This article explores the technical process of configuring an Arch Linux system with an encrypted root partition to accept remote SSH connections during the early boot process, before the disk is unlocked. It details the challenges of networking in initramfs, integrating Tailscale and a minimal SSH server, and securing the setup against unauthorized access.

The scenario is a familiar one for the traveling developer: a home desktop, encrypted for security, that needs to be accessible remotely. The problem arises when the system loses power and reboots, requiring a decryption password to be typed locally. This creates a barrier to remote access. The solution proposed is to embed networking and remote access capabilities directly into the initramfs—the minimal operating system that runs from memory before the main OS and its encrypted storage are mounted. This allows the machine to be unlocked from anywhere in the world, provided it has network connectivity.

The Boot Process and Initramfs

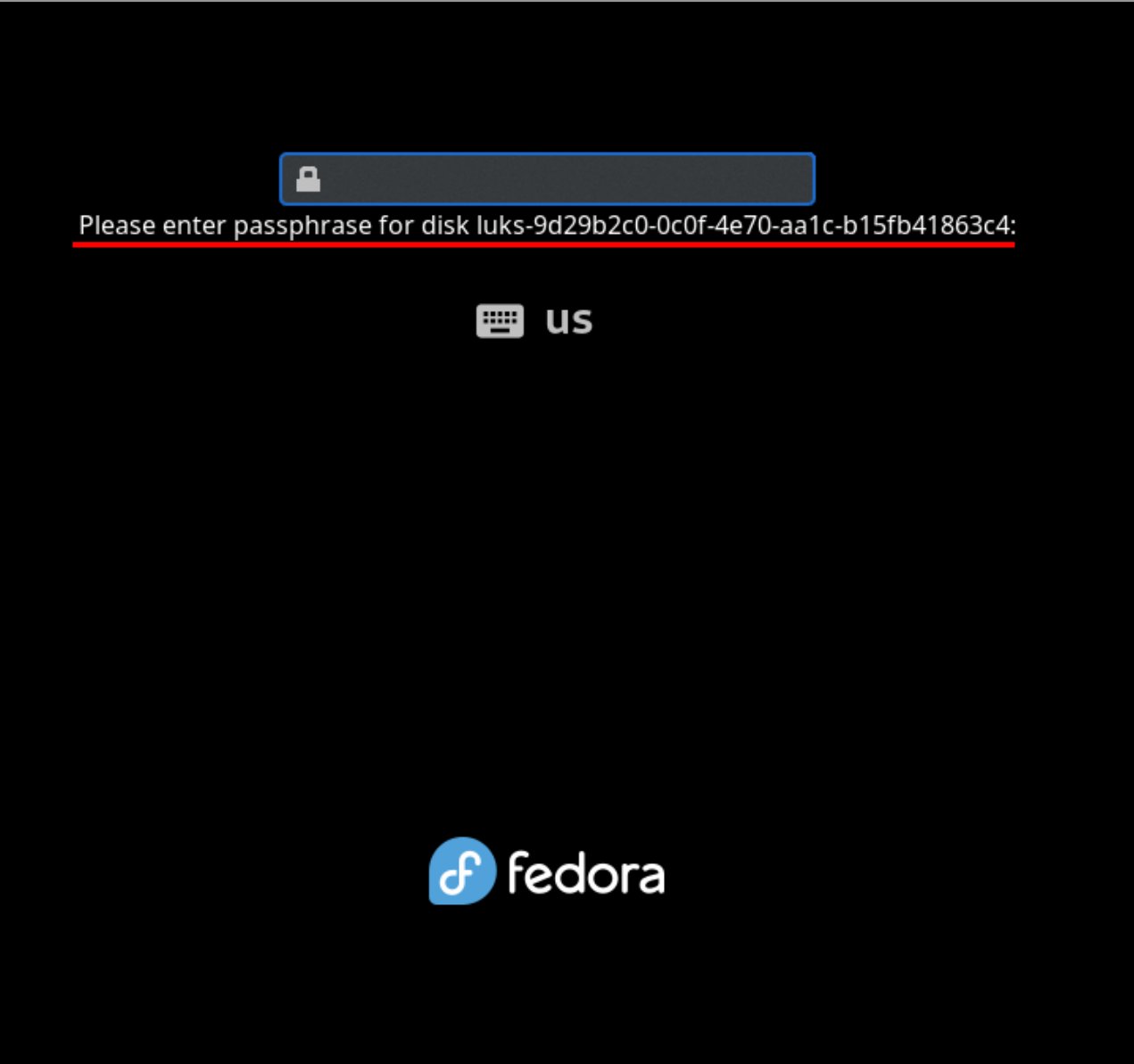

To understand the challenge, one must first understand the Linux boot process. When a system with an encrypted root partition starts, the initial boot loader loads a compressed archive called the initramfs (initial RAM filesystem) into memory. This archive contains a small, functional operating system—often including a copy of systemd—that runs entirely from RAM. Its primary job is to prepare the environment needed to mount the real root filesystem, which typically involves prompting for a decryption passphrase. Once the passphrase is entered and the encrypted volume is unlocked, the initramfs hands control over to the main operating system.

This initramfs environment is not a bare-bones script; it's a full, albeit minimal, Linux system with its own PID 1 (init) and service management. This is why tools like systemd-analyze can report on early boot performance—they are reading metrics from the systemd instance running within the initramfs. This fact is the key to the entire plan: if the initramfs is a functional Linux environment, it should be possible to install and run services within it, such as a network stack and an SSH server.

The Technical Architecture

The goal is to modify the initramfs to include three critical components:

- Networking: The system must establish a network connection immediately upon boot, before the disk is decrypted. This is the most fundamental requirement.

- Tailscale: To ensure reliable connectivity regardless of dynamic IP changes, a VPN overlay network like Tailscale is essential. It provides a stable, mesh-networked IP address for the machine.

- SSH Server: A minimal SSH daemon is needed to accept incoming connections and present the decryption prompt.

Networking in Initramfs

Configuring networking in the initramfs is non-trivial. The main OS typically relies on udev and NetworkManager to manage interfaces, but these are not present in the early boot environment. The solution involves using systemd's own network management capabilities. On Arch Linux, the mkinitcpio-systemd-extras package provides hooks for this purpose. Specifically, the sd-network hook can be configured to set up a DHCP client on a specific network interface. Since predictable network interface names (like enp0s3) are not assigned until later in the boot process, the configuration must target a generic interface type, such as ether (Ethernet). A configuration file like /etc/systemd/network-initramfs/10-wired.network can be created to match Ethernet interfaces and request a DHCP lease.

Integrating Tailscale

Running Tailscale within the initramfs presents unique challenges. Tailscale requires persistent state, such as machine keys and authentication secrets. In a standard system, this state is stored on the disk. In the initramfs, which runs from a temporary RAM filesystem, this state must be managed carefully. The mkinitcpio-tailscale hook is designed to handle this. It ensures that Tailscale's necessary components are included in the initramfs and that its state is persisted across reboots, likely by storing it in a location that is preserved (e.g., on the unencrypted /boot partition or via a separate mechanism).

A critical security consideration arises: the Tailscale keys stored in the initramfs are, by necessity, unencrypted. If an attacker gains physical access to the machine, they could potentially extract these keys. To mitigate this, Tailscale's Access Control Lists (ACLs) are used to create a strict policy. The machine running in initramfs is given a unique tag (e.g., tag:initrd). The ACL policy is then configured to deny all outgoing connections from this tagged machine, allowing it only to accept incoming SSH connections from authorized users. This limits the attack surface significantly.

The SSH Server and Security Hardening

The final piece is the SSH server. The sd-dropbear hook from mkinitcpio-systemd-extras integrates the lightweight Dropbear SSH daemon into the initramfs. However, exposing an SSH server in the initramfs is a high-risk proposition. If compromised, an attacker could potentially manipulate the boot process or gain early system access.

To harden this, the configuration is locked down aggressively. The SD_DROPBEAR_COMMAND variable is set to systemd-tty-ask-password-agent. This forces any SSH session to immediately execute the systemd password agent, which is the program that prompts for the disk decryption passphrase. It does not provide a shell or any other command execution capability. Furthermore, only public keys from trusted users (stored in /root/.ssh/authorized_keys) are authorized for access. This creates a tightly controlled conduit: the only possible action via SSH is to enter the decryption password.

Implementation on Arch Linux

The process on Arch Linux involves several specific steps:

- Install Packages: Install

dropbear,mkinitcpio-systemd-extras, andmkinitcpio-tailscale. - Configure Hooks: Modify

/etc/mkinitcpio.confto include the necessary hooks in the correct order:sd-network,tailscale, andsd-dropbearmust be added beforesd-encryptandfilesystems. - Set Up Tailscale: Run

setup-initcpio-tailscaleto generate the necessary keys. In the Tailscale admin console, tag the new device withtag:initrdand disable key expiry to prevent the connection from breaking after 90 days. - Configure Dropbear: Set

SD_DROPBEAR_COMMANDto restrict the SSH session to the password agent only. Generate a host key for Dropbear if one doesn't exist. - Configure Networking: Create a systemd-networkd configuration file for the initramfs that matches Ethernet interfaces and enables DHCP.

- Adjust Boot Parameters: For systems using systemd-boot, the boot entry may need a parameter like

x-systemd.device-timeout=0to prevent the system from giving up on the decryption prompt. - Rebuild Initramfs: Run

mkinitcpio -Pto regenerate the initramfs images for all installed kernels.

After a reboot, the machine will appear in the Tailscale network as a new device (e.g., hostname-initrd). An authorized user can then SSH into this device, which will immediately present the disk decryption prompt. Once the correct passphrase is entered, the initramfs completes its job, unlocks the disk, and boots into the main operating system.

Implications and Trade-offs

This setup demonstrates a powerful principle: the boot process itself can be treated as a programmable environment. By leveraging the flexibility of initramfs and systemd, it's possible to extend functionality far beyond its original design. However, this power comes with significant trade-offs.

Security: The primary concern is the exposure of the decryption prompt over a network. While mitigated by Tailscale ACLs and SSH key authentication, the attack surface is undeniably larger than a purely local setup. Physical security becomes even more critical, as an attacker with console access could potentially interfere with the boot process. The unencrypted Tailscale keys in the initramfs are a persistent vulnerability.

Reliability: The setup introduces multiple points of failure. Networking must come up correctly in the initramfs. Tailscale must authenticate and establish a connection. The SSH server must start and accept connections. Any failure in this chain could leave the machine inaccessible remotely, requiring physical intervention.

Complexity: The configuration is complex and requires a deep understanding of the Linux boot process, systemd, and networking. It is not a one-size-fits-all solution and may require adjustments for different hardware or network environments (e.g., WiFi is notably more difficult).

Conclusion

Remotely unlocking an encrypted disk is a compelling use case that pushes the boundaries of system initialization. It transforms the initramfs from a simple helper into a networked service environment. While the technical hurdles are substantial, they are surmountable with the right tools and careful configuration. The solution exemplifies a broader trend in system administration: using software-defined networking and overlay systems to overcome the limitations of traditional hardware and boot processes. For those who travel frequently or manage headless servers, this approach offers a powerful way to maintain access and control, provided the inherent security risks are carefully managed. The key takeaway is that with sufficient technical insight and a willingness to extend system components into unconventional areas, many seemingly impossible problems become solvable.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion