Despite alarming visualizations suggesting otherwise, the volume of space available in low Earth orbit is vast enough to accommodate current satellite populations with room to spare.

The visualization of satellites crowding Earth's orbit has become a popular way to illustrate the growing problem of space debris and collision risk. These animations, often showing thousands of dots swarming around our planet like angry bees, create a visceral impression of danger and overcrowding. But as with many visualizations, the reality is more nuanced than the imagery suggests.

When we look at the actual numbers, a different picture emerges. Low Earth orbit, the region extending from 160 to 2000 kilometers above Earth's surface, encompasses a staggering volume of space. To calculate this, we need to consider the spherical shell between these two altitudes. With Earth's radius at approximately 6400 kilometers, the LEO region spans from a radius of 6560 km to 8400 km.

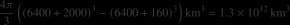

The volume of this spherical shell can be calculated using the formula for the volume of a sphere, subtracting the inner volume from the outer volume:

$$ \frac{4\pi}{3} \left((6400 + 2000)^3 - (6400 + 160)^3\right) \text{km}^3 = 1.3 \times 10^{12} ,\text{km}^3 $$

This enormous volume—1.3 trillion cubic kilometers—provides the context for understanding satellite distribution. With approximately 12,500 satellites currently operating in LEO, the average volume of space allocated to each satellite works out to about 100 million cubic kilometers.

To put this in perspective, imagine each satellite having a cube of space 464 kilometers on each side—that's roughly the distance from New York City to Washington, D.C. Even if we consider that satellites don't occupy perfect cubes and their orbits intersect, the sheer scale of available space is difficult to overstate.

This calculation, admittedly a "back-of-the-envelope" approach, serves as a crucial first word in the conversation about orbital congestion. It doesn't account for the complexities that make collision avoidance challenging: satellites following specific orbital planes, the concentration of objects in certain altitude bands, the presence of debris too small to track, or the fact that satellites in similar orbits move at similar velocities. These factors certainly increase collision risk beyond what simple volume calculations might suggest.

Yet the fundamental point remains: space is, by definition, mostly empty. The visual impression of crowding comes from representing satellites as discrete points in animations, where each point occupies no volume but is given equal visual weight. In reality, the average separation between objects is measured in hundreds of kilometers, not meters or centimeters.

The concern about orbital congestion is real and growing, particularly as companies like SpaceX, OneWeb, and Amazon plan to deploy tens of thousands of additional satellites in the coming years. The issue isn't that space is running out, but rather that orbital slots, frequency allocations, and the increasing risk of cascade collisions (where one collision creates debris that causes further collisions) present genuine challenges for space operations.

What this calculation reveals is that the problem isn't one of simple overcrowding but of orbital dynamics, debris management, and the need for international coordination. The solution lies not in abandoning LEO activities but in developing better tracking systems, establishing clear guidelines for satellite disposal, and creating frameworks for sharing this vast but finite resource.

The next time you see an animation of "crowded" space, remember the 100 million cubic kilometers per satellite. The challenge isn't that we're running out of room—it's that we're still learning how to responsibly share the room we have.

{{IMAGE:1}}

For those interested in exploring orbital mechanics and satellite distribution further, several resources provide deeper insights:

- The Union of Concerned Scientists Satellite Database maintains current counts and details of operational satellites

- NASA's Orbital Debris Program Office provides comprehensive information on space debris and mitigation strategies

- The European Space Agency's Space Debris Office offers regular assessments of the space environment

The mathematics of space may be simple, but the politics and engineering of sharing it are anything but. As we continue to expand our presence in orbit, understanding both the vastness of space and the real challenges of operating within it becomes increasingly important for the future of space exploration and utilization.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion