Before search engines and interactive documentation, Unix developers created a documentation standard so clear and structured that it remains the gold fifty years later. As AI tools struggle to parse today's fragmented documentation, these ancient man pages offer surprising insights into creating machine-friendly information architecture.

Before search engines and interactive documentation, Unix developers created a documentation standard so clear and structured that it remains the gold fifty years later. As AI tools struggle to parse today's fragmented documentation, these ancient man pages offer surprising insights into creating machine-friendly information architecture. This is the story of how 1970s documentation principles might hold the key to our AI-powered future.

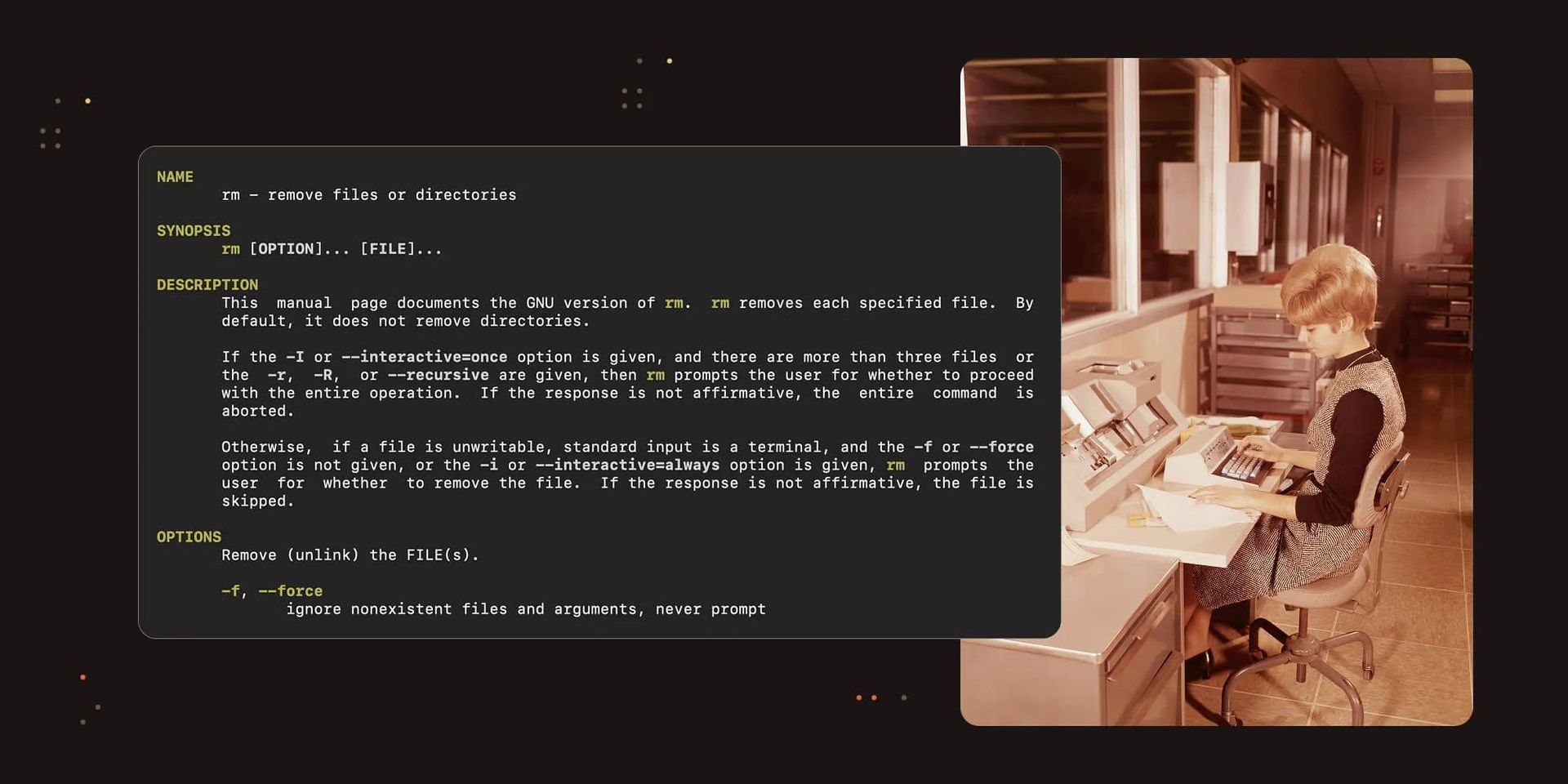

The Birth of Structured Documentation

In the early days of computing, documentation existed primarily in printed form or as oral tradition passed between mentors and apprentices. To look up a command argument or system function parameter, developers would physically navigate through binders, hoping the information was current before returning to their terminals to implement what they'd learned.

This cumbersome process prompted innovation in the early 1970s. One of the most notable examples was the Unix Programmer's Manual (1971), which covered administration of the new operating system and functions of the similarly new C programming language. Its sections followed a strict structure that would become remarkably influential:

- Name — The name of the command or function

- Synopsis — A brief description of usage, including arguments and options

- Description — A detailed explanation of functionality and operation

- Files — Associated files or directories

- See Also — References to related commands or functions

- Bugs — Known issues or limitations

- Owners — Authors or maintainers

This format represented a new era in documentation—a structured approach that remains relevant today through man pages (short for "manual pages").

Man Pages: Living Fossils of the Digital Age

Both Unix and C language endured, forming the foundation of modern IT infrastructure. Today, man pages continue to evolve within Unix descendants like Linux, FreeBSD, and macOS. For instance, Debian GNU/Linux maintains a policy requiring all packages to include an associated man page for "each program, utility, and function."

This practice exemplifies colocating software with its documentation—a predictable way to navigate new utilities. Modern man pages contain more entries while retaining those original structural principles.

Consider this example of requesting a function man page in Ubuntu Linux:

$ man 3 strdupa

The "3" refers to section 3 of the manual, which covers library calls (functions within program libraries). The output would display:

NAME strdup, strndup, strdupa, strndupa - duplicate a string

LIBRARY Standard C library (libc, -lc)

SYNOPSIS #include <string.h>

char *strdup(const char *s);

char *strndup(const char s[.n], size_t n);

char *strdupa(const char *s);

char *strndupa(const char s[.n], size_t n);...

DESCRIPTION The strdup() function returns a pointer to a new string which is

a duplicate of the string s. Memory for the new string is obtained

with malloc(3), and can be freed with free(3).

The strndup() function is similar, but copies at most n bytes.

If s is longer than n, only n bytes are copied, and a terminating

null byte ('\0') is added.

strdupa() and strndupa() are similar, but use alloca(3) to allocate the buffer.

RETURN VALUE On success, the strdup() function returns a pointer to the duplicated string.

It returns NULL if insufficient memory was available, with errno set

to indicate the error.

ERRORS ENOMEM Insufficient memory available to allocate duplicate string....

By default, this command opens a scrollable pager like less. To print the output directly, you can set the MANPAGER environment variable:

$ MANPAGER=cat man 3 strdupa

The Interface to Manuals

The utility for accessing system reference manuals is simply called man, and it offers numerous capabilities including keyword searching, reference following, and formatting. Naturally, this tool has its own man page:

$ man man

This reveals information about manual sections:

NAME man - an interface to the system reference manuals

SYNOPSIS man [man options] [[section] page ...] ...

man -k [apropos options] regexp ...

man -K [man options] [section] term ...

man -f [whatis options] page ...

man -l [man options] file ...

man -w|-W [man options] page ...

DESCRIPTION man is the system's manual pager. Each page argument given to man is normally

the name of a program, utility or function. The manual page associated

with each of these arguments is then found and displayed. A section, if provided,

will direct man to look only in that section of the manual. The default action

is to search in all of the available sections following a pre-defined

order (see DEFAULTS), and to show only the first page found, even if page exists

in several sections....

The manual sections are organized as follows:

- 1 — Executable programs or shell commands

- 2 — System calls (functions provided by the kernel)

- 3 — Library calls (functions within program libraries)

- 4 — Special files (usually found in /dev)

- 5 — File formats and conventions, e.g. /etc/passwd

- 6 — Games

- 7 — Miscellaneous (including macro packages and conventions), e.g. man(7), groff(7), man-pages(7)

- 8 — System administration commands (usually only for root)

- 9 — Kernel routines [Non standard]

A conventional man page consists of several sections including NAME, SYNOPSIS, CONFIGURATION, DESCRIPTION, OPTIONS, EXIT STATUS, RETURN VALUE, ERRORS, ENVIRONMENT, FILES, VERSIONS, STANDARDS, NOTES, BUGS, EXAMPLE, AUTHORS, and SEE ALSO.

The Evolution of Developer Experience

For decades, man pages were central to system administration and programming. Tools like GNU Emacs (created in 1984) and ViM (first released in 1991) integrated man page access directly into their editors through commands like M-x man and :Man respectively.

These text editors remain popular today, and many developers still maintain the habit of consulting man pages directly from their terminals. However, the widespread adoption of the internet and increasingly sophisticated search engines changed how developers access information.

The nature of search itself evolved. Rather than looking up specific functions or commands, developers now often seek complete solutions to complex problems—such as "How to make a PDF viewer in React?" or "How to balance load in distributed systems?"

While pure documentation lookups remain common, especially for service interfaces and SDKs, web-based searching has become the norm. This has created space for standardized documentation formats like OpenAPI, AsyncAPI, and others. Schemas are now increasingly recognized by IDEs, enabling autocompletion and validation.

The bulk of documentation, however, remains unstructured—written in various formats (including Markdown) with layouts driven by audience preferences and domain-specific needs. Documentation websites have evolved into complex platforms with diverse designs, from embedded system manuals to web framework references.

The AI Conundrum

This ecosystem of documentation formats worked well until the emergence of natural language interfaces with AI systems. This pattern brings us back to the sophisticated editor configurations of the past—knowledgeable users spent countless hours tuning their tools to provide the right information at the right time.

Now, anyone can achieve similar capabilities, provided the AI model is sufficiently advanced. This reveals an interesting paradox: machines have different needs than humans. They don't care about fonts and colors but require structured information.

Modern AI models are improving at reading and understanding arbitrary text, but it remains inefficient—consuming both time and computational resources. When asked why unstructured guides pose challenges, Claude Code (an AI coding assistant from Anthropic) highlighted several key issues:

Context Window Limitations. Unstructured guides often bury critical information in lengthy narratives. When a guide mixes setup instructions, conceptual explanations, troubleshooting, and examples all together, Claude has to process much more text to extract specific actionable information.

Ambiguous Information Hierarchy. In unstructured documentation, it's unclear what's essential vs. supplementary. A tutorial might spend 3 paragraphs on background context before mentioning a critical prerequisite buried in the middle.

Mixed Content Types. Unstructured guides often combine: historical context, conceptual explanations, step-by-step instructions, troubleshooting tips, and personal opinions/recommendations. This makes it harder for Claude to distinguish between "what you need to do" vs. "why this exists" vs. "what might go wrong."

Inconsistent Formatting. Without standardized sections, every guide organizes information differently. One might put examples at the end, another sprinkles them throughout, a third puts them in sidebars. Claude has to adapt its parsing strategy for each document rather than applying consistent patterns.

Missing Cross-References. Unstructured guides might mention related topics in passing but don't provide systematic cross-referencing.

In contrast, Claude Code noted that man pages' structured format offers significant advantages:

With man pages' structured sections, Claude can quickly identify the SYNOPSIS for syntax or EXAMPLES for usage patterns.

Man pages' rigid structure (NAME → SYNOPSIS → DESCRIPTION → OPTIONS) creates predictable information hierarchy that Claude can navigate efficiently.

Man pages include explicit "SEE ALSO" sections that help Claude understand relationships between commands and concepts.

This is why documentation formats like OpenAPI specs, JSON schemas, and yes—50-year-old man pages remain valuable for both humans and AI tools. The structure itself is information.

Looking Forward

Should we rewrite all manuals using groff to make LLMs happy? What will happen to the beautifully designed documentation websites that companies are proud of? And where does that leave SEO? Or should we hope that AI will develop sufficient cognitive power to understand our current documentation formats regardless of structure?

The concept of "helping" AI understand documentation isn't new. Practices like "clues" for LLMs, CLAUDE.md files, and other structured approaches are gaining popularity.

This brings us full circle to the insight that began our journey: the Unix creators from half a century ago established documentation standards that inadvertently created an AI-friendly format. Perhaps we're not witnessing the return of ancient documentation practices but rather discovering their enduring relevance in our new technological landscape.

The past isn't just prologue—it might be the blueprint for our future.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion