Google Research challenges the assumption that more AI agents always improve performance, revealing that multi-agent coordination dramatically boosts parallelizable tasks but can severely degrade sequential ones.

When building AI agent systems, the conventional wisdom has been simple: more agents equal better results. A central orchestrator delegating tasks to specialized workers should, in theory, outperform a single agent every time. But new research from Google challenges this assumption, revealing that the relationship between agent count and performance is far more nuanced than previously thought.

The Problem with "More Agents"

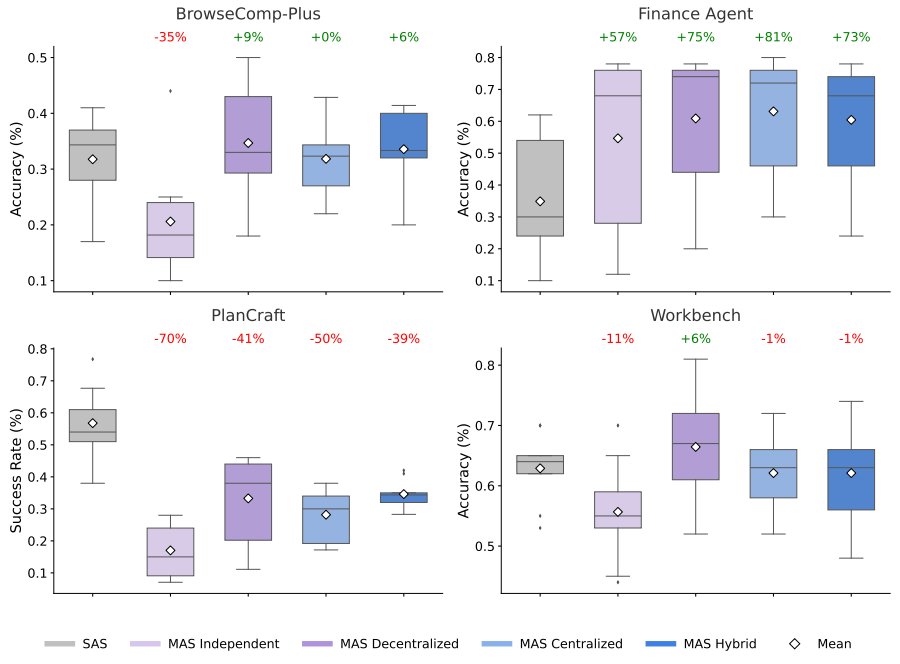

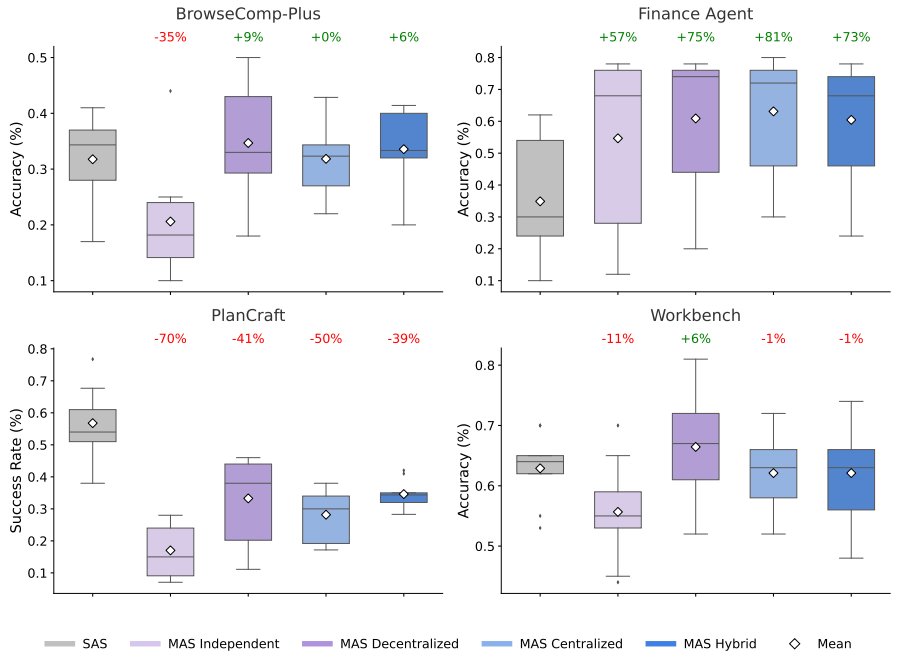

Through a large-scale controlled evaluation of 180 agent configurations, Google Research has derived the first quantitative scaling principles for AI agent systems. The findings are striking: while multi-agent coordination can improve performance on parallelizable tasks by up to 81%, it can also degrade performance on sequential tasks by as much as 70%.

This isn't just academic theory. As AI agents become increasingly common in real-world applications—from coding assistants to personal health coaches—understanding when and how to deploy them effectively becomes critical. The shift from single-shot question answering to sustained, multi-step interactions means that a single error can cascade throughout an entire workflow, making architectural decisions paramount.

What Makes a Task "Agentic"?

To understand scaling behavior, the researchers first defined what makes a task truly "agentic." Unlike traditional static benchmarks that measure a model's knowledge, agentic tasks require:

- Sustained multi-step interactions with an external environment

- Iterative information gathering under partial observability

- Adaptive strategy refinement based on environmental feedback

The team evaluated five canonical architectures across four diverse benchmarks: Finance-Agent (financial reasoning), BrowseComp-Plus (web navigation), PlanCraft (planning), and Workbench (tool use).

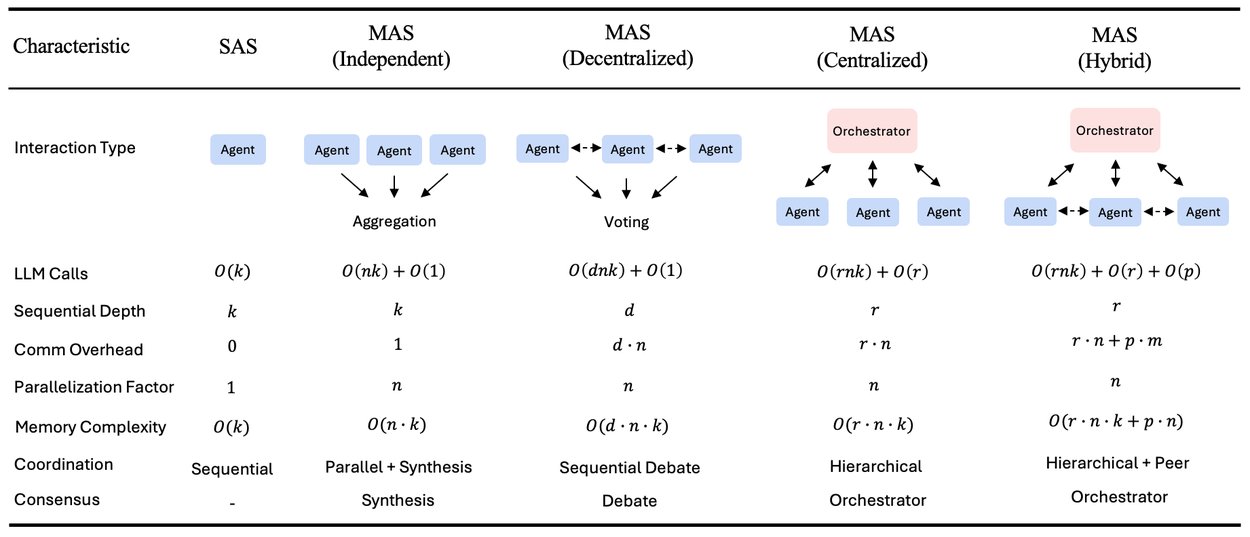

The Five Architectures Tested

- Single-Agent (SAS): A solitary agent executing all reasoning and acting steps sequentially with unified memory

- Independent: Multiple agents working in parallel on sub-tasks without communication, aggregating results only at the end

- Centralized: A "hub-and-spoke" model where a central orchestrator delegates tasks to workers and synthesizes their outputs

- Decentralized: A peer-to-peer mesh where agents communicate directly to share information and reach consensus

- Hybrid: A combination of hierarchical oversight and peer-to-peer coordination

The Results: When More Agents Help (and When They Hurt)

The data reveals a complex relationship between task structure and agent architecture. On parallelizable tasks like financial reasoning—where distinct agents can simultaneously analyze revenue trends, cost structures, and market comparisons—centralized coordination improved performance by 80.9% over a single agent. The ability to decompose complex problems into sub-tasks allowed agents to work more effectively.

However, on tasks requiring strict sequential reasoning (like planning in PlanCraft), every multi-agent variant tested degraded performance by 39-70%. In these scenarios, the overhead of communication fragmented the reasoning process, leaving insufficient "cognitive budget" for the actual task.

The Tool-Use Bottleneck

The research also identified a "tool-coordination trade-off." As tasks require more tools (e.g., a coding agent with access to 16+ tools), the coordination overhead increases disproportionately. This "tax" of coordinating multiple agents grows faster than the benefits they provide.

Architecture as a Safety Feature

Perhaps most importantly for real-world deployment, the study found a relationship between architecture and reliability. The team measured "error amplification"—the rate at which a mistake by one agent propagates to the final result.

Independent multi-agent systems (agents working in parallel without talking) amplified errors by 17.2x. Without a mechanism to check each other's work, errors cascaded unchecked. Centralized systems (with an orchestrator) contained this amplification to just 4.4x. The orchestrator effectively acts as a "validation bottleneck," catching errors before they propagate.

A Predictive Model for Agent Design

Moving beyond retrospective analysis, the researchers developed a predictive model (R² = 0.513) that uses measurable task properties like tool count and decomposability to predict which architecture will perform best. This model correctly identifies the optimal coordination strategy for 87% of unseen task configurations.

This represents a significant shift from heuristic-based design to principled engineering decisions. Instead of guessing whether to use a swarm of agents or a single powerful model, developers can now look at the properties of their task—specifically its sequential dependencies and tool density—to make informed choices.

The Alignment Principle

The research reveals what the team calls the "alignment principle": multi-agent systems work best when the architecture matches the task's inherent structure. Parallelizable tasks benefit from decomposition and parallel execution, while sequential tasks suffer from the coordination overhead.

Implications for the Future of AI Agents

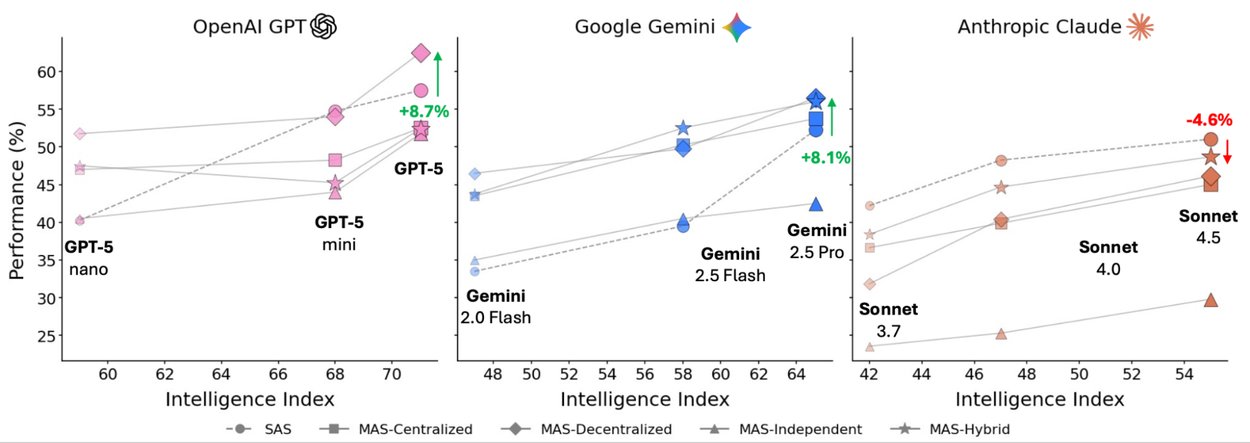

As foundational models like Gemini continue to advance, this research suggests that smarter models don't replace the need for multi-agent systems—they accelerate it, but only when the architecture is right. The key insight is that we're moving from a world where "more agents" was assumed to be better to one where architectural decisions are based on quantitative principles.

This represents a maturation of the field. Rather than treating agent systems as black boxes where adding more components automatically improves performance, we now have a science for understanding when and why these systems work. The next generation of AI agents won't just be more numerous—they'll be smarter, safer, and more efficient because they're built on a foundation of empirical understanding rather than assumptions.

The research team included contributions from Google Research, Google DeepMind, and academic collaborators, marking a significant step toward establishing a "science of scaling" for AI agent systems.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion