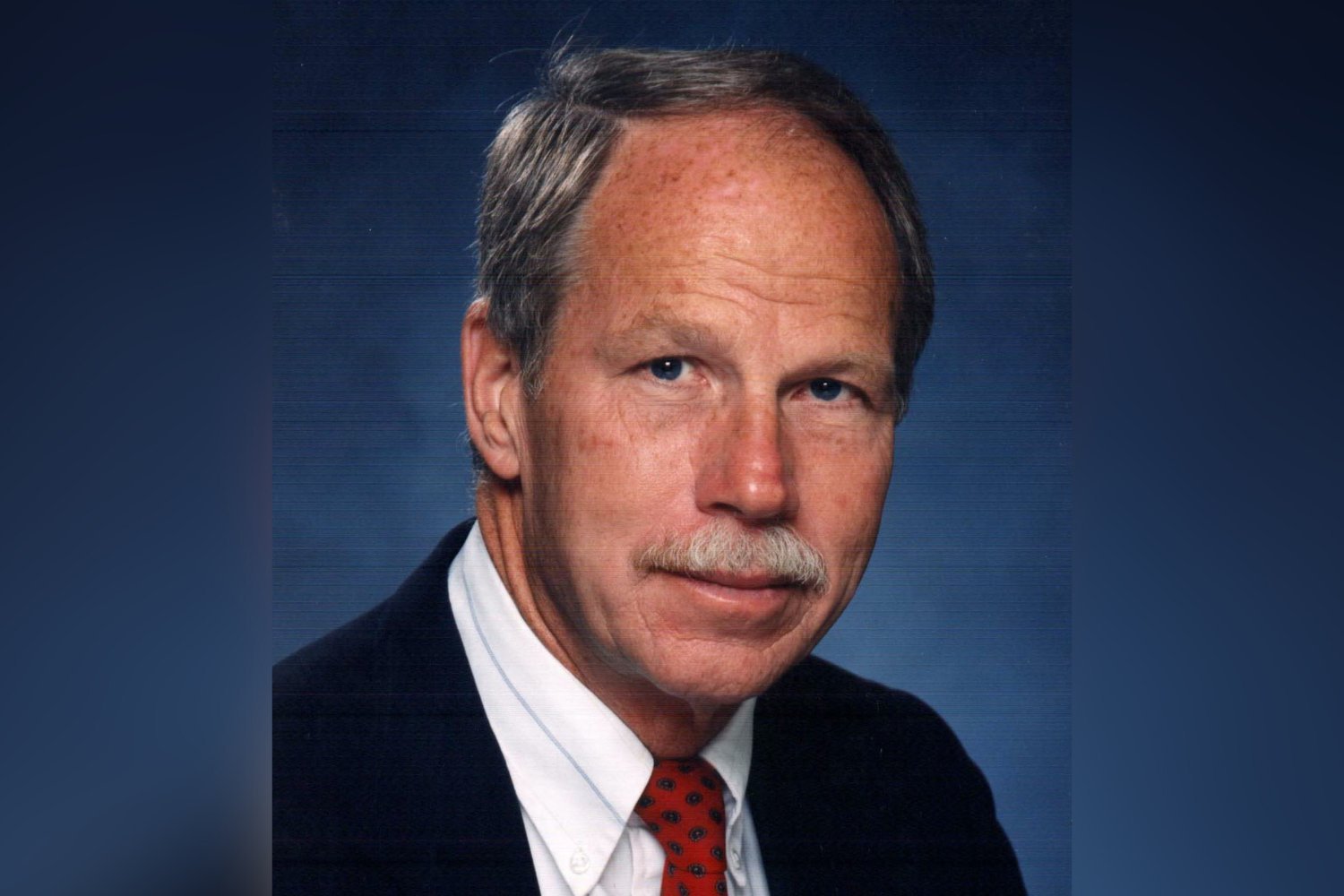

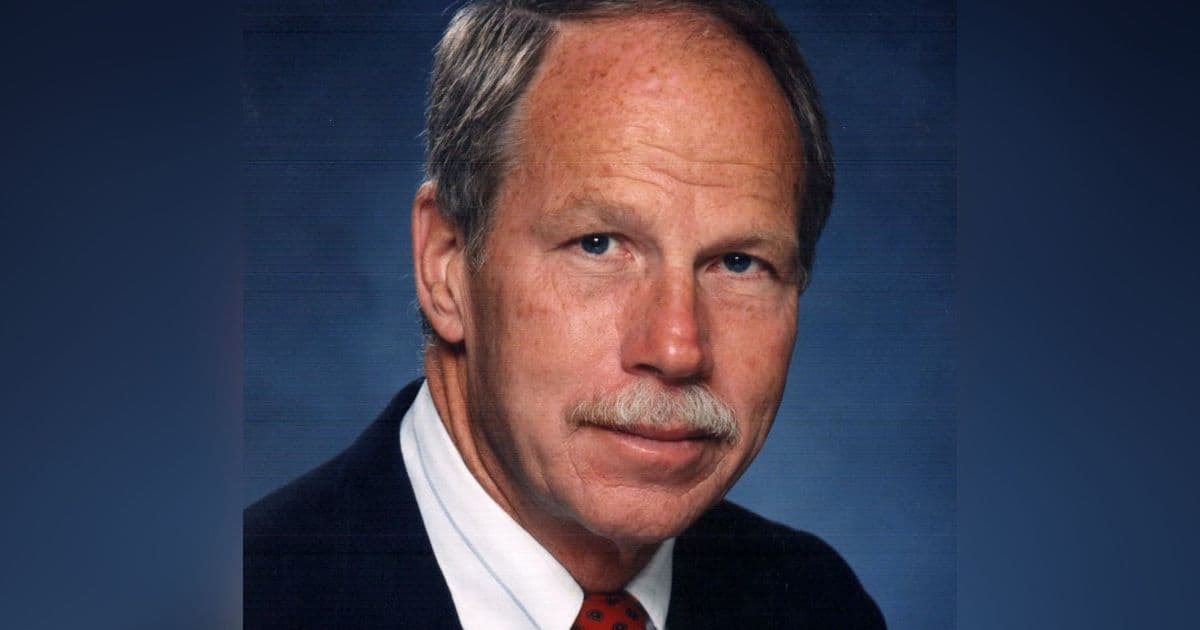

Robert Liebeck, a pioneer in blended-wing body aircraft design and mentor to generations of aerospace engineers, passed away on January 12 at the age of 87. His five-decade career at Boeing and subsequent role at MIT left an indelible mark on modern aircraft design, from high-altitude reconnaissance planes to Formula One aerodynamics.

The aerospace engineering community lost one of its most influential figures this month with the passing of Robert Liebeck, a professor of the practice in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Liebeck, who died on January 12 at age 87, was a foundational contributor to aircraft design whose work on blended-wing body (BWB) configurations and high-lift airfoils shaped both commercial aviation and motorsport aerodynamics.

"Bob was a mentor and dear friend to so many faculty, alumni, and researchers at AeroAstro over the course of 25 years," says Julie Shah, department head and the H.N. Slater Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT. "He'll be deeply missed by all who were fortunate enough to know him."

Liebeck's career began with graduate research into high-lift airfoils, resulting in novel designs that became known as "Liebeck airfoils." These airfoils are primarily used in high-altitude reconnaissance airplanes but have been adapted for unexpected applications, including Formula One racing cars, racing sailboats, and even a flying replica of a giant pterosaur. The airfoil's design principle—optimizing the pressure distribution over a surface to maximize lift while minimizing drag—proved versatile enough to cross traditional engineering boundaries.

His most significant contribution to aviation, however, was his pioneering work on blended-wing body aircraft. During his five-decade tenure at Boeing, where he retired as senior technical fellow in 2020, Liebeck oversaw the BWB project and collaborated closely with NASA on the X-48 experimental aircraft. The BWB configuration represents a radical departure from conventional tube-and-wing aircraft, integrating the fuselage, wings, and engine nacelles into a single lifting surface. This design promises substantial fuel efficiency improvements—potentially 20-30% over traditional aircraft—by reducing wetted area and improving aerodynamic efficiency.

After retiring from Boeing, Liebeck continued advancing BWB technology as a technical advisor at JetZero, a startup aiming to build more fuel-efficient aircraft for both military and commercial use. JetZero has set a target date of 2027 for its demonstration flight, building directly on Liebeck's decades of research. The company's approach reflects Liebeck's philosophy of bridging theoretical aerodynamics with practical engineering constraints.

Liebeck's influence extended beyond BWB research into motorsport aerodynamics. "In addition to aviation, Bob was very significant in car racing and developed the downforce wing and flap system which has become standard on F1, IndyCar, and NASCAR cars," notes John Hansman, the T. Wilson Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT. This contribution demonstrates how aerospace principles can transform other engineering fields when applied with deep understanding of fluid dynamics.

Appointed as professor of the practice at MIT in 2000, Liebeck taught aircraft design and aerodynamics courses. His teaching philosophy emphasized practical application alongside theoretical understanding. "Bob contributed to the department both in aircraft capstones and also in advising students and mentoring faculty, including myself," Hansman adds.

Liebeck's mentorship shaped significant research projects, including his advisory role on the Silent Aircraft Initiative, a collaboration between MIT and Cambridge University led by Dame Ann Dowling. He also worked closely with Professor Woody Hoburg '08 and his research group, advising on efficient methods for designing aerospace vehicles. Before Hoburg was accepted into the NASA astronaut corps in 2017, the group produced GPkit, an open-source Python package for geometric programming used to design a five-day endurance unmanned aerial vehicle for the U.S. Air Force.

The technical significance of Liebeck's work lies in his ability to identify and solve fundamental aerodynamic problems that had broad applicability. His high-lift airfoil research addressed a critical challenge in aircraft design: generating sufficient lift at low speeds for takeoff and landing without excessive drag during cruise. The Liebeck airfoil achieves this through careful shaping of the pressure distribution, creating a high-lift coefficient while maintaining good performance across a range of operating conditions.

For BWB aircraft, Liebeck's contributions addressed the complex trade-offs between aerodynamic efficiency, structural weight, and practical cabin design. Traditional aircraft separate the passenger cabin (a pressure vessel) from the lifting surfaces, but BWB designs integrate these functions. This creates challenges in structural design, emergency evacuation, and passenger comfort that Liebeck's work helped to address through iterative design and testing.

His recognition in the field was extensive. Liebeck was an AIAA honorary fellow and Boeing senior technical fellow, as well as a member of the National Academy of Engineering, Royal Aeronautical Society, and Academy of Model Aeronautics. He received the Guggenheim Medal and ASME Spirit of St. Louis Medal, among many other awards, and was inducted into the International Air and Space Hall of Fame.

Beyond his technical achievements, Liebeck was known for his adventurous nature and generosity of spirit. An avid runner and motorcyclist, he approached engineering with the same curiosity and enthusiasm that marked his personal pursuits. This mindset likely contributed to his ability to see connections between disparate fields—applying aircraft aerodynamics to racing cars and even prehistoric flying reptiles.

"It is the one job where I feel I have done some good — even after a bad lecture," Liebeck told AeroAstro Magazine in 2007. "I have decided that I am finally beginning to understand aeronautical engineering, and I want to share that understanding with our youth." This humility and dedication to education defined his later career, even as he remained active in cutting-edge research.

Liebeck's legacy extends through the students he taught, the researchers he mentored, and the aircraft designs that continue to evolve from his foundational work. The BWB concept, once considered experimental, is now being pursued by multiple companies and research institutions worldwide. His airfoil designs continue to be studied and adapted for new applications. The geometric programming tools his students developed are used by aerospace designers globally.

The practical impact of his work is evident in the ongoing development of more efficient aircraft. As the aviation industry faces pressure to reduce emissions, Liebeck's BWB research provides a pathway to significantly more fuel-efficient designs. The technical challenges he helped identify and address—structural integration, aerodynamic optimization, and practical cabin design—remain central to current research efforts.

Liebeck's career demonstrates how deep technical expertise, combined with practical engineering insight, can drive innovation across multiple domains. From the high-altitude reconnaissance planes using his airfoils to the Formula One cars employing his downforce systems, his contributions span the full spectrum of aerodynamic applications. His work at Boeing and MIT created a bridge between theoretical research and industrial application, a model that continues to guide aerospace engineering education and practice.

The aerospace community will feel his absence not just in the loss of a technical leader, but in the loss of a mentor who understood that engineering progress depends as much on sharing knowledge as on creating it. His influence will persist through the designs he pioneered, the students he inspired, and the colleagues who continue the work he began.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion