Before digital audio workstations and algorithmic composition software, there was the Triadex Muse — a rare 1972 device that turned zeroes and ones into melodies through pure electronic logic.

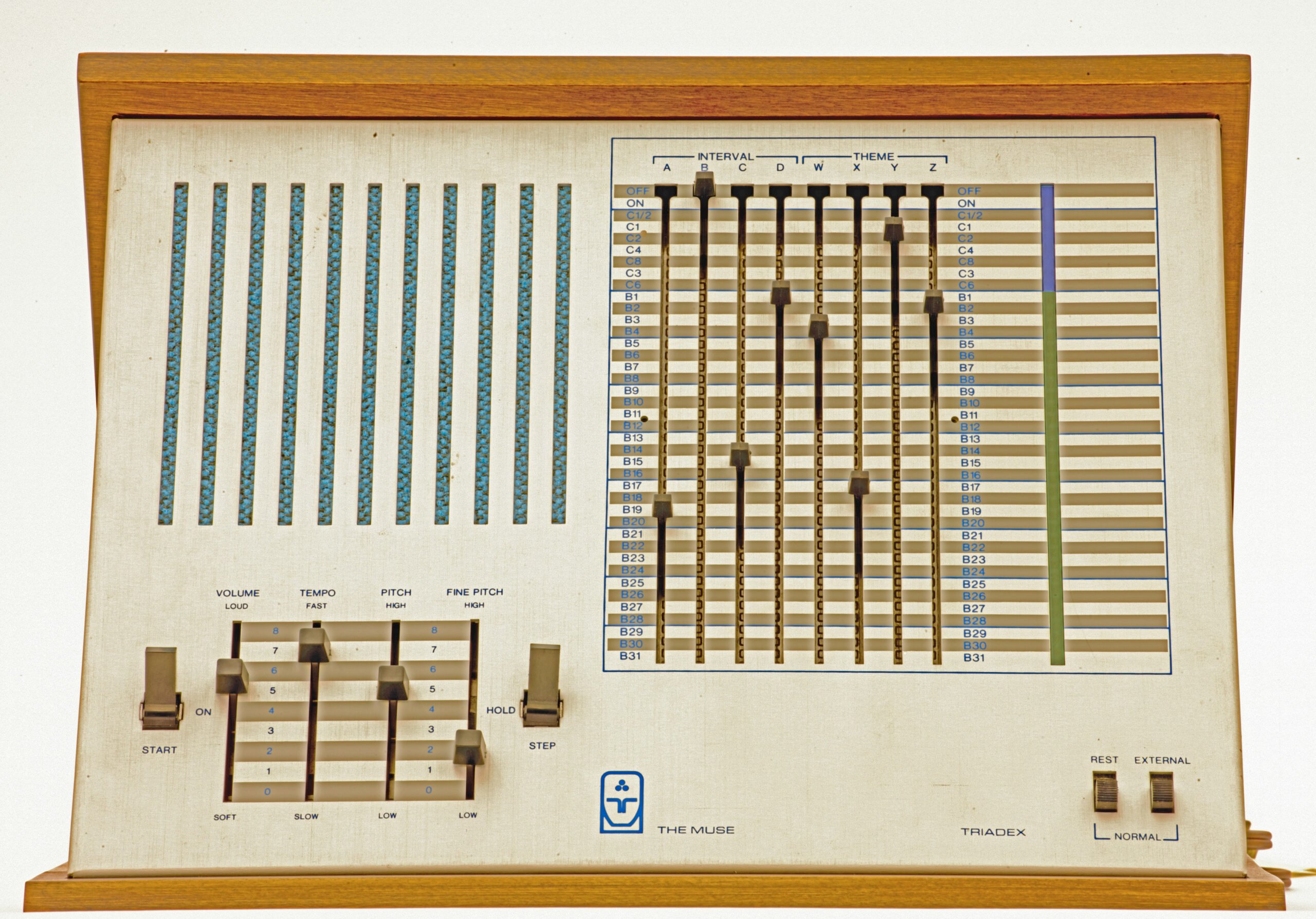

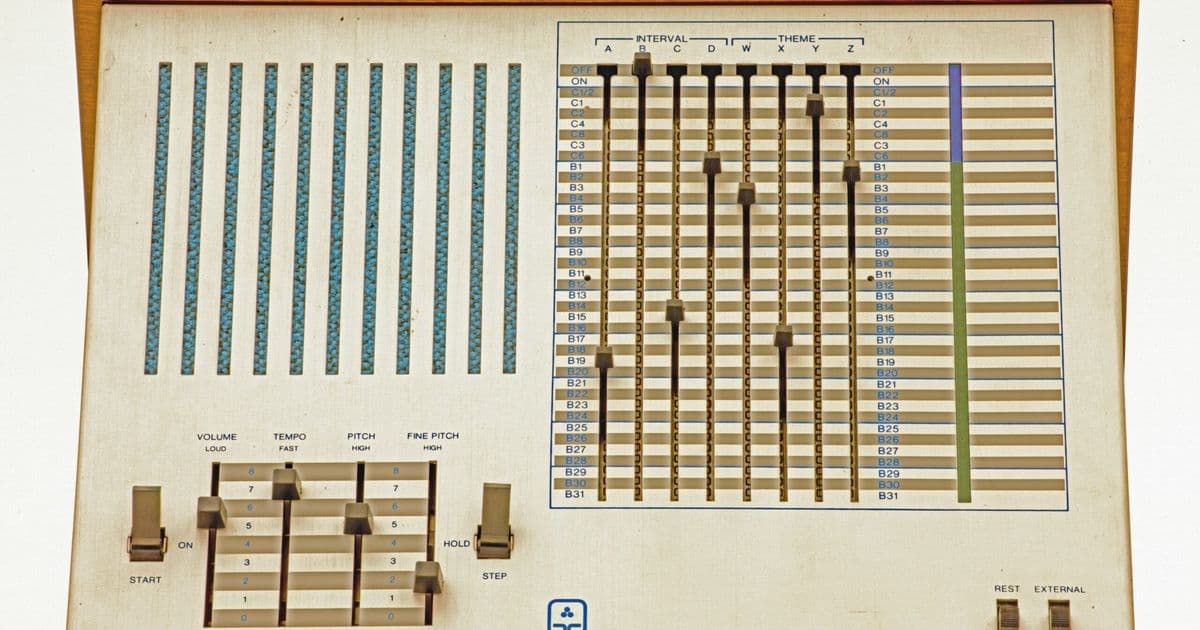

The Triadex Muse stands as one of the most unusual artifacts in electronic music history. Developed by Edward Fredkin and Marvin Minsky at MIT in 1969 and released commercially in the early 1970s, this wedge-shaped device with its wood panels and array of sliders looks more like a piece of stereo equipment than a musical instrument. With only 280-300 units ever produced, it represents a fascinating dead-end in the evolution of electronic music technology.

Unlike modern synthesizers with their familiar piano-style keyboards, the Muse offered no traditional musical interface. Instead, users manipulated a series of sliders to control its algorithmic composition system. There was no memory, no CPU, and no firmware—just integrated circuits and electricity working together to create music through pure binary logic.

The Muse's operation centered on a 40x8 matrix of zeroes and ones, evaluated at each tick of its internal clock. This wasn't random noise generation but a carefully designed system where each state could potentially change what happened next. The blinking blue and green lights weren't just for show—they displayed the complete binary state of the system in real-time, creating a visual representation of the music being generated.

At the heart of the Muse's musical capabilities were its INTERVAL controls. These four sliders selected notes from the major scale, with positions A, B, and C determining pitch while D added an octave. The system was deliberately limited—no flatted thirds, no minor scales, no way to play the blues. This restriction wasn't a limitation but a design choice that forced the Muse to work within specific musical parameters while still generating surprising variations.

The real magic happened in the B register, where pseudo-random sequencing created endless musical variations. Each of the four THEME sliders acted as a "tap," monitoring specific points in the binary matrix and sending that information to an XNOR logic gate. At every clock tick, this gate made decisions based on the binary inputs it received. If it got an even number of ones (including all zeroes), it sent a one to B1; if the number was odd, it sent a zero.

This created what's known as a Linear Shift Register—an ever-evolving sequence where new bits were constantly being added while old ones fell away. The 31-bit B register meant the Muse could generate patterns that would take an extraordinarily long time to repeat, creating the illusion of endless musical variation while still operating within strict logical rules.

Marvin Minsky, one of the Muse's creators, understood the fundamental challenge of algorithmic composition. In his 1981 paper "Music, Mind, and Meaning," he wrote that the challenge of composing music is that "Whatever the intent, control is required or novelty will turn to nonsense." This philosophy was hardwired into the Muse's design. While its melodies could sound familiar or strange, they always maintained an underlying logic that our brains could recognize as patterns, even when the specific sequence was unpredictable.

The Muse's influence extends far beyond its limited production run. Modern algorithmic composition tools and generative music systems owe a debt to this pioneering device. Artists like Autechre, pioneers of generative electronic music, work with similar principles—using complex calculations to create music that sounds organic and surprising while remaining fundamentally non-random.

Despite its innovative approach, the Muse was ultimately a technological cul-de-sac. It couldn't connect to other synthesizers, lacked MIDI compatibility, and had no way to save or recall settings. Its entire ecosystem consisted of the device itself, an external speaker, and an optional light unit that created psychedelic visual effects synchronized to the music.

Today, the Triadex Muse represents a fascinating moment when computer science and music composition collided in a uniquely physical form. It reminds us that sometimes the most innovative musical instruments aren't the ones that try to replicate existing ones, but those that create entirely new ways of thinking about sound and structure. In an era of digital audio workstations and AI music generators, the Muse stands as a testament to the power of simple rules to create complex, engaging musical experiences.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion