Scientists have discovered that a low dose of the discontinued antibiotic cephaloridine can induce beneficial metabolites in gut bacteria, extending lifespan in both nematodes and mice. This research reveals a novel pathway for microbiota-based therapeutics that bypass traditional antibiotic mechanisms to promote host health.

Repurposing Antibiotics: How Low-Dose Cephaloridine Extends Lifespan by Rewiring Gut Bacteria

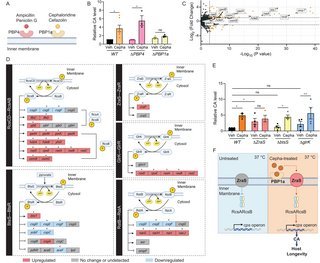

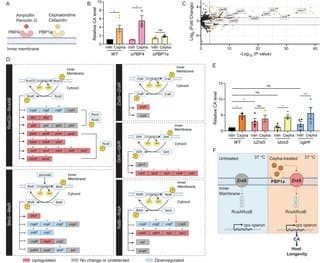

The human gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, has emerged as a critical regulator of health and longevity. While we've known for years that diet influences this microbial community, a groundbreaking new study published in PLoS Biology reveals a surprising approach: using a specific chemical compound to rewire gut bacteria into producing longevity-promoting metabolites. Researchers have discovered that low-dose cephaloridine—a discontinued antibiotic—can induce the production of colanic acid (CA) in commensal E. coli, extending lifespan in both nematode and mammalian models without exerting its typical antimicrobial effects.

{{IMAGE:2}}

The Longevity Connection in the Gut Microbiome

The study began with an intriguing observation: centenarians showed a modest but statistically significant increase in the abundance of the capsular polysaccharide synthesis (cps) operon in their gut microbiomes compared to elderly controls. The cps operon encodes enzymes for producing colanic acid, an extracellular polysaccharide previously linked to longevity in model organisms.

"This was a critical starting point," explains the research team. "While the cps operon is present in less than 1% of gut microbial species, its enrichment in centenarians suggested a potential role in healthy aging."

Discovering the Chemical Inducer

The researchers screened various antibiotics to identify compounds that could activate the cps operon in E. coli at 37°C—temperatures that normally suppress CA production. Their screening revealed that cephaloridine, a first-generation cephalosporin antibiotic discontinued in the 1970s due to poor oral absorption and nephrotoxicity, was uniquely effective at inducing CA production at sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MIC).

{{IMAGE:5}}

"What's remarkable is that cephaloridine was effective at concentrations as low as 1.8 μg/mL—what we termed the 'Colanic Acid-Inducing dose' (Cepha-CAI dose)," the researchers note. "At this concentration, the bacteria showed no growth inhibition or metabolic suppression, yet produced seven times more colanic acid than untreated controls."

From Lab Models to Therapeutic Potential

The team first tested their approach in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), a nematode model organism frequently used in aging research. When nematodes were fed E. coli treated with the Cepha-CAI dose, they exhibited a 14% extension in lifespan compared to controls—a significant increase in the context of aging research.

Encouraged by these results, the researchers moved to mammalian models. Using a genetically engineered E. coli strain with fluorescent reporters for cps operon activity, they demonstrated that oral administration of low-dose cephaloridine effectively induced CA production in the mouse gut at physiological temperatures.

{{IMAGE:3}}

"The fact that cephaloridine could overcome the temperature restriction on CA production in the mammalian gut was a major breakthrough," the researchers state. "This suggested we could target commensal bacteria in a living host to produce beneficial metabolites."

Metabolic Benefits in Aging Mice

In a six-month study with aging mice, the team observed significant metabolic improvements in animals treated with low-dose cephaloridine. Notably, the treatment attenuated age-related increases in LDL cholesterol in male mice and insulin levels in female mice. The LDL/HDL ratio—a key marker of cardiovascular health—remained more stable in treated mice compared to controls.

Importantly, metagenomic analysis of fecal samples revealed no reduction in microbiome richness, indicating that the low-dose treatment didn't cause the broad-spectrum disruption typical of antibiotic therapy.

Uncovering the Molecular Mechanism

The most fascinating aspect of this research is the mechanism by which cephaloridine induces CA production. The team discovered that the compound acts through two key bacterial proteins: PBP1a (penicillin-binding protein 1a) and ZraS (a membrane-bound histidine kinase).

{{IMAGE:4}}

"Unlike its known antibiotic mechanism, cephaloridine's effect on CA production doesn't involve the canonical RcsC-RcsD two-component system that normally regulates cps operon expression at lower temperatures," the researchers explain. "Instead, we found that cephaloridine binding to PBP1a activates ZraS, which then promotes RcsAB-mediated transcription of the cps operon."

This pathway represents a previously unrecognized signaling mechanism in bacteria, where a compound typically associated with cell wall synthesis instead triggers the production of a beneficial metabolite.

Implications for Microbiome-Based Therapeutics

This research opens new avenues for developing microbiota-targeted therapeutics. The approach leverages "host-impermeable drugs"—compounds that remain primarily within the gastrointestinal tract—to specifically modulate bacterial metabolism without directly affecting host cells.

"The beauty of this approach is its specificity," the researchers note. "Cephaloridine's poor oral absorption makes it ideal for targeting gut bacteria without systemic effects. Moreover, we've identified a specific bacterial pathway (ZraS-RcsAB) that could be targeted by other compounds to induce beneficial metabolites."

Beyond Antibiotics: A New Frontier in Drug Development

The study challenges conventional drug discovery paradigms that focus primarily on eukaryotic targets. By demonstrating that a compound can be repurposed to modulate bacterial metabolism for host benefit, the researchers highlight the untapped potential of the microbiome as a therapeutic target.

"We're entering an era where we can think of drugs not just as targeting human cells, but as potentially targeting our microbial partners," the team concludes. "This research provides a blueprint for developing 'microbiota modulators'—drugs that enhance the production of beneficial microbial metabolites to promote health and longevity."

As the field of microbiome therapeutics continues to evolve, this study represents a significant step toward precision interventions that harness the power of our microbial symbionts. The discovery that a low dose of a discontinued antibiotic can extend lifespan by rewiring gut bacteria metabolism underscores the complexity and potential of the human microbiome as a frontier for medical innovation.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion