In January 1917, British cryptanalysts intercepted Germany's explosive proposal to Mexico – but revealing it risked exposing their greatest intelligence coup. This is how Room 40's codebreakers pulled off history's most consequential deception.

The corridors of London's Admiralty Old Building echoed with shouts as Lieutenant Nigel De Grey dodged trolleys and disapproving superiors. Clutched in his hand was a scrap of paper that could break the Western Front stalemate: Germany's secret proposal for Mexico to invade the United States. But this breakthrough presented an impossible dilemma – how could Britain expose the Zimmermann Telegram without revealing they'd been reading America's diplomatic mail?

The Unlikely Codebreakers De Grey, a publishing-house alumnus nicknamed "Dormouse" for his shyness, represented Room 40's unconventional talent pool. Recruited for his German fluency and puzzle-solving obsession, he worked alongside classics scholar Alfred "Dilly" Knox. Their workspace was a converted backroom where the Admiralty gathered radio intercepts and cipher texts, exploiting Germany's compromised communications after Britain severed transatlantic cables in 1914.

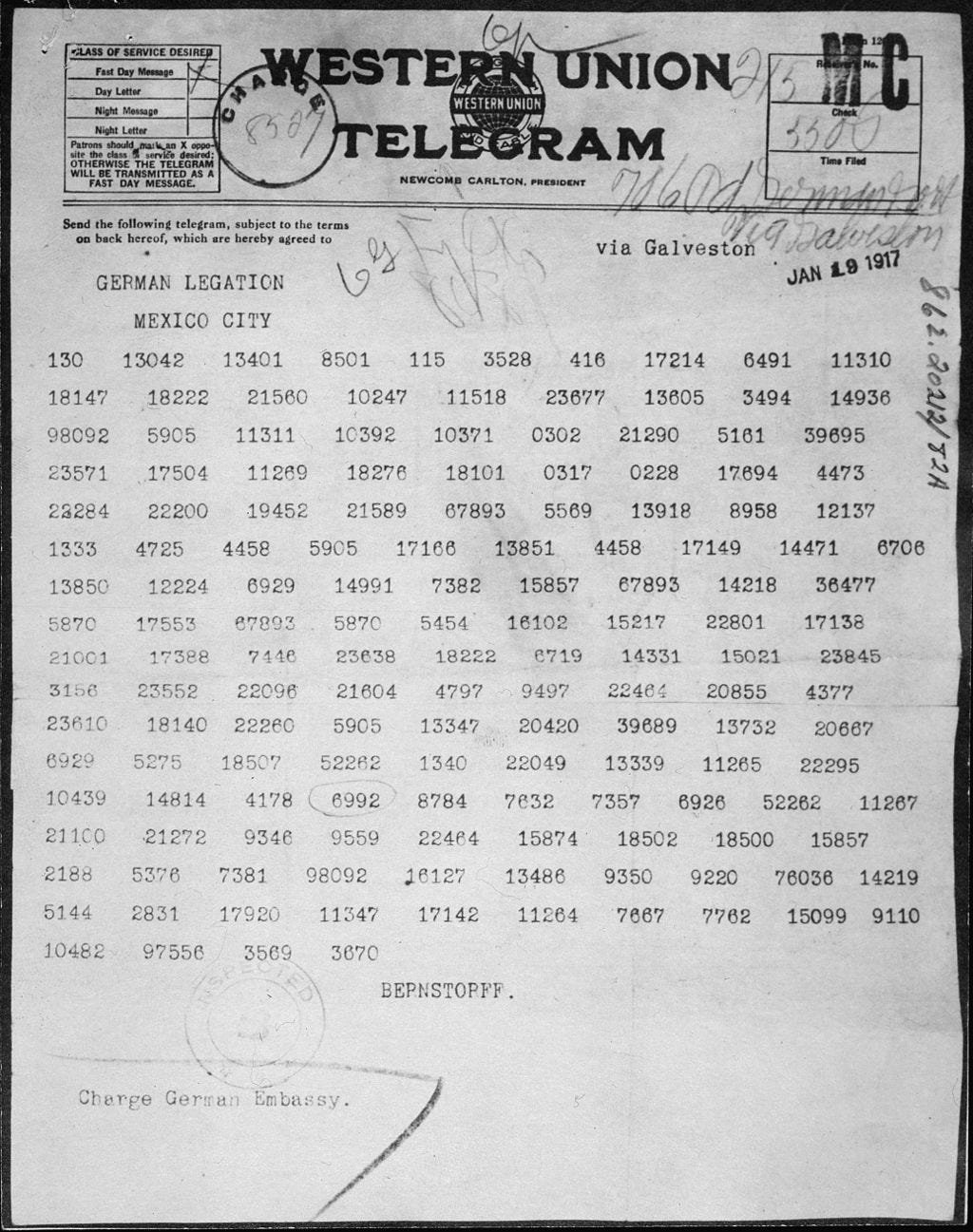

Germany's Fatal Mistake When neutral America offered Germany use of its diplomatic cable via Denmark, Berlin assumed immunity. They didn't foresee Captain Reginald "Blinker" Hall's Research Group – a covert unit within Room 40 tasked with monitoring neutral nations' traffic. On January 16, 1917, a low-priority German diplomatic message landed on Knox's desk. Recognizing patterns in the cipher, Knox worked through the night, later recruiting De Grey. By noon, they stared at Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann's explosive proposal:

"Make war together... Mexico is to reconquer lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona... ruthless employment of our submarines [will] compel England to make peace."

The Espionage Tightrope Hall recognized the telegram could drag America into the war – but exposing it would reveal Britain's access to U.S. diplomatic channels. The solution? Hall exploited a critical flaw: Zimmermann had routed the message through his Washington ambassador, who would decrypt and re-send it via Western Union's commercial cable to Mexico. Hall's team bribed a clerk in Mexico City's Western Union office to steal the resent version.

The Double Bluff When U.S. diplomat Edward Bell demanded proof in London, Hall presented the stolen Western Union copy. But Bell insisted on witnessing decryption – unaware Room 40 hadn't fully broken that cipher. De Grey improvised at the table, blending genuine decryptions with educated guesses while Hall maintained icy composure. "Several seconds of bloody sweat," De Grey recalled. "Then I bluffed." Bell, convinced he'd seen authentic codebreaking, declared it genuine.

The Aftermath Published on February 28, 1917, the telegram ignited American outrage. Coupled with Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare, it pushed the U.S. to declare war on April 5 – reshaping the conflict's outcome. Hall's deception held for decades: the official story credited a Mexican wiretap, concealing Room 40's penetration of U.S. channels. Knox later pioneered Britain's WWII codebreaking at Bletchley Park, while De Grey's only reprimand came for that frantic run through Admiralty corridors – a small price for history's most consequential sprint.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion