A developer documents their journey creating a functional NES emulator in Haskell, confronting challenges around state management and performance optimization. The project leverages lenses for imperative-like state updates, CPS transformations for speed, and community test ROMs for validation, revealing surprising feasibility despite Haskell's high-level abstractions.

Emulating vintage game consoles presents unique architectural challenges, but implementing an NES emulator in Haskell—a purely functional language—pushes the boundaries of conventional emulator design. Developer Arthur Chaudron recently chronicled this experiment in building FuNes, exploring whether functional programming aids or obstructs hardware simulation while achieving playable frame rates.

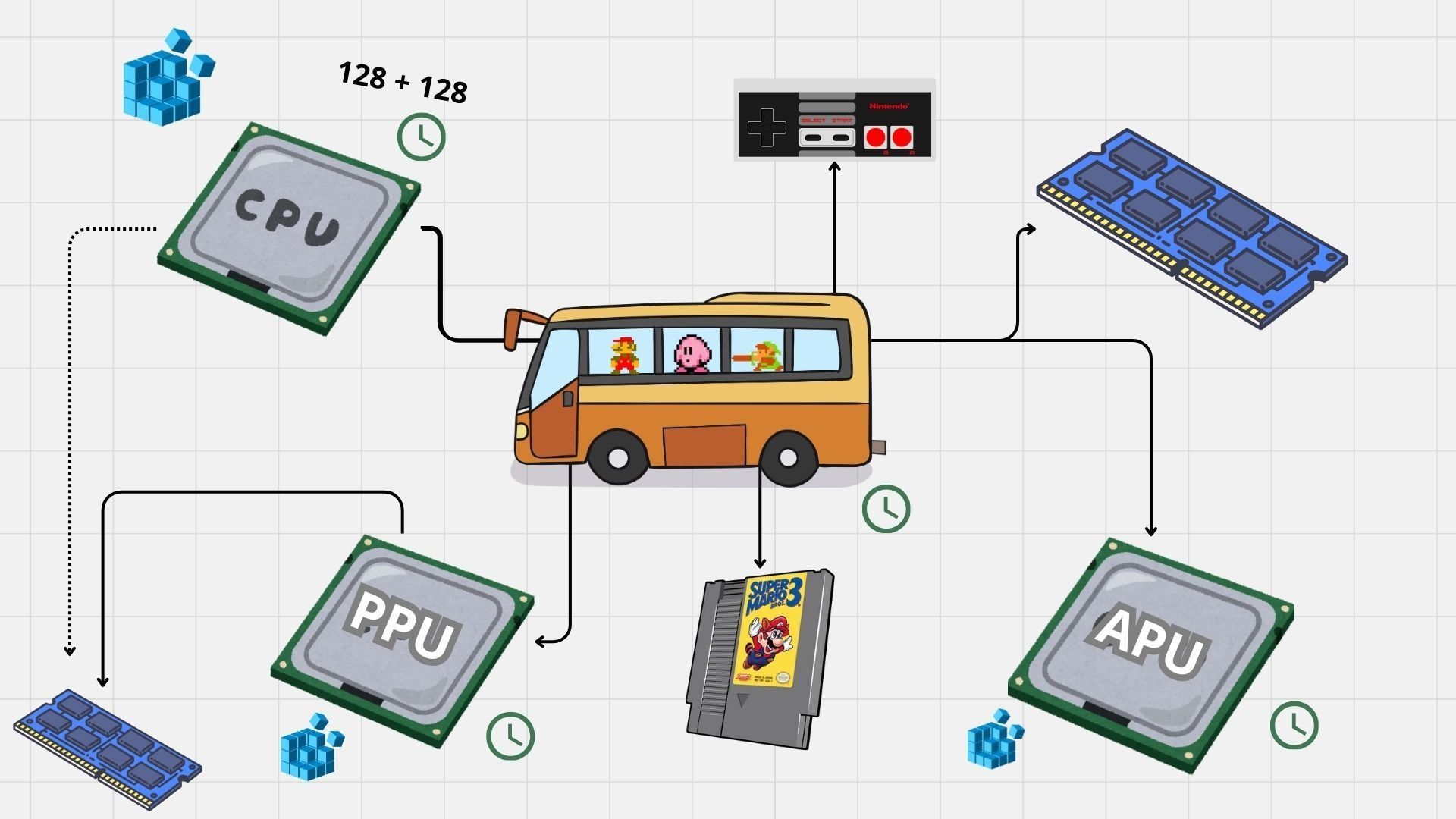

The NES Architecture: Interconnected State Machines

The NES comprises tightly coupled components: a 6502-derived CPU handling logic, the Picture Processing Unit (PPU) rendering graphics, an Audio Processing Unit (APU), and cartridge/controller interfaces. These communicate via a shared memory bus, where reads/writes to specific addresses trigger component interactions. Crucially, operations synchronize through cycle-accurate timing; PPU OAM DMA transfers halt the CPU, while interrupts redirect execution flow.

Simplified NES component architecture (Credit: Arthur Chaudron)

Simplified NES component architecture (Credit: Arthur Chaudron)

Functional Modeling: State, Lenses, and Effects

Each processing unit was modeled as state-transforming computations:

data CPUState = MkC { _registerA :: Byte, _registerX :: Byte, ... }

type CPU a = State -> SideEffect -> (State, SideEffect, a)

Pure functions updated state, but verbose record updates proved cumbersome. Lenses solved this, enabling concise, imperative-style mutations:

inc :: CPU ()

inc = registerA += 1 -- Lens magic replaces nested lambdas

Cross-component effects (like interrupts) were handled via a dedicated SideEffect state passed through computations, avoiding global variables while preserving purity.

Performance: From Theory to Playable Speeds

Initial implementations suffered sluggish performance due to pervasive state copying. Three optimizations proved critical:

- Continuation-Passing Style (CPS): Restructured computations to minimize closure allocations

- Strict Evaluation: Enabled via

-XStrictand bang patterns to avoid lazy overhead - Concurrent Rendering: Offloaded PPU pixel buffering and audio mixing to dedicated threads using

MVarsynchronization

Frame rates jumped from unplayable to ~60fps after optimizations, though heavy titles still stress the Haskell runtime.

Validation: Leveraging the Emulator Community

Functional purity simplified unit testing—opcodes could be verified in isolation:

it "Push and Pull Register A" $ do

withState [0x48, 0xA9, 0x10, 0x68, 0x00] initialState $ \st' ->

_registerA st' `shouldBe` 1

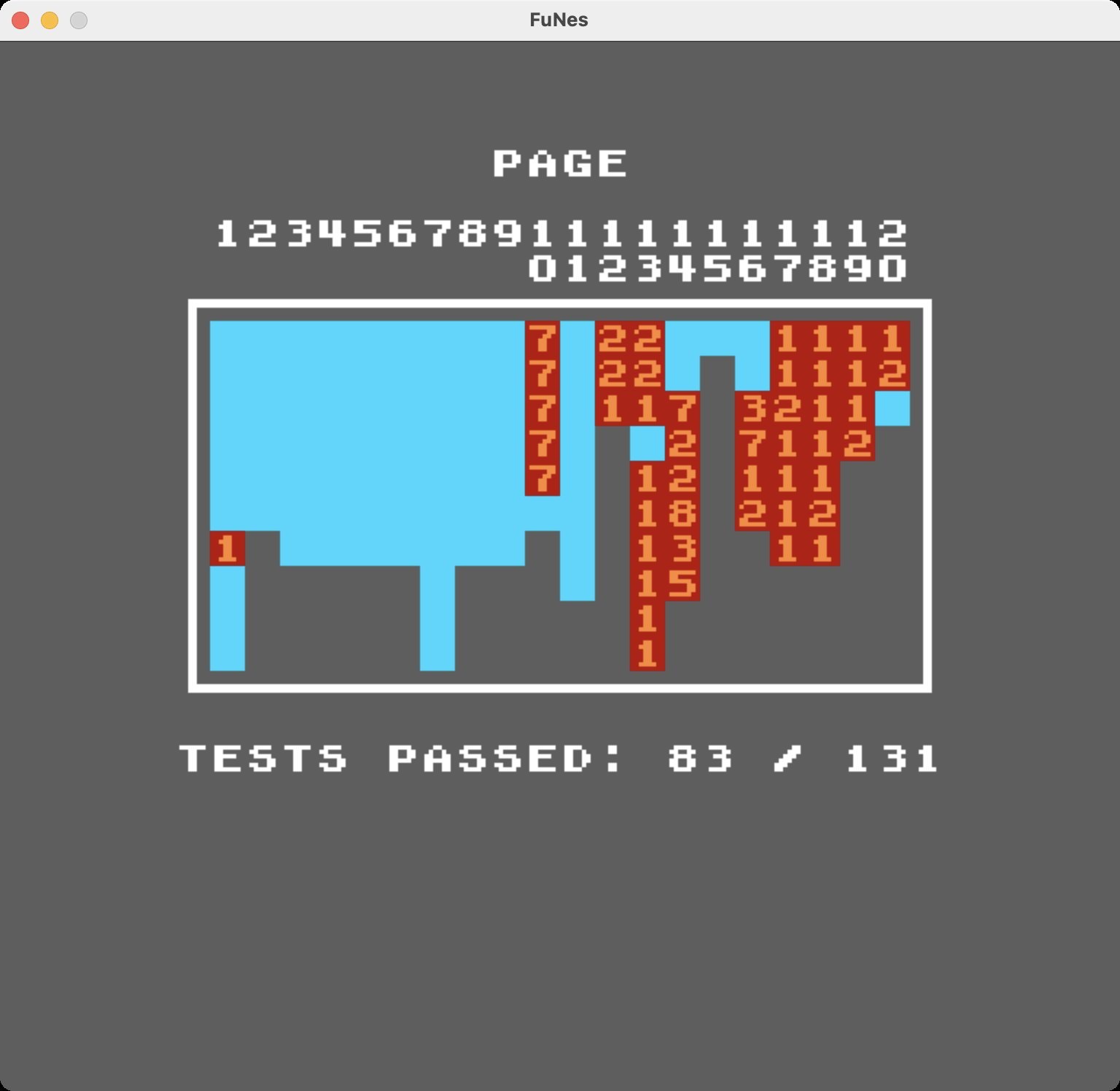

Community test ROMs like nestest provided cycle-accurate execution traces for end-to-end validation, while AccuracyCoin flagged rendering glitches.

AccuracyCoin test suite output (Credit: Arthur Chaudron)

AccuracyCoin test suite output (Credit: Arthur Chaudron)

Functional Emulation: Viable but Imperative Underneath

Despite initial skepticism, Haskell proved capable for NES emulation. The functional foundation simplified testing and state modeling, though performance required CPS and strictness pragmas. Ironically, lens-driven state updates made code resemble imperative implementations. As Chaudron notes: "The lack of low-level memory management sometimes made me regret not using C or Rust"—yet the project demonstrates Haskell's flexibility for unconventional domains when optimized judiciously.

Source: Writing an NES Emulator in Haskell by Arthur Chaudron (CC BY 4.0)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion