Researchers at Sandia National Laboratories demonstrated that domain-specific AI agents can autonomously conduct and optimize scientific experiments, achieving a fourfold improvement in LED light steering over human-developed methods. The team used mature, non-LLM architectures to avoid hallucinations and conducted over 300 tests in just five hours, showcasing a practical path toward self-driving laboratories.

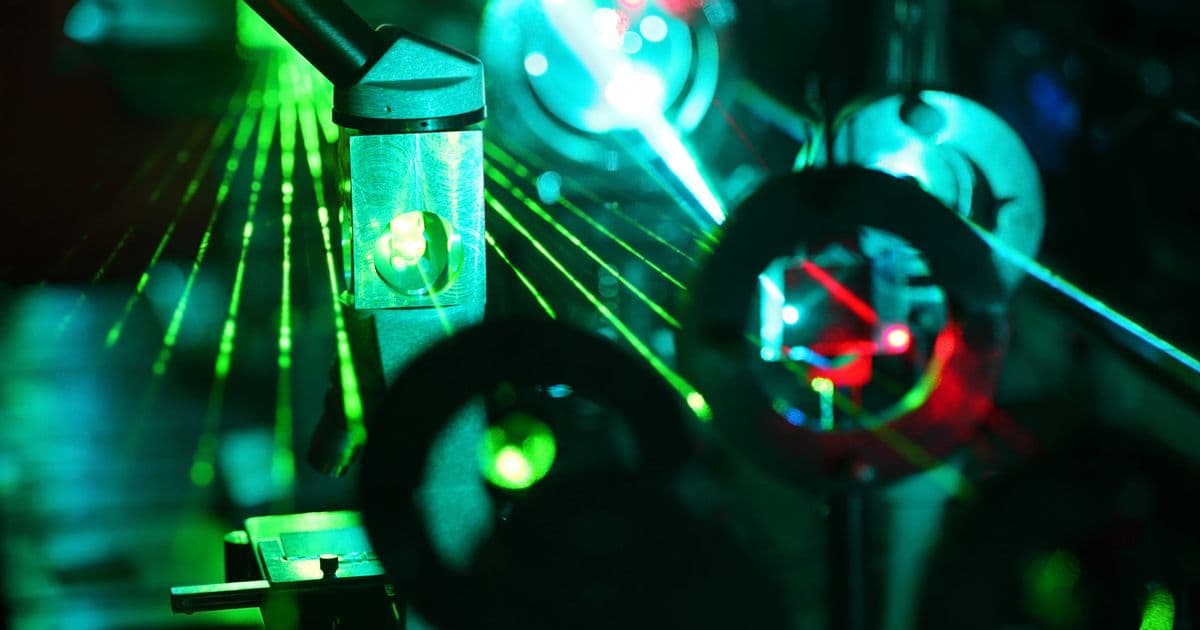

Scientists at the Department of Energy's Sandia National Laboratories have demonstrated a practical application for AI agents in experimental science, achieving a fourfold improvement in LED light steering results by letting three specialized AI assistants run experiments autonomously in their lab. The work, detailed in a paper published in Nature Communications, shows how domain-specific AI models can accelerate scientific discovery without relying on large language models or massive computational resources.

The research team, led by Prasad Iyer and Saaketh Desai, was working to develop cheap, power-efficient LEDs as potential replacements for lasers in applications ranging from autonomous vehicles to holographic projectors. The core challenge was finding the optimal combination of parameters to steer LED light in a desired manner—a process that could take years of manual experimentation. To accelerate this, the researchers developed a trio of AI lab assistants that operated in a closed-loop system, conducting and refining experiments without human intervention.

A Self-Driving Lab in Practice

Unlike many AI agent projects that rely on API calls to third-party models, Sandia's team built custom, domain-specific models using well-established machine-learning algorithms. "We didn't do any LLMs. There is significant interest in that. There are lots of people trying those ideas out, but I think they're still in the exploratory phase," Desai explained. Instead, they opted for a variational autoencoder (VAE), a generative model first introduced in 2013, to pre-process the lab's data sets.

The VAE architecture, commonly used for image generation before diffusion models emerged in 2015, was chosen for its maturity and reliability. By sticking with proven architectures tailored to their specific task, the team avoided the hallucination problems that plague many generative AI systems. "Hallucinations were not that big a concern here because we build a generative model that is tailored for this very specific task," Desai noted.

The system operated through three interconnected models:

Data Pre-processing Model: A VAE that processed the lab's existing data sets to identify patterns and prepare inputs for experimentation.

Active Learning Model: A Bayesian optimization algorithm connected directly to optical equipment. This model generated experiments, executed them, and analyzed the results in real time.

Verification Model: A simple feed-forward neural network that acted as a fact-checker, devising formulas for the generated data to verify results and ensure scientific validity.

This closed-loop system allowed the models to continuously refine experiments, moving beyond merely identifying optimal parameters to understanding why specific configurations worked. "The real science is in uncovering why that particular configuration works at all," the researchers noted.

Efficiency and Practicality

Remarkably, the entire system ran on modest hardware: a Lambda Labs workstation equipped with three RTX A6000 graphics cards. This stands in stark contrast to typical AI training runs that require hundreds of thousands of GPUs. The team's approach demonstrates that scientific AI doesn't necessarily require massive computational resources when the models are appropriately scoped and optimized.

In just five hours, the AI agents conducted over 300 experiments, not only achieving a fourfold improvement in LED beam steering but also surfacing novel approaches the researchers hadn't previously considered. This represents a significant acceleration from the years of experimentation originally anticipated.

Implications for Scientific Research

The Sandia experiment builds on a 2023 paper by Iyer and his team that first demonstrated methods for steering LED light. The new work shows how AI agents can systematically explore parameter spaces that would be impractical for human researchers to navigate manually. Desai believes the underlying approach has applications beyond optics, potentially extending to materials design for alloys or printable electronics.

However, the researchers emphasize that successful implementation requires careful consideration of both hardware and methodology. "There's progress and development there, but there's still a long way to go in terms of making sure that the tools that are in the lab, the physical tools, are able to interact with these models," Desai explained. "If you're using a piece of equipment from 1975 you're already in a tough place to start."

The team also cautions against over-reliance on more complex AI architectures without proper validation. "If you're going into more advanced architectures and machine learning—transformer based LLM and what not—I would say my advice is to be really skeptical of what it gives you," Desai advised.

Toward Self-Driving Laboratories

The Sandia research represents one of the leading examples of what researchers call "self-driving laboratories"—fully automated systems that can design, execute, and analyze experiments without human intervention. As Iyer stated in a blog post, "We are one of the leading examples of how a self-driving lab could be set up to aid and augment human knowledge."

This approach addresses a fundamental bottleneck in scientific research: the time and labor required for experimental iteration. By automating the experimental cycle, researchers can explore more hypotheses, test more parameters, and potentially discover solutions that might elude traditional methods.

The work also highlights a pragmatic path for AI in science. Rather than chasing the latest large language models or requiring massive computational resources, the Sandia team achieved significant results using mature, purpose-built models on modest hardware. This suggests that the future of AI in scientific research may lie not in general-purpose models, but in specialized systems designed for specific experimental domains.

For other laboratories interested in implementing similar systems, the key takeaway is the importance of integration between physical equipment and AI models. The success of the Sandia experiment depended on tight coupling between the AI agents and the optical equipment, enabling real-time feedback and adjustment. As equipment becomes more digitally integrated and AI models become more accessible, the potential for self-driving laboratories to accelerate scientific discovery continues to grow.

The research demonstrates that AI agents, when properly designed and implemented, can serve as powerful tools for scientific exploration—achieving not just incremental improvements but novel insights that expand human understanding. In an era where AI is often associated with content generation or task automation, this work provides a compelling example of AI as a partner in scientific discovery.

Read the full paper in Nature Communications for detailed methodology and experimental results.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion