A deep dive into an excerpt from Drew Hoskins' new O'Reilly book, 'The Product-Minded Engineer,' exploring how well-crafted errors and warnings are not just technical details but the primary user experience for developers and end-users alike.

The trend of hiring "product engineers" who blend software engineering with product thinking is accelerating, especially in AI-native startups where engineers must specify what AI tools should build. But how do you develop that product muscle? Drew Hoskins, a former software engineer at Microsoft, Facebook, and Stripe, and now a Staff Product Manager at Temporal, has written a guide: "The Product-Minded Engineer" (O'Reilly).

In a recent issue of The Pragmatic Engineer, Gergely Orosz shared an exclusive excerpt from the book's third chapter, "Errors and Warnings." The core thesis is deceptively simple yet profound: for many applications, diagnostics are the primary interface. Users spend most of their time dealing with errors and progressing to the next one.

The Product-Level View of Errors

Hoskins argues that because errors don't appear in marketing screenshots, they are often "out of sight and out of mind" during design. This is a critical blind spot, especially now with autonomous AI agents. An agent presented with a vague error message will fail, wasting time and compute cost. The message isn't just for humans; it's the instruction set for the machine.

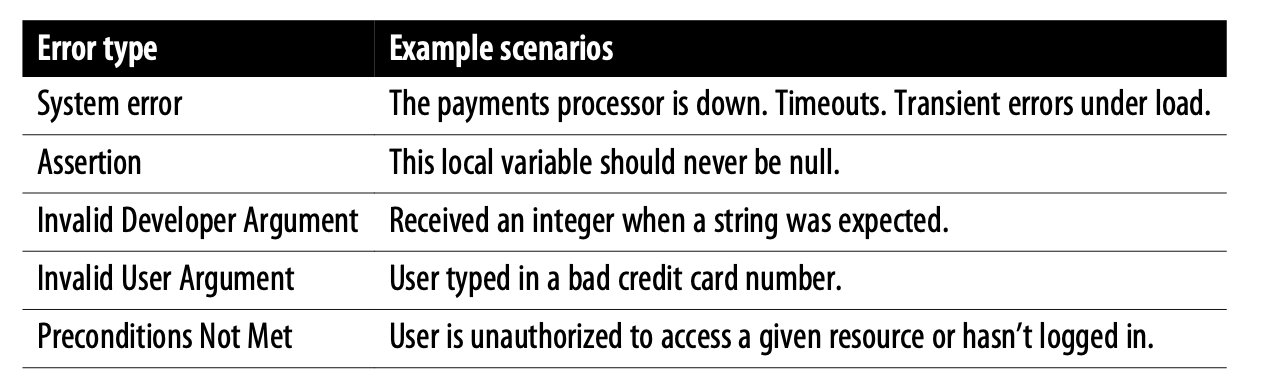

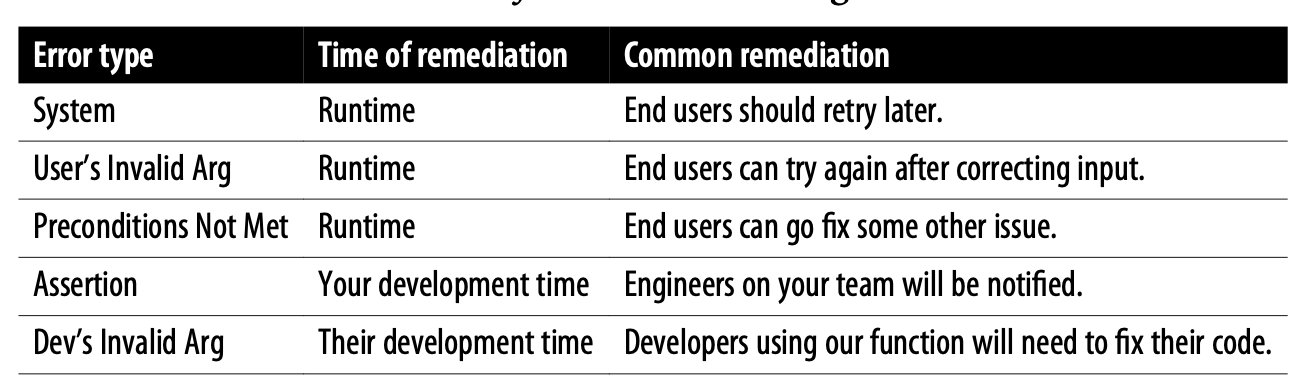

The excerpt introduces a framework for categorizing errors, which is the first step in writing better ones. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, you must identify the audience and the scenario. The book outlines five primary categories:

- System Errors: Unforeseen failures in the system itself (e.g., a database outage).

- User's Invalid Argument: The user provided input that is syntactically or semantically wrong for their intent.

- Precondition Not Met: The user's action is valid, but the system state prevents it (e.g., insufficient permissions).

- Developer's Invalid Argument: A developer using your API or library provided incorrect input.

- Assertion: A bug in your code, caught during development or testing.

Categorizing an error dictates its audience and the appropriate response. An Assertion is for your team and should be caught in testing. A User's Invalid Argument is for the end-user and must be actionable. A Precondition Not Met error needs to be tailored to the user's persona—an administrator gets different instructions than a standard user.

Crafting Actionable Messages

The goal of a diagnostic message is to answer two questions for the user:

- What precisely happened, in terms from the product's ontology?

- What can they do about it?

Hoskins uses a fictional SaaS company, Channelz (a Slack/Discord competitor), as a case study. A common failure is passing an invalid channel name. A poor error message might be:

Cannot deliver a Channelz message to channel '@barnyard-friends': channel does not exist.

This is accurate but unhelpful. The user likely meant #barnyard-friends (a channel) but used @ (a user prefix). A better, actionable message would be:

Cannot deliver a Channelz message to channel '@barnyard-friends': it is prefixed with @. Did you mean to pass it into 'users'? Or did you mean '#barnyard-friends'?

This eliminates the user's search space, saving time and preventing churn. For developers, the error must also be programmable. The book advocates for raising errors at the interface boundary—the API or UI layer—where you have full context about the user's intent. This allows you to repackage lower-level errors into something meaningful.

Shifting Left: Diagnose Early

A key product-minded principle is "shift left"—providing diagnostics as early as possible. This saves user time and system resources. The excerpt outlines four techniques:

- Static Validations: Cheap checks like format validation (e.g., postal code length, credit card checksums) done immediately on input.

- Validate Upfront: For multi-step workflows (like moving money), validate prerequisites before the main action to prevent partial failures.

- Let Them Test: Provide a high-fidelity fake or test mode. Stripe's test mode is a prime example, allowing developers to simulate errors like

card_declinedwith specific card numbers (e.g.,4000 0000 0000 9995for insufficient funds) without real transactions. - Request User Confirmations: Use heuristics to flag potentially dangerous or unusual input before execution. For example, a retry policy that would attempt 601 requests in 600 seconds could trigger a warning: "This exceeds our limit of 50. You may ignore this by adding

.ignore(Errors::RetryPolicySpamminess)." This is a middle ground between a hard error and a silent pass.

The Broader Impact

This excerpt is a microcosm of the book's approach: taking a seemingly mundane, often-overlooked aspect of engineering—error messages—and applying a product-thinking lens to it. The result is a framework that improves usability, reduces support burden, and creates stickier products.

For engineers looking to become more product-minded, this is a tangible skill to develop. Start by categorizing the errors in your own codebase. Ask: Who is the user of this error? What action do they need to take? Are you raising it at the right layer to provide full context?

As AI tools take over more routine coding, the engineer's role shifts towards specification and system design. Understanding how users (human and AI) interact with your system's diagnostics is a fundamental part of that shift. As Hoskins demonstrates, a well-designed error isn't a failure; it's a guided path back to success.

Related Links:

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion