A whimsical explanation of the BEAM virtual machine's architecture using gnomes, mailboxes, and scrolls to illustrate process isolation, message passing, and fault tolerance.

The Mental Luggage Problem

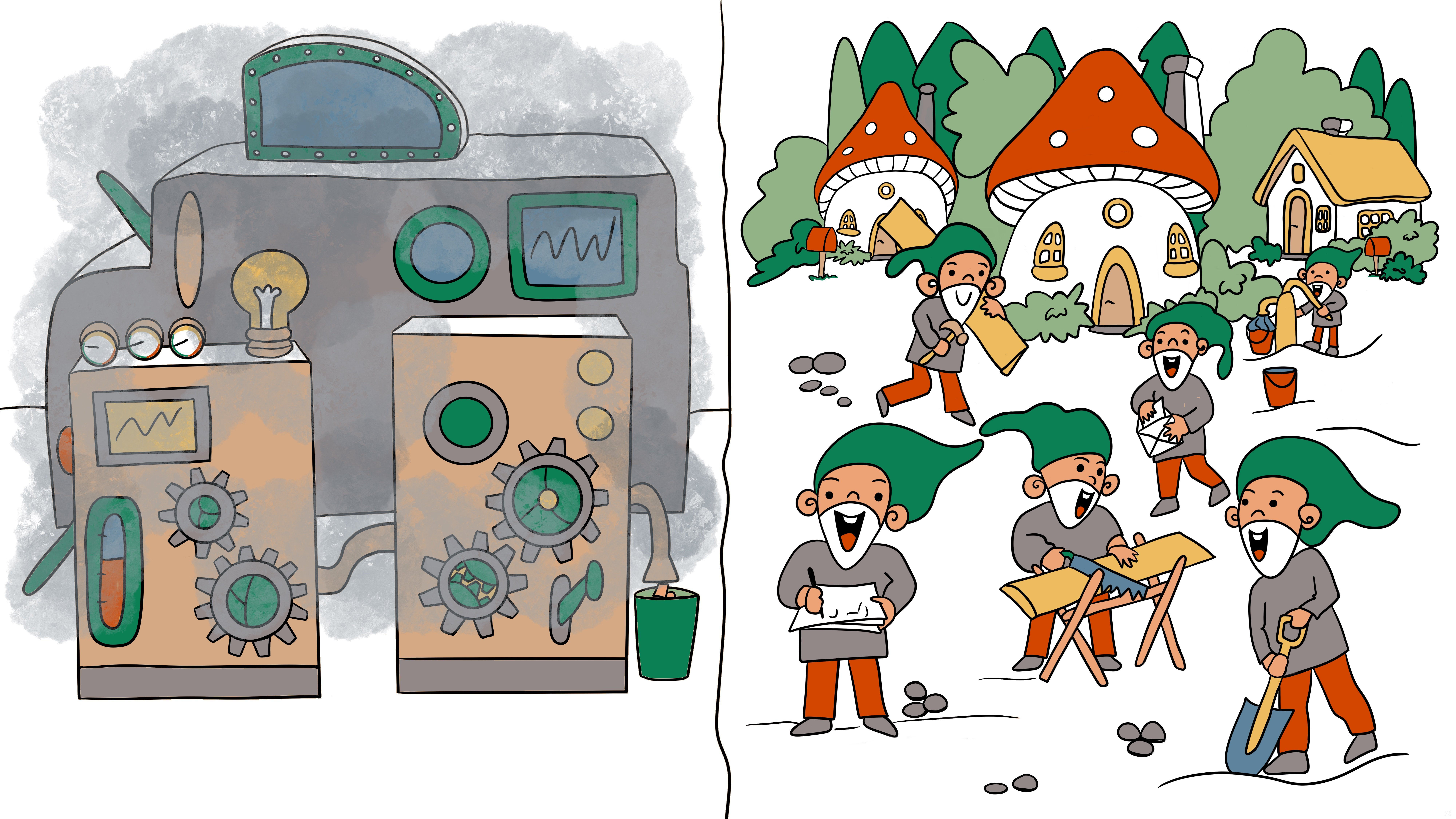

Many developers arrive at the BEAM ecosystem carrying baggage from object-oriented programming. They conflate code with processes, imagining classes and objects as living entities. This confusion persists even among experienced practitioners who occasionally equate modules with processes. To dismantle this mental model, I created the Gnome Village metaphor.

The Gnome Village - each worker operates independently

The Gnome Village - each worker operates independently

Gnomes vs Machines

Object-oriented systems resemble intricate machines: interconnected parts with tight couplings. The BEAM model differs fundamentally. Code resides in scrolls, state lives inside gnomes, and communication occurs solely through message protocols. You deploy thousands of microscopic workers sharing nothing.

Contrasting machine-like architectures with the gnome village model

Contrasting machine-like architectures with the gnome village model

Anatomy of a Gnome

A gnome represents a BEAM process—distinct from OS threads or shared-memory fibers. Each gnome lives, performs tasks, and eventually dies. Crucially, its actions never corrupt another's memory. This isolation guarantees that local failures remain local.

Private Memory: The Gnome Backpack

Every gnome carries a backpack holding personal belongings: data structures, variables, and execution context. This is BEAM's per-process heap. No other gnome may peer inside, not even supervisors.

Each gnome manages its own memory backpack

Each gnome manages its own memory backpack

Memory management is elegantly localized:

- Gnomes expand their backpacks when needed

- Garbage collection pauses only the reorganizing gnome

- Arguments over shared resources vanish since workers copy small scrolls rather than contend for access

This autonomy enables scaling: when a gnome cleans its backpack, others continue uninterrupted.

Communication Protocol: Mail, Not Shared Drawers

Gnomes cooperate through asynchronous messages, never shared memory. Each has a mailbox where communications queue until processed. This eliminates interrupts and memory contention.

Message passing via mailboxes replaces shared memory

Message passing via mailboxes replaces shared memory

Key advantages:

- Message copying avoids shared-state chaos

- Large binaries transfer by reference for efficiency

- Mailbox growth visibly indicates bottlenecks

- Copying scales linearly; contention scales exponentially

Shared Scrolls: Code as Community Knowledge

All gnomes reference a central scroll shelf containing code modules. This separates logic from state—unlike OOP's fused objects.

Shared scrolls provide common instructions

Shared scrolls provide common instructions

Critical implications:

- Code updates don't require restarting processes

- New gnomes reference updated scrolls automatically

- Old processes complete work with original versions

- Zero-downtime deployments become natural

Scaling the Village

Spawning processes resembles hiring gnomes. Each arrives with an empty backpack and scroll reference. BEAM's lightweight processes thrive because:

- Memory ownership eliminates cleanup coordination

- Process isolation removes resource contention

- Failures don't propagate

Consequently, Erlang systems handle millions of concurrent activities through massive parallelism rather than raw compute power.

Workbench Scheduling

Gnomes take turns at workbenches (CPU cores) using reduction-based scheduling:

- Turns measured by function calls (reductions)

- Automatic yielding after thousands of reductions

- Microsecond-level context switches

This ensures:

- No single gnome monopolizes resources

- Predictable latency profiles

- Continuous progress during long operations

Failure Containment

The village withstands failures through isolation:

- Crashed gnomes don't corrupt others

- Supervisors restart workers cleanly

- Shared state doesn't exist to become corrupted

Contrast this with threaded models where single failures often cascade. The "let it crash" philosophy succeeds because failure domains match process boundaries.

Conclusion

The gnome village demonstrates BEAM's core principles:

- Processes as units of work, state, and failure

- Messaging as the sole communication channel

- Isolation enabling fault tolerance

- Share-nothing architecture scaling linearly

By embracing small, single-purpose workers communicating through protocols, we build systems resilient to real-world chaos—where crashes become manageable events rather than catastrophes.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion