Wesley Moore explores the Loongson 3A6000 CPU and the MOREFINE M700S mini-PC, documenting the process of installing Chimera Linux and assessing the performance, compatibility, and future of the LoongArch architecture in the open-source ecosystem.

The landscape of computing architectures has narrowed dramatically over the past few decades. Once a vibrant ecosystem of competing instruction sets—Alpha, MIPS, SPARC, PowerPC, and others—has largely consolidated around x86_64 for desktops and servers, and ARM for mobile and increasingly for laptops. This homogenization, while efficient, reduces diversity and can create vulnerabilities in the global technology supply chain. It is against this backdrop that the emergence of LoongArch, a new 64-bit RISC architecture developed by Loongson Technology, becomes particularly noteworthy. It represents a deliberate effort to create a homegrown, patent-unencumbered ISA for the Chinese market, but its broader significance lies in its potential to reintroduce architectural diversity into the mainstream computing world, particularly within the Linux ecosystem.

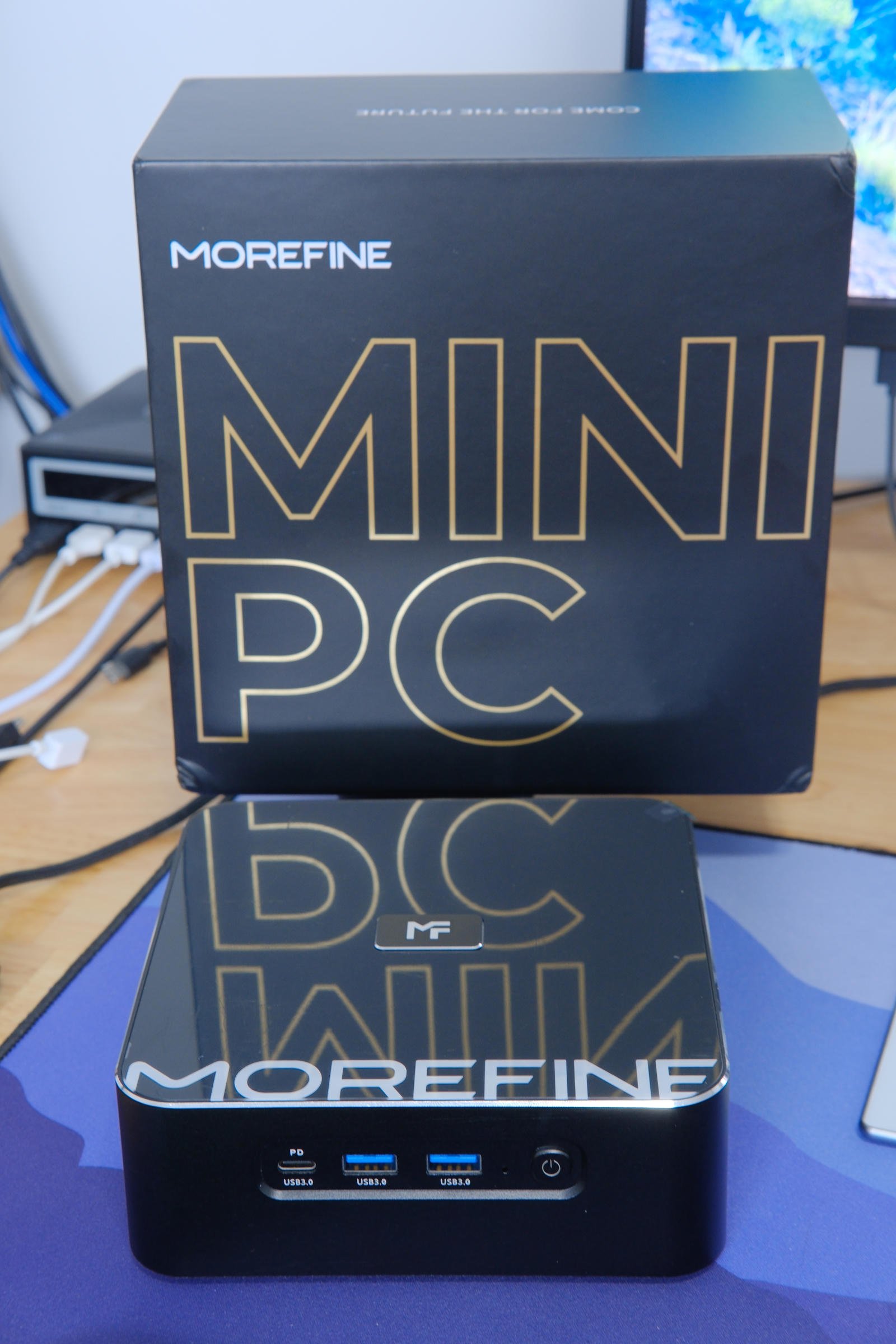

The hardware at the center of this exploration is the MOREFINE M700S, a compact mini-PC powered by the Loongson 3A6000 CPU. This processor is a quad-core, eight-thread design running at 2.5 GHz, built on the LoongArch64 ISA. LoongArch64 is a 64-bit RISC architecture inspired by elements of MIPS and RISC-V, featuring 32 general-purpose registers, 32 floating-point registers, and support for two vector extensions: LSX (128-bit) and LASX (256-bit). The rationale behind its creation, as noted in its documentation, was to achieve technological independence without infringing on existing patents. This positions it not as a direct competitor to ARM or x86 in the global market, but as a sovereign alternative with a distinct architectural philosophy.

The M700S itself is a well-constructed aluminum box, roughly the size of an original Mac mini, with a generous array of ports: USB 3.0 Type-C and Type-A on the front, and four USB 2.0 ports, two HDMI outputs (supporting 4K at 30Hz), two Gigabit Ethernet ports, and a 3.5mm audio jack on the back. Internally, it houses 16GB of DDR4 RAM (with one slot free), an M.2 slot for NVMe storage, and a large blower fan for cooling. The fan, however, is a notable point of contention; it runs constantly at a high speed, making the system significantly noisier than comparable mini-PCs. When inquired, the manufacturer confirmed this is by design and not adjustable, a trade-off for cooling the 65W TDP chip.

The system arrived with Loongnix, a Debian-based distribution with KDE, but its components were dated and the project's online presence appeared inactive. The goal was to install Chimera Linux, a rolling-release distribution the author maintains, which has official support for loongarch64. The process began with configuring the UEFI, which defaults to Chinese. By navigating to the language selector on the first boot screen, one can switch to English, making the installation process straightforward. Booting from a Chimera Linux ISO and following the standard installation procedure revealed a key advantage: the loongarch64 installation is functionally identical to an x86_64 install, right down to using systemd-boot. This seamless integration stands in stark contrast to the often-fragmented support for newer ARM platforms like the Snapdragon X series.

With the base system installed, the first challenge emerged with the graphical desktop. While the system would boot and allow login to GNOME or Wayfire, it would promptly crash back to the login screen. Wayfire logs revealed EGL initialization failures: "DRI2: failed to create screen" and "DRI2: failed to load driver". This points to immature or incomplete graphics driver support for the Loongson LG100 GPU in the current Mesa stack. The solution was to fall back to the X.Org server, where an Xfce X11 session ran without issue. This experience highlights a common theme for emerging architectures: the core kernel and userland may be stable, but the graphics stack, being complex and hardware-specific, often lags behind.

Performance and efficiency are where the Loongson 3A6000 shows its current limitations. At idle, the system draws about 27W, climbing to 65W under load. For context, an Intel N100-based mini-PC idles at ~7W. In browser benchmarks, the M700S scores 4.45 on Speedometer 3.1, compared to 12.7 for the N100. A Rust build test (the allsorts crate) took 44 seconds on the LoongArch machine versus 22 seconds on a high-end AMD Ryzen 9950X3D. While not a powerhouse, the system is perfectly usable for general tasks like web browsing, terminal work, and light development. It feels subjectively faster than a Raspberry Pi 400, making it a viable, if not exceptional, desktop machine.

The primary motivation for acquiring this hardware was to test software compatibility and address build issues within the Chimera Linux ports collection. A survey of broken packages revealed a manageable list, mostly Rust projects. The common thread was outdated dependencies, particularly the nix and rustix crates, which lack support for the loongarch64 architecture. For instance, the spotify-player and systeroid packages are blocked by an unmaintained pure-Rust version of the protobuf-parse crate (v3.x), which depends on an old rustix. The maintainers of the newer protobuf v4.x crate, now backed by Google, have taken a different approach with C dependencies, creating a fork in the ecosystem.

This dependency chain issue is a microcosm of the challenges facing niche architectures. The fix often requires upstream maintainers to update their dependency trees, a process that can be slow or stalled if the project is not actively maintained. In some cases, like the tiny IRC client, the fix was straightforward: updating the nix crate in the package definition. For others, like halloy, a new upstream release that updated the problematic ring crate resolved the issue. The author's work on these packages demonstrates the iterative, community-driven process required to achieve full software compatibility on a new platform.

In conclusion, the journey of running Linux on a LoongArch mini-PC is a testament to the maturity of the Linux kernel and core userland in supporting diverse architectures. The installation process was smooth, and the system is functional for daily use, albeit with some compromises in graphics and performance. The real work lies in the long tail of application software, where dependency management and hardware-specific drivers present ongoing hurdles. The existence of LoongArch, however, is a positive development for the open-source world. It provides a new, accessible target for development, encourages architectural diversity, and serves as a practical testbed for the portability of software. As the ecosystem around it grows, it may well carve out its own niche, proving that there is still room for new ideas in the established world of computing architectures.

For more details on LoongArch, see the Introduction to LoongArch on kernel.org. The MOREFINE M700S is available from various retailers, including AliExpress.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion