MIT chemical engineers have developed an AI model that optimizes genetic sequences in industrial yeast, potentially reducing the cost and time of protein drug development by up to 20%.

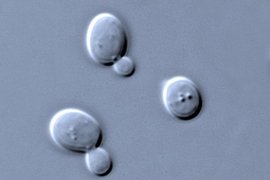

Industrial yeasts like Komagataella phaffii have long been the unsung heroes of biopharmaceutical manufacturing, quietly producing billions of dollars worth of protein drugs and vaccines each year. From insulin to hepatitis B vaccines to cancer-fighting monoclonal antibodies, these microscopic workhorses have been essential to modern medicine. Now, MIT researchers have harnessed artificial intelligence to make these organisms even more efficient, potentially revolutionizing how we develop and manufacture protein-based drugs.

Using a large language model (LLM), the MIT team analyzed the genetic code of K. phaffii, specifically focusing on the codons—three-letter DNA sequences that encode amino acids. While there are only 20 naturally occurring amino acids, there are 64 possible codon sequences, meaning most amino acids can be encoded by multiple codons. The patterns of codon usage vary between organisms, and this variation has been a critical factor in protein production efficiency.

Traditional approaches to codon optimization have relied on selecting the most frequently used codons in the host organism. However, this method has limitations. If the same codon is always used to encode a particular amino acid, the cell may deplete its supply of the corresponding transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, creating bottlenecks in protein production.

To address this challenge, the MIT researchers deployed a sophisticated encoder-decoder model—a type of large language model typically used for text analysis. Instead of analyzing text, they trained the model on DNA sequences from K. phaffii, using data from approximately 5,000 proteins naturally produced by the organism. The model learned the complex relationships between codons, including how they interact when placed next to each other and how distant codons influence one another.

"The model learns the syntax or the language of how these codons are used," explains J. Christopher Love, the Raymond A. and Helen E. St. Laurent Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT. "It takes into account how codons are placed next to each other, and also the long-distance relationships between them."

The researchers tested their AI-optimized sequences against six different proteins, including human growth hormone, human serum albumin, and trastuzumab (a monoclonal antibody used to treat cancer). They also generated optimized sequences using four commercially available codon optimization tools for comparison. When these sequences were inserted into K. phaffii cells, the AI-generated sequences outperformed or matched the best commercial tools for five of the six proteins tested.

This breakthrough could have significant implications for the biopharmaceutical industry. For new biologic drugs—large, complex drugs produced by living organisms—the development process can account for 15 to 20 percent of the overall cost of commercializing the drug. By providing more reliable predictions and reducing the need for laborious experimental tasks, this AI approach could substantially shorten development timelines and reduce costs.

What makes this research particularly exciting is what the model learned beyond its explicit training. When researchers examined the model's internal workings, they discovered it had independently learned important biological principles. For example, the model learned to avoid negative repeat elements—DNA sequences that can inhibit the expression of nearby genes. It also categorized amino acids based on biophysical properties like hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity, demonstrating that it was learning meaningful biological patterns rather than simply optimizing for the specific task it was given.

"Not only was it learning this language, but it was also contextualizing it through aspects of biophysical and biochemical features, which gives us additional confidence that it is learning something that's actually meaningful and not simply an optimization of the task that we gave it," Love notes.

The research team has made their code available to other researchers who wish to use it for K. phaffii or other organisms. They've also tested the approach on datasets from different organisms, including humans and cows, finding that species-specific models are needed to optimize codons for target proteins effectively.

This work represents a significant step forward in applying artificial intelligence to biological systems. By treating genetic sequences as a language to be learned and optimized, the researchers have opened new possibilities for improving the efficiency of protein production. As the biopharmaceutical industry continues to grow and evolve, such innovations could play a crucial role in making life-saving drugs more accessible and affordable.

The research was funded by the Daniel I.C. Wang Faculty Research Innovation Fund at MIT, the MIT AltHost Research Consortium, the Mazumdar-Shaw International Oncology Fellowship, and the Koch Institute. As this technology continues to develop, it may well become a standard tool in the biopharmaceutical industry's arsenal, helping to bring new treatments to patients more quickly and cost-effectively than ever before.

For more information about this research, visit the Love Lab website or read the full paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion