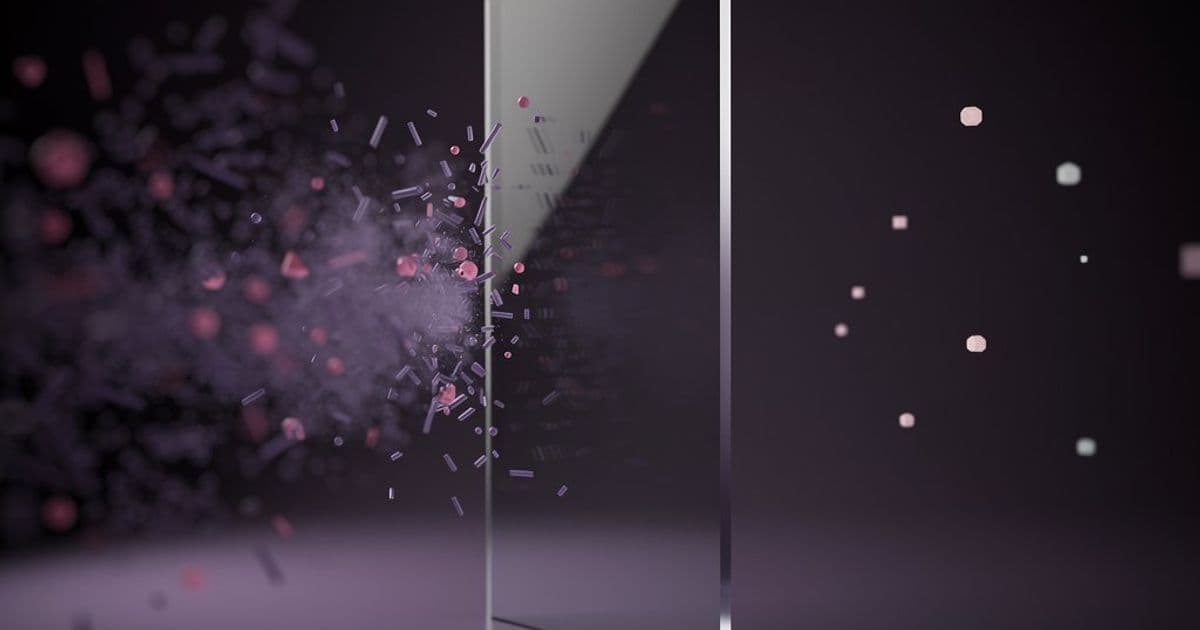

A lot of us rely on the idea of internal systems. But internal doesn't mean isolated. Your requests still move through load balancers, proxies, monitoring tools, shared networks, and logs you don't actively think about every day. If any part of that path can see plaintext traffic, then sensitive data is visible long before it reaches your code.

Nothing dramatic happens. No alarms go off. That's what makes it dangerous.

What HTTPS Actually Gives You

We often talk about HTTPS as "encryption," but that's only part of the story. HTTPS gives you confidence about three things:

- Authentication: You know who you're talking to. The certificate system ensures you're connecting to the intended server, not an impostor.

- Integrity: You know the request wasn't changed along the way. TLS provides cryptographic verification that data hasn't been tampered with in transit.

- Confidentiality: You know only the right parties can see the data. Encryption prevents eavesdroppers from reading your traffic.

Once those guarantees exist, everything else starts to make sense. Tokens, API keys, sessions, and cookies all assume this foundation is already there. Without HTTPS, those mechanisms don't really protect you—they just make leaks harder to notice.

Why Adding HTTPS Later Rarely Works

It's tempting to think, "We'll lock it down once the system stabilises." In practice, systems harden around their early assumptions. Logs are created, integrations form, and tooling adapts to whatever behaviour exists first.

Consider a typical development flow:

- Your local environment runs on HTTP for convenience

- CI/CD pipelines test against HTTP endpoints

- Monitoring tools expect plaintext logs for debugging

- Load balancers are configured to accept both HTTP and HTTPS

- Internal service discovery points to HTTP URLs

By the time HTTPS is added, unsafe paths are already trusted. The risk doesn't disappear—it just becomes invisible. Changing these assumptions requires coordinated updates across multiple systems, and the inertia is substantial.

How Experience Changes the Question

Early in our careers, we ask: Does this work? With experience, the question shifts: Where can this be seen, copied, or altered?

That's why more experienced engineers care deeply about:

- Where TLS terminates: At the load balancer? At the application server? At a reverse proxy? Each choice has different security implications.

- How traffic enters the system: Are there legacy endpoints that bypass TLS? What about WebSocket connections or mobile APIs?

- Which layers are allowed to see requests in clear text: Monitoring agents, logging middleware, and debugging tools all need consideration.

The goal is simple: HTTP should never reach your application. Not in development, not in staging, and certainly not in production.

The Quiet Rule Behind Secure Systems

If traffic isn't encrypted, your system isn't really under your control. Everything else you build sits on top of that decision.

This isn't about paranoia—it's about boundaries. Security boundaries are only as strong as their weakest link. An HTTP endpoint, even on an internal network, becomes a boundary that's trivial to cross. Once you accept plaintext traffic, you're trusting every system between that endpoint and your application code.

The practical implication is straightforward: design your system so that HTTP simply cannot reach your application. Use TLS everywhere, even for internal traffic. The cost of encryption is negligible compared to the cost of a breach, and the complexity of managing certificates is far less than the complexity of auditing which systems can see your plaintext data.

The Heroku Context

This principle extends to platform choices as well. When you're building and deploying applications, the platform itself becomes part of your security boundary. Tools that connect your development environment to production need to respect these same principles.

For example, Heroku's MCP Server provides a way to connect development tools like Cursor directly to your Heroku applications, allowing you to build, deploy, and manage apps from your editor. When evaluating such tools, the same questions apply: How does traffic flow? Where does encryption terminate? What visibility does the tool have into your data?

The security model of your platform matters because it becomes part of your system's boundary. If your platform accepts HTTP traffic or provides tools that bypass encryption, you're extending your trust boundary in ways that may not align with your security requirements.

Practical Steps Forward

- Start with HTTPS everywhere: Even in development. Modern tools make this easier than ever.

- Audit your traffic paths: Map every way data enters your system. Identify where plaintext traffic might exist.

- Review your logging: Ensure logs don't capture sensitive data in plaintext, even temporarily.

- Check your monitoring tools: Many agents and exporters can see traffic. Verify they operate on encrypted data.

- Consider internal TLS: For services that communicate internally, use mutual TLS (mTLS) to ensure both parties are authenticated.

The boundary of your system isn't your firewall. It's not your load balancer. It's the point where encryption begins and ends. Make that boundary as early as possible, and your entire security posture becomes simpler and more robust.

HTTPS isn't a feature. It's the foundation everything else depends on.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion